HH-01-EarlyCivilzations4000-500BC

Early

Civilizations of the Near East 4000BC to 500 BC

†

†

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

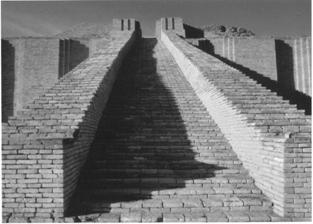

stepped ziggurat of Ur to honor Nanna the god of the moon

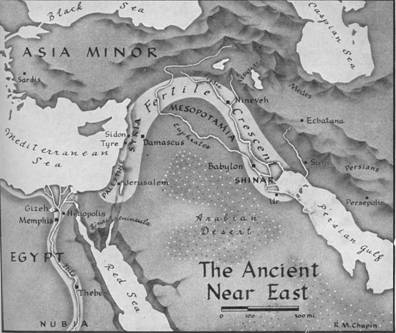

The Birthplace of Civilization

Early civilizations

emerged in the Tigris-Euphrates valley of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and the

Nile valley of Egypt between 4000 and 3000 BC in river valleys.† They also emerged in the Indus valley of

western India, China and Central America.†

The rivers of Egypt and Mesopotamia overflowed their banks each year

leaving a deposit of rich soil and provided water enabling people to produce

sizable harvests. Both river valleys were quite narrow, and were surrounded by

huge expanses of desert.

By 3200 BC some

form of government had developed in both river valleys. The emergence of small

city‑states was one of the first examples of urban life in the Near East,

although settled communities had existed as early as 6000 BC in places like

Jerico.

Institutions as

schools and law codes also developed. The invention of writing, the development

of physics, astronomy, and mathematics, plus the art of smelting, were

additional factors in the emergence of civilized society.

Generally speaking,

Egypt was less susceptible to the invasions of the semicivilized groups that

repeatedly entered the Tigris‑Euphrates valley. Distance, rather than

formidable natural frontiers, seems to have been the chief factor.† For this reason Egypt developed in relative

isolation until the Hyksos invasion.

The Civilization of Mesopotamia

The Sumerians† By 4000 BC the

Sumerians had settled in the Tigris‑Euphrates valley, their place of

origin unknown.† By 3000 B.C. many

important city‑states appeared in Sumer. Among them were Ur, Eridu,

Lagash, and Nippur. These cities were fiercely jealous of their independence,

and one city seldom predominated for very long.† Each city-state was administered by an official called a patesi.

He represented the highest political, religious, and military authority. A

patesi who was able to conquer a large number of city‑states was

dignified with the title of lugal, or king.††

The First Dynasty of Ur (c. 2500‑2300 BC) produced a line that

dominated most of Sumer and part of Akkad for two centuries.† Around 2275 BC Lugal Zaggisi of Uruk made

himself master of Mesopotamia.† Soon

thereafter Sargon I of Agade overthrew Lugal Zaggisi and inaugurated a period

of Semitic hegemony.

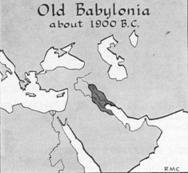

The Akkadians† Akkadian power was

centered about the city of Babylon.†

Akkadian armies controlled the entire Tigris‑Euphrates valley as

far north as the Taurus Mountains. Some authorities even believe that Sargon I

subjugated Syria.† Sargon I, the

"king of battle," divided his empire into districts ruled by the

"sons of the palace." Revolts were common, nevertheless, and these so

weakened the Akkadians that they were overwhelmed by the Guti around 2150

BC.† During their brief period of

dominance, the Akkadians dropped their nomadic ways and adopted much of

Sumerian culture.† Akkadian cultural

acquisitions included cuneiform writing, the Sumerian system of weights and

measures, and the Sumerian calendar.†

The Akkadians surpassed their Sumerian teachers in the art of seal

cutting and stone sculpture.

The Guti† This uncivilized

people swept into Mesopotamia around 2150 BC from their home in the Zagros

Mountains of Persia. They routed the weak Akkadian successors of Naram‑Sin.† These Semitic conquerors had several capable

leaders during their short period of dominance (c. 2150‑2070 BC). Among

the better kings were Irridu‑Pizir, Lasirab, and Tirigan.

Sumerian

revival† Around

2070 BC the Guti were driven out by Utu Khegal of Erech. The Sumerians were

able to reestablish their authority under the Third Dynasty of Ur.† Commerce thrived, and cultural achievement

reached its zenith.† Dungi, the

"King of the Four Quarters," was the most important monarch of this

dynasty. He is known for his excellent law code.† Dynastic conflicts were responsible for the sharp decline of

Sumerian power after 2000 BC. †Both the

Elamites and Amorites (Babylonians) poured into Mesopotamia to fill the power

vacuum left after the decline of the Third Dynasty of Ur.í

The Amorites

(Babylonians)† This

Semitic people moved into Mesopotamia from Syria around 2000 BC.† Only the Elamites offered resistance, since

the hostile Sumerian dynasties of Isin and Larsa were engaged in petty

quarrels.† The Amorites fended off the

Elamite challenge and ruled Mesopotamia until the Kassite incursion around 1670

BC.† The greatest Amorite ruler was

Hammurabi (1728‑1686 BC).† He

created a permanent administration for his domains, set up law courts, a system

of taxation, and rules for military service.††

His numerous letters mark him as a model administrator.† Hammurabi's Code of Laws was the greatest

legacy he left. Its 282 paragraphs were based on Sumerian and Semitic

precedents. It dealt with property rights, personal injuries, family affairs,

and a host of other matters.

†

† †

†

†

† †

†

Mesopotamian

culture

†

† †

† †

†

†††† Cueiform Tablet††††††††††† ††††††Sargon††† Sumerian woman appeal to heaven† Arch†††† Hammurabi†

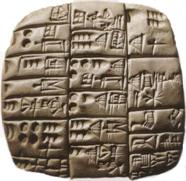

The Sumerians must

be given credit for the basic cultural contributions.† Prior to 3000 B.C. the Sumerians had developed a wedge‑shaped

writing called cuneiform. The signs

were pressed into small clay tablets with a reed and then dried in the sun or

baked. Other Near Eastern peoples adapted the Sumerian signs.† The Sumerians used a sexagesimal system of

counting. Ten was the basic number, sixty the next, and then six hundred.†† A lunar year of 12 months was devised. It

contained 354 days.†† The Sumerians

developed a system of weights and measures. It was based on the mina which weighed a we more than a

pound.†† Civil law was first compiled by

the Sumerians, and provided a basis for the subsequent Hammurabi Code. The lex talionis principle of proportionate

retaliation was a feature of Sumerian law.††

The Sumerians left an extensive literature in the form of epics, hymns,

and proverbs. Many were copied by the later Babylonians.†† The Gilgamesh Epic, a tale reminiscent of

Noah, is one of the great Sumerian literary contributions.†† The Babylonian Creation Epic is somewhat

similar to the Hebrew account found in Genesis.†† The Sumerians and their successors were polytheistic, their

faith offered no hope of resurrection.†

The Sumerians did not mummify the dead or build elaborate tombs for

them.† Sumerian deities had all of the

strengths and weaknesses of mortals.†

The Sumerian religion did not demand definitive standards of morality

from its adherents.

†

†

A signature seal and its impression, showing a Sumerian ruler in

audience with his local god.† Sumerian

harp with gold bulls head

†

†

Marduk replaced

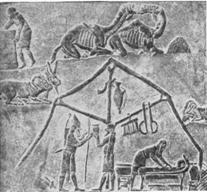

Tammuz as the leader of the gods during the Amorite (Babylonian) period.† The vault, arch, and dome were all

inventions of the Sumerians.† Their best

known structure was the ziggurat, a

pyramidal tower with a shrine at the top.†

In the absence of stone, sun‑dried brick was used.† Sculpture and metal work were two additional

areas in which Sumerian artisans excelled.

Egyptian

Civilization

The land of Egypt

was concentrated along a 550‑mile stretch of the Nile valley. The average

width of the cultivable land was but 12 miles. In all, Egypt had only 13,000

square miles of good soil to support a population of 7 million.† On both sides of the Nile valley was desert.

This made for a compact society in the river valley.† Egyptian civilization emerged into the light of history during

the fourth millennium BC. Its 3000‑year history during the ancient period

was divided into thirty dynasties by the historian Manetho (c. 280 BC).

The Predynastic

Period (4000‑3200 BC)† During these eight centuries the Egyptians

developed a system of writing, an irrigation network, a calendar, and a system

of government.† Egypt was divided into nomes or provinces. Each was governed by

a nomarch who collected taxes,

rendered justice, and commanded the local militia.† The various nomarchs quarrelled among themselves like so many

feudal princes.

The Protodynastic

Period (3200‑2750

BC)† Around 3100 BC the legendary Menes

supposedly united Upper and Lower Egypt.†

Some internal conflict continued until the founding of the Third Dynasty

by Khasekemui in 2980 BC.

The Old Kingdom.

(2750‑2270 BC)†

Dynasties III‑VI ruled Egypt from the city of Memphis.† This was the era of pyramid building.†† These structures reached the peak of

magnificence during the Fourth Dynasty, particularly the Great Pyramid of

Cheops at Gizeh.† The first pyramid was

probably built during the reign of Zoser by his adviser Imhotep.† During this period the Pharaohs had almost

absolute authority.† Egypt reached its

greatest size during the reign of Pepi II, but the weak rulers of the Sixth

Dynasty lost control after his death.†

Ra, the sun deity, headed the Egyptian pantheon. †The First Intermediate Period (2270‑2160

BC): this was a feudal age. The nobility was able to assert itself during the

chaotic century that ensued. Dynasties VII‑X ruled as the cities of

Memphis, Heracleopolis, and Thebes fought for the leadership of the Nile

valley.

†

†

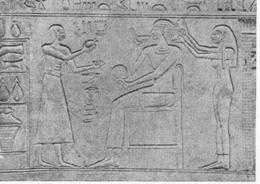

Duck hunting for this Egyptian is a matter of decoying the ducks

from his papyrus boat and hitting them with his boomerang

An

Egyptian princess is having her hair set in tight curls, holds a mirror,

beverage in the other, servant fixes her another .

†

†

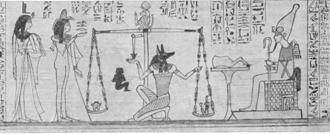

Osiris sits in judgment as his dog-headed creature weighs the

heart of a: princess against a feather. Isis stands behind the princess.

Theban

wall painting of† ceremonial farewell to

the dead, on tomb of two Egyptian sculptors.

†

† †

†

The Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Karnak, showing Clerestrory

Windows (reconstruction)

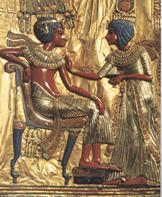

Portrait of Pharaoh Ramses II† Stone block statue of the Pharaoh Khafre

†

†

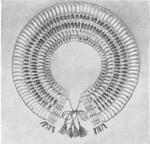

Egyptian

Dancing Girls (wall painting)††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† An Egyptian collar of beads

Middle Kingdom

(2160‑1788 BC)†

Order was restored when the Eleventh Dynasty of Thebes was able to win

control of Egypt.† The patron deity of

Thebes, Amun, became identified with Ra as head of the Egyptian pantheon.† The Middle Kingdom reached its apex under

Dynasty XII, particularly Pharaohs like Senwosret II and III.†† This was the classical period of Egyptian

literary achievement. Painting and sculpture flourished.† Trade with Syria and Punt was extensive. In

addition, irrigation was pushed and a dam built in the Fayuni area to store

water in the event that the Nile was low.

Second Intermediate

Period (1788‑1680

BC)† This was another feudal period

during which chaotic conditions existed.†

The weak Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasties were the nominal rulers.†

The Hyksos Era

(1680‑1580 BC)†

The Hyksos were probably Syrian and Palestinian Semites driven south

into Egypt by Indo‑European peoples from north of the Black and Caspian

Seas.† They were called "shepherd

kings" or "rulers of foreign lands."† Their invasion ended 2000 years of Egyptian isolation. After this

attack, Egypt played an important role in Near Eastern affairs.† Avaris, in Lower Egypt, became the Hyksos

capital. Upper Egypt sent tribute to the Hyksos, but that area remained

unoccupied.†† The Hyksos readily adopted

Egyptian culture and the old state administration.†† The horse and chariot were brought to Egypt by the Hyksos.†† The Hyksos were expelled by Ahmose I of

Thebes, founder of Dynasty XVII.

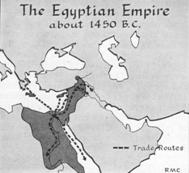

The New Empire‑(1580‑1090

BC)† Ahmose I pursued the Hyksos into

Asia and laid the foundation for the Egyptian expansion that followed.†† Under Thutmose 1 (1525‑1508 BC)

Palestine and Syria were temporarily overrun.†

The great Thutmose 111 (1501‑1447 BC) crushed the Kadesh

Confederacy and made Egyptian authority paramount in Syria and Palestine.† Egypt reached the pinnacle of her power

during the "golden age" of Amenhotep III (1411‑1375 BC).† During the reign of Amenhotep IV (Ikhnaton)

decline became evident.† The Pharaoh did

nothing to meet the new Hittite challenge.†

Amenhotep IV created an internal rift by experimenting with the

monotheistic Aton faith.† Ramses 11

(1292‑1225 BC) managed to hold his decaying state together despite the

ambush at Kadesh by the Hittites (1288 BC)††

The New Empire came to an end in 1090 BC when the priest Hrihor founded

Dynasty XXI,

The Period of

Decline (1090‑525

BC)† This was an era of weak kings and

powerful priests.† Libyan and Ethiopian

invaders often ruled the land.† A short

Assyrian occupation occurred in the seventh century BC.† Saite Revival (663‑525 BC)† Began under Psamtik I who expelled the

Assyrians.† The culture of the period

was a slavish imitation of past accomplishments. Cambyses and his Persian

armies conquered Egypt in 525 BC.

Egyptian

cultural and economic accomplishments

As early as 4241 BC

the Egyptians may have worked out a calendar.††

The people of the Nile valley developed several systems of writing prior

to the advent of the Fourth Dynasty.††

These included hieroglyphics, a

sacred form of writing that included 600 signs. The use of the Rosetta Stone

plus other materials enabled Champollion to decipher this language.† A cursive script called hieratic was developed at a later time. It was used for public and

commercial affairs.† The commoners of

Egypt came to use a still more abbreviated script called demotic† †Egyptian literature reached a zenith during

the Middle Kingdom with such works as The

Shipwrecked Sailor and The Tale of

the Eloquent Peasant.† Sculpture

became conventionalized by the Middle Kingdom. Statues had to have arms at the

sides and the left foot thrust forward.†

The Medical Papyri indicate

that the Egyptians were making some progress in the art of healing. These New

Empire records contain many worthless remedies, but they were the first documents

in which medical data was assembled.†

Significant advances were also made in geometry, astronomy, and

chemistry.

†

† †

† †

†

Old Kingdom

religious beliefs centered about the immortality of the Pharaoh. This solar

faith did not grant a life in the next world to the masses. During the Middle

Kingdom the people were able to reach this exalted state because of the god

Osiris.† Ra and Osiris vied for

supremacy.†† The Egyptian religion

placed no emphasis on an ethical life.†

Prayers and magical formulae from the Book of the Dead were sold by

priests. These could appease Osiris, and help insure immortality.

Egypt developed an

extensive trade with Syria, Crete, and Punt during the Middle Kingdom.† Wheat, gold wares, and linen were exported.

Ivory, cedar wood, tapestries, and ebony were imported.† Copper mining, tanning, stone quarrying, and

bronze making were important local industries.†

Agriculture was the basic occupation of most Egyptians.

The

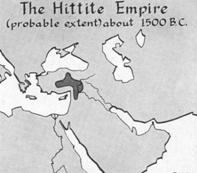

Empire of the Hittites

The Hittites

emanated from central and southeastern Asia Minor, present‑day

Turkey.† Agriculture and shepherding

were their main occupations. They were the first to smelt iron in

quantity.† The chief deity of the

Hittites was Teshub, but the sun goddess Arinna also had a place of

prominence.† The Hittite king derived

his authority from a council of nobles called the pankus.† By 1500 BC. the

Hittites had developed a legal code noted for its humane features.† The Hittites spoke an Indo‑European

language. It was deciphered by the Czech scholar Hrozny. †After 1900 BC the Hittites began to press

south into Syria from their citadel at Hattusas. Under Mursilis 1 (1620‑1590

BC) the loose confederation of city‑states was changed into a powerful

empire. Egyptian power in Syria was challenged by the Hittites until the

Mitanni brought about a temporary eclipse of their power (1500‑1375

BC).† Shubbiluliuma (1375‑1335

BC) again brought a revived Hittite empire into conflict with Egypt.† The continual invasions of the Sea Peoples

resulted in the destruction of the Hittite realm around 1190 BC.

Other Near Eastern States (2000‑1200 BC)

The Elamites† This people was

subject to Sumerian and Akkadian rule during most of the third millennium

BC.† For a brief period around 2000 BC

the Elamites pressed into Mesopotamia from the cast, but were later beaten by

Hammurabi and the Amorites.† Most of our

evidence for the study of Elamite history has come from the capital city of

Shusan (Susa

The Kassites† This Indo‑European

group moved into the Tigris‑Euphrates valley from the Iranian highlands

to the east around 1677 BC.† The Kassite

attack was led by Gandash. Amorite resistance was quickly overcome.† It is believed that the Kassites brought the

horse to Mesopotamia.†† The Kassites

waged a war against the Hittites under Agum II. By 1169 BC Assyrian, Median,

Babylonian, and Elamite pressure put an end to the Kassite kingdom.

The Hurrians† This Armenoid

people probably came ‑from the Lake Van region of present day Turkey.

Around 1800 B.C. they migrated southward and overran parts of Syria and

Palestine.† They probably brought the

horse‑drawn chariot into western Asia.†

Their language may be related to that of the Elamites.† The chief deities of the Hurrians were

Teshub, the storm god, and Hepa, the sun goddess.† It is likely that the Hurrians were absorbed by other peoples of

Syria and Palestine.

The Mitanni† The Mitanni

occupied an area that included much of northern Syria and Mesopotamia (1500

BC).† Under Sauslishattar, the Mitanni

held off the Egyptian forces of Thutmose III and kept the Assyrians in

subjugation.† By 1300 BC the rising

state of Assyria crushed the Mitanni. Soon thereafter the kingdom disappeared.

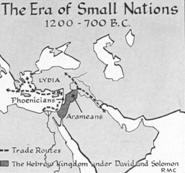

The

Era of Small States (1200‑800 BC)

With the decline of

Egyptian and Hittite power after 1200 BC, the Near East entered an era notable

for the absence of great powers.

†

† †

†

Hittite†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Lydian††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† Phrygian

The Phrygians† It is believed that

the Phrygians came to Asia Minor from eastern Greece around 1200 BC. They

settled in central Anatolia (Turkey) west of the Halys River.† Phrygian power was great from 900 to about

547 BC, although it waned perceptibly after their defeat by the Lydians in 610

BC.† Because of their location and Greek

background, the Phrygians were able to transmit many Asiatic ideas and

practices to the peoples of the Mediterranean.†

Cybele, the Great Mother, was the chief deity of the Phrygians. She

headed the Phrygian fertility cult that was known for its wild ceremonies and

dances.

The Ludians† This people

occupied western Asia Minor, holding the territory between Phrygia to the east

and the Ionian coastal towns to the west.†

Lydia was an important power from the eighth to the sixth century BC.† Gyges founded the famous Mernmadae Dynasty

in 670 BC, but the Persians under Cyrus overran Lydia in 547 BC by seizing King

Croesus in the capital city of, Sardis.†

The Lydians were excellent craftsmen and merchants. They are credited

with the invention of metal coins.† The

Lydians made contributions in music and dancing. They also excelled in weaving

and purple dyeing.

The Arameans†† This Semitic people

came out of the Syrian desert in the fourteenth century BC.† The Hittites and Assyrians prevented them

from entering the Tigris valley a century later.† An Aramean kingdom was organized around Damascus in the tenth

century BC. Other Arameans drifted into Mesopotamia in considerable

numbers.† The Arameans were noted for

their ability in international trade. Their language was

used everywhere in the Near East.

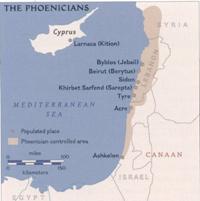

The

Phoenicians†† This

nation of sea‑traders lived in the

excellent coastal ports along what is now the shore of Lebanon.† The main Phoenician cities were Acre, Tyre,

Sidon, and Byblos.† After the decline of

Minoan and Mycenaean seapower in the twelfth century BC, the Phoenicians

succeeded in dominating the commercial life of the Mediterranean.† Phoenician colonies were established in

Carthage, Cyprus, and southern Spain.†

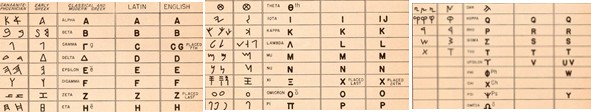

The greatest Phoenician contribution to civilization was their

alphabet. It had 22 consonants and no vowels, and may

have been based on Egyptian signs. It has become the basis for most ancient and

modern I alphabets.† For the better part

of the period 1500‑1300 BC Phoenicia was dominated by Egypt. From 1000‑774

BC the city of Tyre took the lead, but this was followed by a century and a

half of Assyrian domination.

†

† †

†

††††† Phoenician coast†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Phoenician carved ivory††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† Early metal artistry

The Hebrews† †This

Semitic people migrated from Egypt to Palestine around 1200 BC. As told in

Exodus, the Hebrew entrance into Palestine involved the subjugation of the

Canaanites. Moses led the Hebrews to Palestine and must be given credit for

welding them together as a nation.

Period of the

judges (c. 1200‑1030 BC)† This was

the era from the Exodus to the reign of Saul.††

The twelve Hebrew tribes formed a loose confederation. In times of war

certain leaders such as Samson, Gideon, or Samuel took charge. Collectively, they

are known as judges.† The judges

acquired a temporary judicial and military authority.† The rise of Saul as king of the Hebrews ended this era.

Under Saul (1030‑1005

BC) and David (1005‑965 BC) the Philistines, Edomites, and Moabites were

brought under control.† A sense of

national consciousness developed.† The

Hebrew kingdom reached its greatest size under David.

Under Solomon (965‑925

BC) the Hebrews made alliances with Egypt and Tyre.† A great building program was inaugurated at Jerusalem. Heavy taxation

and forced labor made the regime unpopular.†

After Solomon's death the Hebrew kingdom split into a southern state of

Judah and a northern state of Israel.

The kingdom of

Israel continued to exist for two centuries until the Assyrians under Sargon II

crushed it in 722 BC.

Judah managed to

maintain its independence until 586 B.C. when the Chaldeans under

Nebuchadnezzar seized Jerusalem.† Many

Hebrews were taken to Mesopotamia in the so‑called Babylonian Captivity

(586‑538 BC).† The Persian ruler

Cyrus permitted the Hebrews to return to Palestine in 538 BC.† The Hebrews remained under Achaemenid rule

until Alexander the Great conquered the area in 332 BC.

†

†

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Kingdom of Israel††

Hebrew

religion† It

was here that the Hebrews made their greatest contribution.† The Hebrew faith emphasized the belief in

one supreme deity, monotheism.† Yahweh

was the one god of the Hebrews.† The

Hebrew religion demanded an adherence to ethical standards. Such prophets as

Amos and Ezra often called the leaders and populace to task for lax moral

behavior.† The Torah or Pentateuch (Five

Books of Moses) contained the teachings of God as revealed through the prophets

or discovered by the sages.† Ezra must

be given credit for giving the Torah its position of importance. Its 613

commandments provided the Hebrews with a rigid code of personal and ritualistic

behavior. It is believed that much of the Torah may date from the Hebrew trek

through Sinai.† The Hebrew faith had a

great influence on several religions that emerged at a later time.

Christianity, for example, borrowed much of its theology as well as the Ten

Commandments.

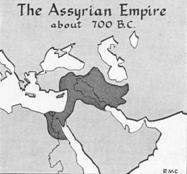

Assyrian Dominance in the Near East

The Assyrians lived

in the northeast corner of the Fertil Crescent. Their key Centers were Assur, Arbela and Nineveh.† Prior to 1300 BC the Assyrians were

dominated by the Sumerians, Akkadians, Elamites, and Amorites. Assyna expansion

began with the reign of Adadnirari (1310-1280 BC). Hittite, Egyptian, and Kassite

decline were important factors in the rise of Assyria.† After two centuries of temporary decline

(1100‑885 BC) the Assyrians began a period of revival by reorganizing

their army and government. Two hundred years of expansion followed with the

zenith of power being reached under Sargron II (722‑705 BC).† After the death of Assurbanipal in 626 BC

decline came quickly. The Babylonians and Medes razed Nineveh in 612 BC, and Assyrian military power

was permanently destroyed.

†

†

Assyrians

Scenes

†

†

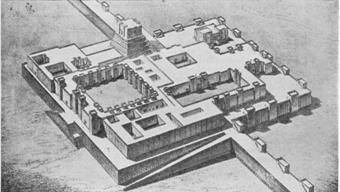

†††††††††††††††††††††† Lion

hunt from Assurbanipalís Palace†††††††††††††††

argon II Fortress Palace at Khorsaban (reconstruction)

Assyrian

civilization†† The

Assyrian army was the key institution. Its Prussian like efficiency made it the

terror of the Near East. The army committed fearful atrocities during its

conquests.† Most Assyrians were engaged

in agriculture. Many peasants were serfs.†

Commerce and industry were ignored by the dominant nobility.† The chief deity of the Assyrians was Assur,

a god that fought beside their soldiers in battle. The Assyrians had no belief

in a hereafter.† Although the Assyrians

did not generally excel in the arts, they did some fine work in stone sculpture

and palace building. Assurbanipal also compiled a library of 22,000 cuneiform

tablets at Nineveh.

†

†

Winged

Bull from Sargonís Palace

The Rise of Chaldea

††††††††††† The

Chaldeans were a Semitic people who settled in southern Mesopotamia. They

organized the Neo‑Babylonian Empire under Nabopolassar (625‑605

BC). In alliance with the Medes, the Chaldeans crushed the Assyrians and razed

Nineveh in 612 BC.† Under

Nebuchadnezzar (605‑562 BC) the Chaldeans reached their pinnacle.† Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine were

subjugated.† The famous Hanging Gardens

and Ishtar Gate adorned the city of Babylon. After Nebuchadnezzar's death decline

was rapid. The Persians under Cyrus seized Babylon in 539 BC.

Chaldean

civilization†† The

Chaldeans identified their deities with the planets. Marduk, for example, was

linked to Jupiter.† Deities could no

longer be influenced by man.† The gods

were all‑powerful, but their intentions were unknown.†† Since the desires of the deities could not

be learned, the Chaldeans fatalistically submitted themselves to the will of

the gods.† Like their Sumerian

predecessors, the Chaldeans had no interest in the hereafter.† The Chaldeans prayed for material betterment

on earth. They were not particularly interested in ethical values.

Chaldean

science†† The

Chaldeans could boast of many important achievements, particularly in

astronomy. Chaldean astronomers worked out a 7‑day week and a 24‑hour

day.† The study of astronomy was

motivated by the Chaldean desire to better understand the wishes of the

gods.† The Chaldeans showed no

particular originality in literature or the other arts.

Imperial

Persia and Her Civilization

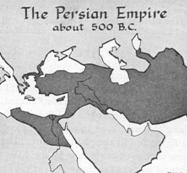

The Persians were

an Aryan people who came to Iran from the east around 650 BC.†† For a considerable period the Persians were

subjected to Mede overlordship, but the successful revolt of Cyrus around 550

BC ended that state of affairs.† Cyrus

founded the Achaemenid Dynasty (559‑331 BC) which lasted until its

destruction by Alexander the Great.† By

539 BC Cyrus had conquered Chaldea, Lydia, Syria, and Palestine. His successor,

Cambyses (529‑522 BC), added Egypt to the Persian domains.

Under Darius (521‑485

BC) the empire was reorganized on a more efficient basis.† The empire was divided into administrative

districts called satrapies. A satrap, or governor, ruled ear district.† The satrap was kept under close observation

by nth officials of the king. This procedure was effective on] during the reign

of a strong ruler like Darius. Darius' plans to crush Greece were made known

toward the end of his reign. He was angered by the aid the Geeks gave to the

cities of Ionia.† His first attempt

failed in 492 B.C. because a storm destroyed the expedition.† Darius made a second try in 490 BC, but the

Athenians defeated his forces at Marathon.

Xerxes (485‑465

BC) continued the campaign against Hellas.†

Persia suffered a crushing naval defeat at Salamis in 480 BC. Her land forces

were beaten decisively at Plataea in 479 BC.†

The Greek war dragged on for three additional decades until it was

officially ended by the Peace of Cimon in 449 BC.†† After Xerxes, Persian power and prestige sank to a new low.† Intrigue and internal strife (Satrap's War)

were responsible.† Persia became a ripe

target for the ambitious Alexander the Great.

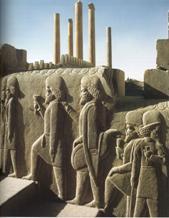

These old men are subjects from Syria on the .other side of the

Fertile Crescent, bringing gifts to the emperor at Persepolis - gold vessels,

bracelets, horses, even a chariot. This relief decorated a wall of Xerxes'

palace at Perspolis.

Persian

civilization

The Zoroastrian

religion† The

Persians permitted the worship of deities other than the Zoroastrian.†† Zoroastrian dualism made Ahura‑Mazda

the personification of good, while Ahriman represented all that was evil.† These two deities were engaged in a battle

for supremacy, but Ahura‑Mazda would win in the end.† The Zoroastrian faith predicted the coming

of a judgment day.† The Zoroastrian

faithful believed that a messiah, Saoshyant, would come prior to the end of

this world.† Zoroastrianism demanded an

ethical and temperate life. It was a revealed faith whose secrets were received

by Zoroaster from Ahura‑Mazda. Many tenets and ideas were recorded in the

sacred Avesta.†

The Persian Empire

was divided into 20 satrapies for administrative purposes.† Excellent roads serviced this vast empire.

Particularly important was the royal road between Susa and Sardis.† Because of the excellent network of roads, a

fine postal system existed.† Most

Persians were peasants. They were ruled by a powerful nobility.† Important cities were few in number. Susa

was the capital, but Persepolis, Pasargadae, and Ecbatana were also

important.† Palace building was one of

the few architectural achievements of the Persians. The arch was not used.† The Persians did little original work in

art. They borrowed heavily from the Babylonians, Hittites, and Egyptians.

The

ruined palace of Xerxes at Persepolis, showing columns and typical palace

platform.

†

†