M04-OrigLife

Origin of Life on Earth

Fresh clues hint at how the first living organisms arose from inanimate matter

KEY CONCEPTS

<>

Researchers have found a way that the genetic molecule RNA could have

formed from chemicals present on the early earth.

<> Other studies have supported the hypothesis that primitive cells

containing molecules similar to RNA could assemble spontaneously, reproduce and

evolve, giving rise to all life.

<>

Scientists are now aiming at creating fully self-replicating artificial

organisms in the laboratory-essentially giving life a second start to

understand how it could have started the first time. -The Editors

The Authors

Alonso

Ricardo, who was born in Cali, Colombia, is a research associate at the Howard

Hughes Medical Institute at Harvard University. He has a long-standing interest

in the origin of life and is now studying self-replicating chemical systems.

Jack

w. Szostak is professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts

General Hospital. His interest in the laboratory construction of biological

structures as a means of testing our understanding of how biology works dates

back to the artificial chromosomes he described in the November 1987 Scientific

American.

John

Sutherland of the University of Manchester in England and his collaborators

solved a long-standing question in prebiotic chemistry this past May by

demonstrating that nucleotides can form from spontaneous chemical reactions. He

appears above (second from left) with members of his lab.

Every living cell, even the simplest

bacterium, teems with molecular contraptions that would be the envy of any

nanotechnologist. As they incessantly shake or spin or crawl around the cell,

these machines cut, paste and copy genetic molecules, shuttle nutrients around

or turn them into energy, build and repair cellular membranes, relay

mechanical, chemical or electrical messages the list goes on and on, and new

discoveries add to it all the time. It is virtually impossible to imagine how a

cell's machines, which are mostly protein-based catalysts called enzymes, could

have formed spontaneously as life first arose from nonliving matter around 3.1

billion years ago. To be sure, under the right conditions some building blocks

of proteins, the amino acids, form easily from simpler chemicals, as Stanley L.

Miller and Harold C. Urey of the University of Chicago discovered in pioneering

experiments in the 1950s. But going from there to proteins and enzymes is a

different matter.

A cell's protein-making process

involves complex enzymes pulling apart the strands of DNA's double helix to

extract the information contained in genes (the blueprints for the proteins)

and translate it into the finished product. Thus, explaining how life began

entails a serious paradox: it seems that it takes proteins-as well as the

information now stored in DNA-to make proteins.

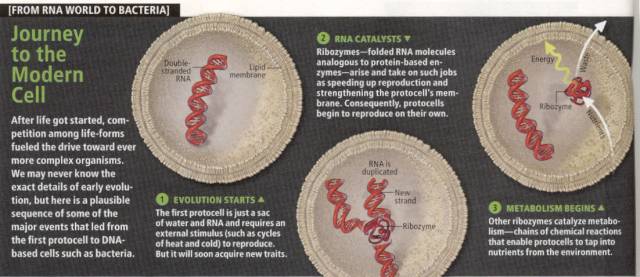

On the other hand, the paradox would

disappear if the first organisms did not require proteins at all. Recent

experiments suggest it would have been possible for genetic molecules similar

to DNA or to its close relative RNA to form spontaneously. And because these

molecules can curl up in different shapes and act as rudimentary catalysts,

they may have become able to copy themselves-to reproduce-with out the need for

proteins. The earliest forms of life could have been simple membranes made. of

fatty acids-also structures known to form spontaneously-that enveloped water

and these self-replicating genetic molecules. The genetic material would encode

the traits that each generation handed down to the next, just as DNA does in

all things that are alive today. Fortuitous mutations, appearing at random in

the copying process, would then propel evolution, enabling these early cells to

adapt to their environment, to compete with one another, and eventually to turn

into the life forms we know.

The actual nature of the first

organisms and the exact circumstances of the origin of life may be forever lost

to science. But research can at least help us understand what is possible. The

ultimate challenge is to construct an artificial organism that can reproduce

and evolve. Creating life anew will certainly help us understand how life can

start, how likely it is that it exists on other worlds and, ultimately, what

life is.

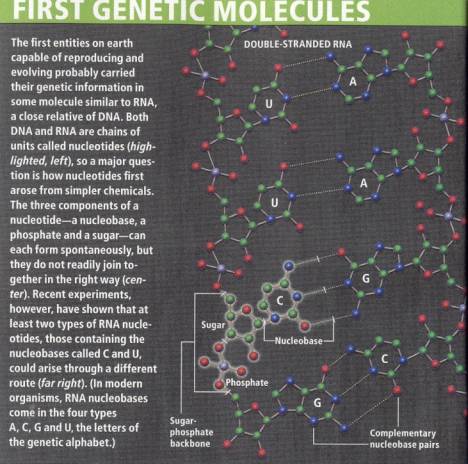

One of the most difficult and interesting mysteries surrounding the origin of life is exactly how the genetic material could have formed starting from simpler molecules present on the early earth. Judging from the roles that RNA has in modern cells, it seems likely that RNA appeared before DNA. When modern cells make proteins, they first copy genes from DNA into RNA and then use the RNA as a blueprint to make proteins. This last stage could have existed independently at first. Later on, DNA could have appeared as a more permanent form of storage, thanks to its superior chemical stability.

Got to Start Somewhere

Investigators have one more reason

for thinking that RNA came before DNA. The RNA versions of enzymes, called

ribozymes, also serve a pivotal role in modern cells. The structures that

translate RNA into proteins are hybrid RNA protein machines, and it is the RNA

in them that does the catalytic work. Thus, each of our cells appears to carry

in its ribosomes "fossil" evidence of a primordial RNA world.

Much research, therefore, has

focused on understanding the possible origin of RNA. Genetic molecules such as

DNA and RNA are polymers {strings of smaller molecules) made of building blocks

called nucleotides. In turn, nucleotides have three distinct components: a sugar,

a phosphate and a nucleobase. NucJeobases come in four types and constitute the

alphabet in which the polymer encodes information. In a DNA nucleotide the

nucleobase can be A, G, C or T, standing for the molecules adenine, guanine,

cytosine or thymine; in the RNA alphabet the letter U, for uracil, replaces the

T [see box above]. The nucleobases are nitrogen-rich compounds that bind to one

another according to a simple rule; thus, A pairs with U {or T), andG pairs

with C. Such base pairs form the rungs of DNA's twisted ladder-the familiar

double helix-and their exclusive pairings are crucial for faithfully copying

the information so a cell can reproduce. Meanwhile the phosphate and sugar

molecules form the backbone of each strand of DNA or RNA.

Nucleobases can assemble

spontaneously, in a series of steps, from cyanide, acetylene and water-simple

molecules that were certainly present in the primordial mix of chemicals.

Sugars are also easy to assemble from simple starting materials. It has been

known for well over 100 years that mixtures of many types of sugar molecules

can be obtained by warming an alkaline solution of formaldehyde, which also

would have been available on the young planet.

The

problem, however, is how to obtain the "right" kind of sugar-ribose,

in the case of RNA-to make nucleotides. Ribose, along with three closely

related sugars, can form from the reaction of two simpler sugars that contain

two and three carbon atoms, respectively. Ribose's ability to form in that way

does not solve the problem of how it became abundant on the early earth,

however, because it turns out that ribose is unstable and rapidly breaks down

in an even mildly alkaline solution. In the past, this observation has led many

researchers to conclude that the first genetic molecules could not have

contained ribose. But one of us (Ricardo) and others have discovered ways in

which ribose could have been stabilized.

Some Assembly

Required

The phosphate part of nucleotides presents another intriguing puzzle. Phosphorus-the central element of the phosphate group-is abundant in the earth's crust but mostly in minerals that do not dissolve readily in water, where life presumably originated. So it is not obvious how phosphates would have gotten into the prebiotic mix. The high temperatures of volcanic vents can convert phosphate-containing minerals to soluble forms of phosphate, but the amounts released, at least near modern volcanoes, are small. A completely different potential source of phos-

phorus

compounds is schreibersite, a mineral commonly found in certain meteors.

In 2005 Matthew Pasek and Dante

Lauretta of the University of Arizona discovered that the corrosion of

Schreiber site in water releases its phosphorus component. This pathway seems

promising because it releases phosphorus in a form that is both much more

soluble in water than phosphate and much more reactive with organic

(carbon-based) compounds.

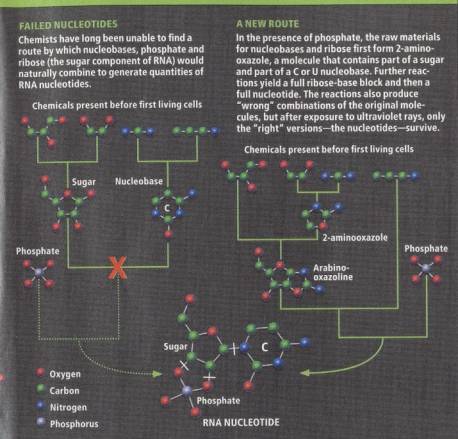

Given that we have at least an

outline of potential pathways leading to the nucleobases, sugars and phosphate,

the next logical step would be to properly connect these components. This step,

however, is the one that has caused the most intense frustration in prebiotic

chemistry research for the past several decades. Simply mixing the three

components in water does not lead to the spontaneous formation of a

nucleotide-largely because each joining reaction also involves the release of a

water molecule, which does not often occur spontaneously in a watery solution.

For the needed chemical bonds to form, energy must be supplied, for example, by

adding energy-rich compounds that aid in the reaction. Many such compounds may

have existed on the early earth. In the laboratory, however, reactions powered

by such molecules have proved to be inefficient at best and in most cases completely

unsuccessful.

This spring-to the field's great excitement John Sutherland and his co-workers at the University of Manchester in England announced that they found a much more plausible way that nucleotides could have formed, which also side-steps the issue of ribose's instability. These creative chemists abandoned the tradition of attempting to make nucleotides by joining a nucleobase, sugar and phosphate. Their approach relies on the same simple starting materials employed previously, such as derivatives of cyanide, acetylene and formaldehyde. But instead of forming nucleobase and ribose separately and then trying to join them, the team mixed the starting ingredients together, along with phosphate. A complex web of reactions-with phosphate acting as a crucial catalyst at several steps along the way-produced a small molecule called 2-aminooxazole, which can be viewed as a fragment of a sugar joined to a piece of a nucleobase [see box above].

WHAT IS LIFE?

Scientists have long struggled to define "life" in a way that is broad enough to encompass forms not yet discovered. Here are some of the many proposed definitions.

1. Physicist Erwin Schrodinger suggested

that a defining property of living systems is that they self-assemble against

nature's tendency toward disorder. or entropy.

2. Chemist Gerald Joyce's "working

definition," adopted by NASA, is that life is "a self-sustaining

chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution."

3. In the "cybernetic

definition" by Bernard Korzeniewski, life is a network of feedback

mechanisms.

A crucial feature of this small,

stable molecule is that it is very volatile. Perhaps small amounts of

2-aminooxazole formed together with a mixture of other chemicals in a pond on

the early earth; once the water evaporated, the 2-aminooxazole vaporized, only

to condense elsewhere, in a purified form. There it would accumulate as a

reservoir of material, ready for further chemical reactions that would form a

full sugar and nucleobase attached to each other.

Another important and satisfying

aspect of this chain of reactions is that some of the early stage by-products

facilitate transformations at later stages in of the process. Elegan~ as it is,

,the pathway does not generate exclusively the "correct" nucleotides:

in some cases, the sugar and nucleobase are not joined in the proper spatial

arrangement. But amazingly, exposure to ultraviolet light-intense solar uv rays

hit shallow waters on the early earth-destroys the "incorrect"

nucleotides and leaves behind the "correct" ones. The end result is a

remarkably clean route to the C and U nucleotides. Of course, we still need a route to G and A, so challenges

remain. But the work by Sutherland's team is a major step toward explaining how

a molecule as complex as RNA could have formed on the early earth.

ALTERNATIVES

TO "RNA FIRST"

PNA FIRST: Peptide nucleic acid is a

molecule with nucleobases attached to a proteinlike backbone. Because PNA is

simpler and chemically more stable than RNA, some researchers believe it could

have been the genetic polymer of the first life-for.ms on earth.

METABOLISM FIRST: Difficulties in

explaining how RNA formed from inanimate matter have led some researchers to

theorize that life first appeared as networks of catalysts processing energy.

PANSPERMIA: Because "only" a few

hundred million years divide the formation of the earth and the appearance of

the first forms of life, some scientists have suggested that the very first

organisms on earth may have been visitors from other worlds.

Some Warm, Little Vial

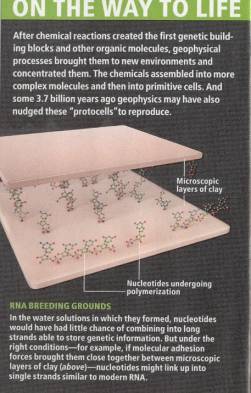

Once we have nucleotides, the final

step in the formation of an RNA molecule is polymerization: the sugar of one

nucleotide forms a chemical bond with the phosphate of the next, so that

nucleotides string themselves together into a chain. Once again, in water the

bonds do not form spontaneously and instead require some external energy. By

adding various chemicals to a solution of chemically reactive versions of the

nucleotides, researchers have been able to produce short chains of RNA, two to

40 nucleotides long. In the late 1990s Jim Ferris and his coworkers at the

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute showed that clay minerals enhance the process,

producing chains of up to 50 or so nucleotides. (A typical gene today is

thousands to millions of nucleotides long.) The minerals' intrinsic ability to

bind nucleotides brings reactive molecules close together, thereby facilitating

the formation of bonds between them [see box above].

The discovery reinforced the

suggestion by some researchers that life may have started on mineral surfaces,

perhaps in clay-rich muds at the bottom of pools of water formed by hot springs

, [see "Life's Rocky Start," by Robert M. Hazen;

SCIENTIFIC

AMERICAN, Apri12001].

Certainly finding out how genetic

polymers first arose would not by itself solve the problem of the origin of

life. To be "alive," organisms must be able to go forth and

multiply-a process that includes copying genetic information. In modern cells

enzymes, which are protein-based, carry out this copying function.

But genetic polymers, if they are

made of the right sequences of nucleotides, can fold into complex shapes and

can catalyze chemical reactions, just as today's enzymes do. Hence, it seems

plausible that RNA in the very first organisms could have directed its own replication.

This notion has inspired several experiments, both at our lab and at David

Bartel's lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in which we

"evolved" new ribozymes.

We started with trillions of random

RNA sequences. Then we selected the ones that had catalytic properties, and we

made copies of those. At each round of

copying some of the new RNA strands underwent mutations that turned them into

more efficient catalysts, and once again we singled those out for the next

round of copying. By this directed evolution we were able to produce ribozymes

that can catalyze the copying of relatively short strands of other RNAs,

although they fall far short of being able to copy polymers with their own

sequences into progeny RNAs.

Recently the principle of RNA

self-replication received a boost from Tracey Lincoln and Gerald Joyce of the

Scripps Research Institute, who evolved two RNA ribozymes, each of which could

make copies of the other by joining together two shorter RNA strands.

Unfortunately, success in the experiments required the presence of ~

preexisting RNA pieces that were far too long and complex to have accumulated

spontaneously. Still, the results suggest that RNA has the raw catalytic power

to catalyze its own replication.

Is there a simpler alternative? We

and others are now exploring chemical ways of copying genetic molecules without

the aid of catalysts. In recent experiments, we started with single,

"template" strands of DNA. (We used DNA because it is cheaper and

easier to work with, but we could just as well have used RNA.) We mixed the

templates in a solution containing isolated nucleotides to see if nucleotides

would bind to the template through complementary base pairing (A joining to T

and C to G) and then polymerize, thus forming a full double strand. This would

be the first step to full replication: once a double strand had formed,

separation of the strands would allow the complement to serve as a template for

copying the original strand. With

standard DNA or RNA, the process is exceedingly slow. But small changes to the

chemical structure of the sugar component-changing one oxygen-hydrogen pair to

an amino group (made of nitrogen and hydrogen)-made the polymerization hundreds

of times faster, so that complementary strands formed in hours instead of

weeks. The new polymer behaved much like classic RNA despite having

nitrogen-phosphorus bonds instead of the normal oxygen-phosphorus bonds.

Lipid Membranes self-assemble from fatty acid molecules dissolved in water. The membranes start out spherical and then grow filaments by absorbing new fatty acids (micrograph below). They become long, thin tubes and break up into many smaller spheres. The first protocells may have divided this way.

Life,

Redux

Scientists who study the origin of life hope

to build a self-replicating organism from entirely artificial ingredients. The

biggest challenge is to find a genetic molecule capable of copying itself

autonomously. The authors and their collaborators are designing and

synthesizing chemically modified versions of RNA and DNA in the search for this

elusive property. RNA itself is probably not the solution: its double strands,

unless they are very short, do not easily separate to become ready for

replication.

Boundary Issues

If we assume for the moment that the

gaps in our understanding of the chemistry of life's origin will someday be

filled, we can begin to consider how molecules might have interacted to

assemble into the first cell-like structures, or "protocells."

The membranes that envelop all

modern cells consist primarily of a lipid bilayer: a double sheet of such oily

molecules as phospholipids and cholesterol. Membranes keep a cell's components

physically together and form a barrier to the uncontrolled passage of large

molecules. Sophisticated proteins embedded in the membrane act as gatekeepers

and pump molecules in and out of the cell, while other proteins assist in the

construction and repair of the membrane. How on earth could a rudimentary

protocell, lacking protein machinery, carry out these tasks?

Primitive membranes were probably made of simpler molecules, such as fatty acids (which are one component of the more complex phospholipids). Studies in the late 1970s showed that membranes could indeed assemble spontaneously from plain fatty acids, but the general feeling was that these membranes would still pose a formidable barrier to the entry of nucleotides and other complex nutrients into the cell. This notion suggested that cellular metabolism had to develop first, so that cells could synthesize nucleotides for themselves. Work in our lab has shown, however, that molecules as large as nucleotides can in fact easily slip across membranes as long as both nucleotides and membranes are simpler, more "primitive" versions of their modern counterparts.

This finding allowed us to carry out

a simple experiment modeling the ability of a protocell to copy its genetic

information using environmentally supplied nutrients. We prepared fatty acid-

based membrane vesicles containing a short piece of single-stranded DNA. As

before, the DNA was meant to serve as a template for a new strand. Next, we

exposed these vesicles to chemically reactive versions of nucleotides. Tht

nucleotides crossed the membrane spon- taneously and, once inside the model protocell,

lined up on the DNA strand and reacted with one another to generate a

complementary strand. The experiment supports the idea that the first

protocells contained RNA (or something similar to it) and little else and

replicated their genetic material without enzymes.

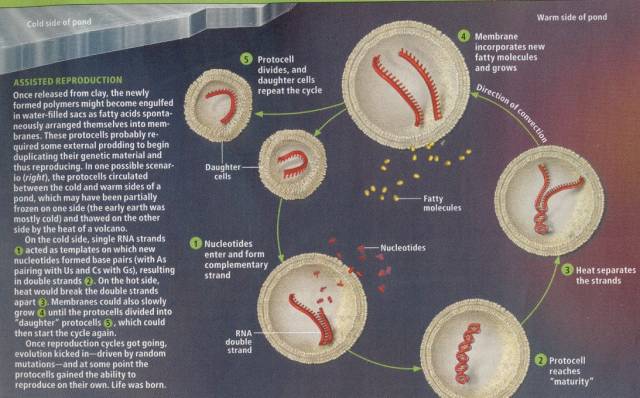

Let There Be Division

For protocells to start reproducing,

they would have had to be able to grow, duplicate their genetic contents and

divide into equivalent "daughter" cells. Experiments have shown that

primitive vesicles can grow in at least two distinct ways. In pioneering work

in the 1.990s, Pier Luigi Luisi and his colleagues at the Swiss Federal

Institute of Technology in Zurich added fresh fatty acids to the water

surrounding such vesicles. In response, the membranes incorporated the fatty

acids and grew in surface area. As water and dissolved substances slowly

entered the interior, the cell's volume also increased.

A second approach, which was

explored in our lab by then graduate student Irene Chen, involved competition

between protocells. Model protocells filled with RNA or similar materials

became swollen, an osmotic effect resulting from the attempt of water to enter

the cell and equalize its concentration inside and outside. The membrane of

such swollen vesicles thus came under tension, and this tension drove growth,

because adding new molecules relaxes the tension on the membrane, lowering the

en- ergy of the system. In fact, swollen vesicles grew by stealing fatty acids

from relaxed neighboring vesicles, which shrank.

In the past year Ting Zhu, a

graduate student in our lab, has observed the growth of model protocells after

feeding them fresh fatty acids. To our amazement, the initially spherical vesi-

cles did not grow simply by getting larger. In- stead they first extended a

thin filament. Over about half an hour, this protruding filament grew longer

and thicker, gradually transforming the entire initial vesicle into along, thin

tube. This structure was quite delicate, and gentle shaking (such as might

occur as wind generates waves on a pond} caused it to break into a num- ber of

smaller, spherical daughter protocells, which then grew larger and repeated the

cycle [see micrograph on page 59].

Given the right building blocks,

then, the formation of protocells does not seem that difficult: membranes

self-assemble, genetic polymers self-assemble, and the two components can be

brought together in a variety of ways, for example, if the membranes form

around preexisting polymers. These sacs of water and RNA will also grow, absorb

new molecules, compete for nutrients, and divide. But to become alive, they

would also need to reproduce and evolve. In particular, they need to separate

their RNA double strands so each single strand can act as a tem- plate for a

new double strand that can be handed down to a daughter cell.

This process would not have started

on its own, but it could have with a little help. Imagine, for example, a

volcanic region on the otherwise cold surface of the early earth (at the time,

the sun shone at only 70 percent of its current power). There could be pools of

cold water, perhaps partly covered by ice but kept liquid by hot rocks. The

temperature differences would cause convection currents, so that every now and

then protocells in the water would be exposed to a burst of heat as they passed

near the hot rocks, but they would almost instantly cool down again as the

heated water mixed with the bulk of the cold water. The sudden heating would

cause a double he- lixto separate into single strands. Once back in the cool

region, new double strands-copies of the original one-could form as the single

strands acted as templates [see box on page 59].

As soon as the environment nudged

protocells to start reproducing, evolution kicked in. In particular, at some point some of the RNA sequences mutated,

becoming ribozymes that sped up the copying of RNA-thus adding a competitive

ad- vantage. Eventually ribozymes began to copy RNA without external help, It

is relatively easy to imagine how RNA- based protocells may have then evolved

[see box above]. Metabolism could have arisen gradually, as new ribozymes

enabled cells to synthesize nutrients internally from simpler and more abundant

starting materials. Next, the organisms might have added protein making to

their bag of chemical tricks. With their astonishing versatility, proteins

would have then taken over RNA's role in assisting genetic copying and

metabolism. Later, the organisms would have "learned" to make DNA,

gaining the advantage of possessing a more ro" bust carrier of genetic

information. At that point, the RNA world became the DNA world, and life as we

know it began.