H-Evolution-007Animals

Evolution

of Animals

Origin

of Animal Diversity

Animal life began in Precambrian seas with

the evolution of multiceluar creatures that ate other organisms.

We are among their descendants.

What

is an Animal?

Animals are

eukaryotic, multicellular, heterotrophic organisms that obtain nutrients by

ingestion -- ingestion means eating food. This mode of nutrition contrasts

animals with fungi, which obtain nutrients by absorption after digesting the

food outside the body. Animals digest their food within their bodies after

ingesting other organisms, dead or alive, whole or by the piece (Figure 17.2).

Most animals

reproduce sexually. The zygote (fertilized egg) develops into an early

embryonic stage called a blastula, which is usually hollow ball of cells

(Figure 17.3). The next embryonic stage in most animals is a gastrula, which

has layers of cells that will eventually form the adult body parts. The

gastrula also has a primitive gut, which will develop into the animal's

digestive compartment. Continued development, growth, and maturation transform

some animals directly from the embryo into an adult. However many animals

include larval stages. A larva is a sexually immature form of an animal. It is

anatomically distinct from the adult form, usually eats different foods, and

may even have a different habitat. Think how different a frog is from its

larval form, which we calla tadpole. A change of body form, called

metamorphosis, eventually remodels the larva into the adult form.

Figure 17.2 Nutrition by ingestion, the animal way of life. Most

animals ingest relatively large pieces of food, though rarely as large as the

prey in this case. In this amazing scene, a rock python is beginning to ingest

a gazelle. The snake will spend two weeks or more in a quiet place digesting

its meal.

Figure 17.3 Life cycle of a sea star as an example of animal

development. (1) Male and female adult animals produce haploid gametes (eggs

and sperm) by meiosis. (2) An egg and a sperm fuse to produce a diploid zygote.

(3) Early mitotic divisions lead to an embryonic stage called a blastula,

common to all animals. Typically, the blastula consists of a ball of cells

surrounding a hollow cavity. (4) Later, in the sea star and many other animals,

one side of the blastula cups inward, forming an embryonic stage called a

gastrula. (5) The gastrula develops into a saclike embryo with a two-layered

wall and an opening at one end. Eventually, the outer layer (ectoderm) develops

into the animal's epidermis (skin) and nervous system. The inner layer

(endoderm) forms the digestive tract. Still later in development, in most

animals, a third layer (mesoderm) forms between the other two and develops into

most of the other internal organs (not shown in the figure). (6) Following the

gastrula, many animals continue to develop and then mature directly into

adults. But others, including the sea star, develop into one or more larval

stages first. (7) The larva undergoes a major change of body form, called

metamorphosis, in becoming an adult-a mature animal capable of reproducing

sexually.

Most animals have

muscle cells, as well as nerve cells that control the muscles. The evolution of

this equipment for coordinated movement enhanced feeding, even enabling some

animals to search for or chase their food. The most complex animals, of course,

can use their muscular and nervous systems for many functions other than

eating. Some species even use massive networks of nerve cells called brains to

think.

Figure 17.4 One hypothesis for a sequence of stages in the origin

of animals from a colonial protist. (1) The earliest colonies may have

consisted of only a few cells, all of which were flagellated and basically

identical. (2) Some of the later colonies may have been hollow spheres-floating

aggregates of heterotrophic cells-that ingested organic nutrients from the

water. (3) Eventually, cells in the colony may have specialized, with some

cells adapted for reproduction and others for somatic (non-reproductive)

functions, such as locomotion and feeding. (4) A simple multicellular organism

with cell layers may have evolved from a hollow colony, with cells on one side

of the colony cupping inward, the way they do in the gastrula of an animal

embryo (see Figure 17.3). (5) A layered body plan would have enabled further

division of labor among the cells. The outer flagellated cells would have

provided locomotion and some protection, while the inner cells could have

specialized in reproduction or feeding. With its specialized cells and a simple

digestive compartment, the proto-animal shown here could have fed on organic

matter on the sea floor.

Figure 17.5 A Cambrian seascape. drawing based on fossils

collected at a site called Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada.

Early Animals and the Cambrian Explosion

Animals probably evolved from a colonial,

flagellated protist that lived in Precambrian seas (Figure 17.4) .By the late

Precambrian, about 600-700 million years ago, a diversity of animals had

already evolved. Then came the Cambrian explosion. At the beginning of the

Cambrian period, 545 million years ago, animals underwent a relatively rapid

diversification. During a span of only about 10 million years, all the major

animal body plans we see today evolved. It is an evolutionary episode so

boldly marked in the fossil record that geologists use the dawn of the Cambrian

period as the beginning of the Paleozoic era. Many of the Cambrian animals seem

bizarre compared to the versions we see today, but most zoologists now agree

that the Cambrian fossils can be classified as ancient representatives of

contemporary animal phyla (Figure 17.5).

What ignited the Cambrian explosion?

Hypotheses abound. Most researchers now believe that the Cambrian explosion

simply extended animal diversification that was already well under way during

the late Precambrian. But what caused the radiation of animal forms to

accelerate so dramatically during the early Cambrian? One hypothesis emphasizes

increasingly complex predator-prey relationships that led to diverse

adaptations for feeding, motility, and protection. This would help explain why

most Cambrian animals had shells or hard outer skeletons, in contrast to

Precambrian animals, which were mostly soft-bodied. Another hypothesis focuses

on the evolution of genes that control the development of animal form, such as

the placement of body parts in embryos. At least some of these genes are common

to diverse animal phyla. However, variation in how, when, and where these genes

are expressed in an embryo can produce some of the major differences in body

form that distinguish the phyla. Perhaps this developmental plasticity was

partly responsible for the relatively rapid diversification of animals during

the early Cambrian. In the last half

billion years, animal evolution has mainly generated new variations of old

"designs" that originated in the Cambrian seas.

Animal

Phylogeny

Because animals

diversified so rapidly on the scale of geologic time, it is difficult, using

only the fossil record, to sort out the sequence of branching in animal

phylogeny. To reconstruct the evolutionary history of animal phyla, researchers

must depend mainly on clues from comparative anatomy and embryology. Molecular

methods are now providing additional tools for testing hypotheses about animal

phylogeny. Figure 17.6 represents one set of hypotheses about the evolutionary

relationships among nine major animal

phyla. The circled numbers on the tree highlight four key evolutionary branch

points, and these numbers are keyed to the following discussion.

(1) The first branch point distinguishes sponges from all other

animals based on structural complexity. Sponges, though multicellular, lack the

true tissues, such as epithelial (skin) tissue, that characterize more complex

animals.

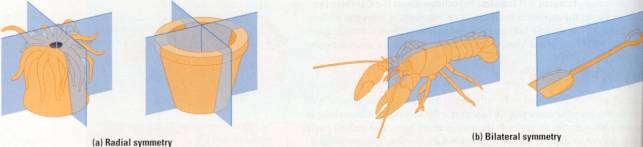

(2) The second major

evolutionary split is based partly on body symmetry: radial versus bilateral.

To understand this difference, imagine a pail and shovel. The pail has radial

symmetry. identical all around a central axis. The shovel has bilateral

symmetry, which means there's only one way to split it into two equal

halves-right down the midline. Figure 17.7 contrasts a radial animal with a

bilateral one.

The symmetry of

an animal generally fits its lifestyle. Many radial animals are sessile forms

(attached to a substratum) or plankton (drifting or weakly swimming aquatic

forms). Their symmetry equips them to meet the environment equally well from

all sides. Most animals that move actively from place to place are bilateral. A

bilateral animal has a definite "head end" that encounters food,

danger, and other stimuli first when the animal is traveling. In most bilateral

animals, a nerve center in the form of a brain is at the head end, near a

concentration of sense organs such as eyes. Thus, bilateral symmetry is an

adaptation for movement, such as crawling, burrowing, or swimming.

Figure 17.7 Body symmetry. (a) The parts of a radial animal, such

as this sea anemone, radiate from the center. Any imaginary slice through the

central axis would divide the animal into mirror images. (b) A bilateral

animal, such as this lobster, has a left and right side. Only one imaginary cut

would divide the animal into mirror-image halves.

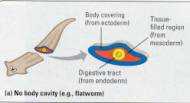

Figure 17.8 Body plans of bilateral

animals. The various organ systems of these animals develop from the three tissue

layers that form in the embryo. (a) Flatworms are examples of animals that lack

a body cavity. (b) Roundworms have a pseudocoelom, a body cavity only partially

lined by mesoderm, the middle tissue layer. (c) Earthworms and other annelids

are examples of animals with a true coelom. Acoelom is a body cavity completely

lined by mesoderm. Mesenteries, also derived from mesoderm, suspend the organs

in the fluid-filled coelom.

(3) The evolution of body

cavities led to more complex animals. A body cavity is a fluid-filled space

separating the digestive tract from the outer body wall. A body cavity has many

functions. Its fluid cushions the suspended organs, helping to prevent internal

injury. The cavity also enables the internal organs to grow and move independently

of the outer body wall. If it were not for your body cavity, exercise would be

very hard on your internal organs. And every beat of your heart or ripple of

your intestine would deform your body surface. It would be a scary sight. In

soft-bodied animals such as earth worms, the noncompressible fluid of the body

cavity is under pressure and functions as a hydrostatic skeleton against which

muscles can work. In fact, body cavities may have first evolved as adaptations

for burrowing.

Among

animals with a body cavity, there are differences in how the cavity develops.

In all cases, the cavity is at least partly lined by a middle layer of tissue,

called mesoderm, which develops between the inner ( endoderm) and outer (

ectoderm) layers of the gastrula embryo. If the body cavity is not completely

lined by tissue derived from mesoderm, it is termed a pseudocoelom (Figure

17.8) .A true coelom. the type of body cavity humans and many other animals

have, is completely lined by tissue derived from mesoderm.

(4)

Among animals with a true coelom. there are two main evolutionary

branches. They differ in several details of embryonic development. Including

the mechanism of coelom formation. One branch includes mollusks (such as clams,

snails, and squids). annelids (such as earthworms), and arthropods (such as

crustaceans, spiders. and insects). The two major phyla of the other branch are

echInoderms (such as sea stars and sea urchIns) and chordates (including humans

and other vertebrates).

Major Invertebrate Phyla

Living as we do on land, our sense of

animal diversity is biased in favor of vertebrates, which are animals with a

backbone. Vertebrates are well represented on land in the form of such animals

as reptiles, birds, and mammals. However, vertebrates make up only one

subphylum within the phylum Chordata, or less than 5% of all animal species. If

we were to sample the animals in an aquatic habitat, such as a pond, tide pool,

or coral reef, we would find ourselves in the realm of invertebrates. These are

the animals without backbones. It is traditional to divide the animal kingdom

into vertebrates and invertebrates, but this makes about as much zoological

sense as sorting animals into flatworms and nonflatworms. We give special

attention to the vertebrates only because we humans are among the backboned

ones. However, by exploring the other 95% of the animal kingdom-the

invertebrates-we'll discover an astonishing diversity of beautiful creatures

that too often escape our notice.

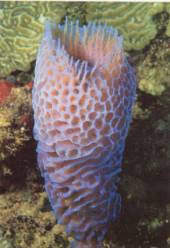

Sponges

Sponges (phylum

Porifera) are sessile animals that appear so sedate to the human eye that the

ancient Greeks believed them to be plants (Figure 17.9). The simplest of all

animals, sponges probably evolved very early from colonial protists. Sponges

range in height from about 1 cm to 2 m. Sponges have no nerves or muscles, but

the individual cells can sense and react to changes in the environment. The

cell layers of sponges are loose federations of cells, not really tissues,

because the cells are relatively unspecialized. Of the 9,000 or so species of

sponges, only about 100 live in fresh water; the rest are marine.

Figure 17.9 Sponge

Figure 17.10 Anatomy of a sponge. Feeding cells called choanocytes

have flagella that sweep water through the sponge's body. Choanocytes trap

bacteria and other food particles, and amoebocytes distribute the food to other

cells. To obtain enough food to grow by 100 g (about 3 ounces), a sponge must

filter 1,000 kg (about 275 gallons) of seawater.

The body of a

sponge resembles a sac perforated with holes (the name of the sponge phylum,

Porifera, means "pore bearer"). Water is drawn through the pores into

a central cavity, then flows out of the sponge through a larger opening (Figure

17.10). Most sponges feed by collecting bacteria from the water that streams

through their porous bodies. Flagellated cells called choanocytes trap bacteria

in mucus and then engulf the food by phagocytosis. Cells called arnoebocytes

pick up food from the choanocytes, digest it, and carry the nutrients to other

cells. Amoebocytes are the "do-all" cells of sponges. Moving about by

means of pseudopodia, they digest and distribute food, transport oxygen, and

dispose of wastes. Amoebocytes also manufacture the fibers that make up a

sponge's skeleton. In some sponges, these fibers are sharp and spur-like. Other

sponges have softer, more flexible skeletons; we use these pliant, honey-combed

skeletons as bathroom sponges.

Cnidarians

Cnidarians

(phylum Cnidaria) are characterized by radial symmetry and tentacles with

stinging cells. Jellies, sea anemones, hydras, and coral animals are all

cnidarians. Most of the 10,000 cnidarian species are marine.

The basic body

plan of a cnidarian is a sac with a central digestive compartment, the

gastrovascular cavity. A single opening to this cavity functions as both mouth

and anus. This basic body plan has two variations: the sessile polyp and the

floating medusa (Figure 17.11 ). Polyps adhere to the substratum and extend

their tentacles, waiting for prey. Examples of the polyp form are hydras, sea

anemones, and coral animals (Figure 17.12) .A medusa is a flattened, mouth-down

version of the polyp. It moves freely in the water by a combination of passive

drifting and contractions of its bell-shaped body. The animals we generally

call jellies are medusas (jellyfish is another common name, though these

animals are not really fishes, which are vertebrates). Some cnidarians exist

only as polyps, others only as medusas, and still others pass sequentially

through both a medusa stage and a polyp stage in their life cycle.

Figure 17.11 Polyp and medusa forms of cnidarians. Note that

cnidarians have two tissue layers, distinguished in the diagrams by blue and

yellow. The gastrovascular cavity is a digestive sac, meaning that it has only

one opening, which functions as both mouth and anus. {a) Sea anemones are

examples of the polyp form of the basic cnidarian body plan. {b) Jellies are

examples of the medusa form.

Figure 17.12 Coral animals. Each polyp in this colony is about 3

mm in diameter. Coral animals secrete hard external skeletons of calcium

carbonate (limestone). Each polyp builds on the skeletal remains of earlier

generations to construct the "rocks" we call coral. Though individual

coral animals are small, their collective construction accounts for such

biological wonders as Australia's Great Barrier Reef, which Apollo astronauts

were able to identify from the moon. Tropical coral reefs are home to an

enormous variety of invertebrates and fishes.

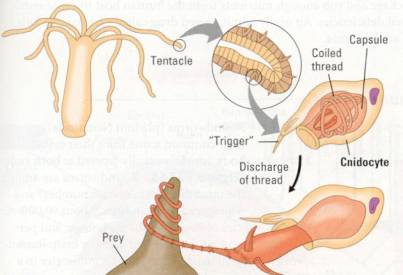

Figure 17.13 Cnidocyte action. Each cnidocyte contains a fine

thread coiled within a capsule. When a trigger is stimulated by touch, the

thread shoots out. Some cnidocyte threads entangle prey, while others puncture

the prey and inject a poison.

Cnidarians are

carnivores that use tentacles arranged in a ring around the mouth to capture

prey and push the food into the gastrovascular cavity, where digestion begins.

The undigested remains are eliminated through the mouth/anus. The tentacles are

armed with batteries of cnidocytes ("stinging cells"), unique

structures that function in defense and in the capture of prey (Figure 17.13).

The phylum Cnidaria is named for these stinging cells.

Flatworms

Flatworms (phylum

Platyhelminthes) are [ the simplest bilateral animals. True to their name,

these worms are leaf-like or ribbon-like, ranging from about 1 mm to about 20 m

in length. There are about 20,000 species of flatworms living in marine, fresh

water, and damp terrestrial habitats. Planarians are examples of free-living

(nonparasitic) flatworms (Figure 17.14) .The phylum also includes many

parasitic species, such as flukes and tapeworms.

Parasitic

flatworms called blood flukes are a huge health problem in the tropics. These

worms have suckers that attach to the inside of the blood vessels near the

human host's intestines. This causes a long-lasting disease with such symptoms

as severe abdominal pain, anemia, and dysentery. About 250 million people in 70

countries suffer from blood fluke disease. Flukes generally have complex life

cycles that require more than one host species. People are most commonly

exposed to blood flukes while working in irrigated fields contaminated with

human feces. Blood flukes living in a human host reproduce sexually, and

fertilized eggs pass out in the host's feces. If an egg lands in a pond or

stream, a motile larva hatches. This larva can enter a snail, the next host.

Asexual reproduction in the snail eventually produces other larvae that can

infect humans. A person becomes infected when these larvae penetrate the skin.

Tapeworms

parasitize many vertebrates, including humans. In contrast to planarians and

flukes, most tapeworms have a very long, ribbon like body with repeated parts

(Figure 17.15) .They also differ from other flatworms in not having any

digestive tract at all. Living in partially digested food in the intestines of

their hosts, tapeworms simply absorb nutrients across their body surface. Like

parasitic flukes, tapeworms have a complex life cycle, usually involving more

than one host. Humans can become

infected with tapeworms by eating rare beef containing the worm's larvae. The

larvae are microscopic, but the adults can reach lengths of 20 m in the human

intestine. Such large tapeworms can cause intestinal blockage and rob enough

nutrients from the human host to cause nutritional deficiencies. An orally

administered drug called niclosamide kills the adult worms.

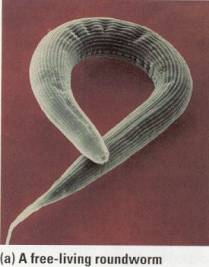

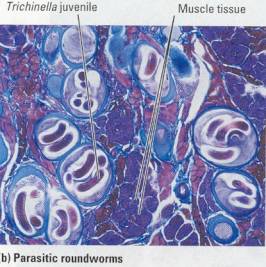

Roundworms

Roundworms

(phylum Nematoda) get their common name from their cylindrical body, which is

usually tapered at both ends (Figure 17.16a).Roundworms are among the most

diverse (in species number) and widespread of all animals. About 90,000 species

of roundworms are known, and perhaps ten times that number actually exist.

Round worms range in length from about a millimeter to a meter. They are found in

most aquatic habitats, in wet soil, and as parasites in the body fluids and

tissues of plants and animals. Free living roundworms in the soil are important

decomposers. Other species are major agricultural pests that attack the roots

of plants, Humans host at least 50 parasitic roundworm species, including

pinworms, hookworms, and the parasite that causes trichinosis (Figure 17.16b).

Figure 17.14 Anatomy of a planarian. This free-living flatworm has

a head with two light-detecting eye-spots and a flap at each side that detects

certain chemicals in the water. Dense clusters of nervous tissue form a simple

brain. The digestive tract is highly branched, providing an extensive surface

area for the absorption of nutrients. When the animal feeds, a muscular tube

projects through the mouth and sucks food in. The digestive tract, like that of

cnidarians, is a gastrovascular cavity (a single opening functions as both

mouth and anus). Planarians live on the undersurfaces of rocks in freshwater

ponds and streams.

Figure 17.15 Anatomy of a tapeworm. Humans acquire larvae of these

parasites by eating undercooked meat that is infected. The head of a tapeworm

is armed with suckers and menacing hooks that lock the worm to the intestinal

lining of the host. Behind the head is a long ribbon of units that are little

more than sacs of sex organs. At the back of the worm, mature units containing

thousands of eggs break off and leave the host's body with the feces.

Roundworms

exhibit two evolutionary innovations not found in flat-worms. First, roundworms

have a complete digestive tract, which is a digestive tube with two openings, a

mouth and an anus. This anatomy contrasts with the digestive sac, or

gastrovascular cavity, of cnidarians and flatworms, which uses a single opening

as both mouth and anus. All the remaining animals in our survey of animal phyla

have a complete digestive tract. A complete digestive tract can process food

and absorb nutrients as a meal moves in one direction from one specialized

digestive organ to the next. In humans, for example, the mouth, stomach, and

intestines are examples of digestive organs. A second evolutionary innovation

we see for the first time in roundworms is a body cavity, which in this case is

a pseudo coelom (see Figure 17.8).

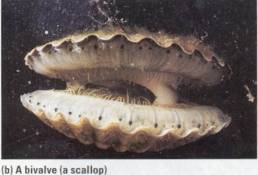

Mollusks

Snails and slugs,

oysters and clams, and octopuses and squids are all mollusks (phylum Mollusca).

Mollusks are soft-bodied animals, but most are protected by a hard shell. Slugs, squids, and octopuses have reduced shells,

most of which are internal, or they have lost their she»s completely during

their evolution. Many mollusks feed by using a strap-like rasping organ called

a radula to scrape up food. Garden snails use their radulas like tiny saws to

cut pieces out of leaves. Most of the 150,000 known species of mollusks are

marine, though some inhabit fresh water, and there are land-dwelling mollusks

in the form of snails and slugs.

Despite their

apparent differences, all mollusks have a similar body plan (Figure 17.17) .The

body has three main parts: a muscular foot, usually used for movement; a

visceral mass containing most of the internal organs; and a fold of tissue

called the mantle. The mantle drapes over the visceral mass and secretes the

shell (if one is present).

The three major

classes of mollusks are gastropods (including snails and slugs), bivalves

(including clams and oysters), and cephalopods (including squids and

octopuses). Most gastropods are protected by a single, spiraled shell into

which the animal can retreat when threatened (Figure 17.18a). Many gastropods

have a distinct head with eyes at the tips of tentacles (think of a garden

snail). Bivalves, including numerous species of clams, oysters, mussels, and

scallops, have shells divided into two halves hinged together (Figure 17.18b).

Most bivalves are sedentary, living in sand or mud in marine and freshwater

environments. They use their muscular foot for digging and anchoring.

Cephalopods generally differ from gastropods and sedentary bivalves in being

built for speed and agility. A few cephalopods have large, heavy shells, but in

most the shell is small and internal (as in squids) or missing altogether (as

in octopuses). Cephalopods are marine predators that use beaklike jaws and a

radula to crush or rip prey apart. The cephalopod mouth is at the base of the

foot, which is drawn out into several long tentacles for catching and holding

prey (Figure 17.18c).

Figure 17.16 Roundworms. (a) This species has the classic

roundworm shape: cylindrical with tapered ends. You can see the mouth at the

end that is more blunt. Not visible is the anus at the other end of a complete

digestive tract. This worm looks like it's wearing a corduroy coat, but the

ridges actually indicate muscles that run the length of the body. (b) The

disease called trichinosis is caused by these roundworms, encysted here in

human muscle tissue. Humans acquire the parasite by eating undercooked pork or

other meat that is infected. The worms then burrow into the human intestine and

eventually travel to other parts of the body, encysting in muscles and other

organs.

Annelids

Annelids (phylum

Annelida) are worms with body segmentation, which is the division of the body

along its length into a series of repeated segments that look like a set of

fused rings. Look closely at an earthworm, an annelid you have all encountered,

and you'll see why these creatures are also called segmented worms (Figure

17.19). In all, there are about 15,000

annelid species, ranging in length from less than 1 mm to the 3-m giant

Australian earthworm. Annelids live in the sea, most freshwater habitats, and

damp soil. The three main classes of annelids are the earthworms and their

relatives, the polychaetes, and the leeches.

Figure 17.17 The general body plan of a mollusk. Note the body

cavity (a true coelom, though a small one) and the complete digestive tract,

with both mouth and anus.

Earthworms eat

their way through the soil, extracting nutrients as the soil passes through the

digestive tube (Figure 17.208). Undigested material, mixed with mucus secreted

into the digestive tract, is eliminated as castings through the anus. Farmers

value earthworms because the animals till the earth, and the castings improve

the texture of the soil. Charles Darwin estimated that each acre of British

farmland had about 50,000 earthworms that produced 18 tons of castings per

year.

In contrast to

earthworms, most polychaetes are marine, mainly crawling or burrowing in the

seafloor. Segmental appendages with hard bristles help the worm wriggle about

in search of small invertebrates to eat. The appendages als-o increase the

animal's surface area for taking up oxygen and disposing of metabolic wastes,

including carbon dioxide (Figure 17.20b ).

The third group

of annelids, leeches, are notorious for the bloodsucking habits of some

species. However, most species are free-living carnivores that eat small

invertebrates such as snails and ins~cts. The majority of leeches live in fresh

water, but a few terrestrial species inhabit moist vegetation in the tropics.

Until the twentieth century, bloodsucking leeches were frequently used by

physicians for bloodletting, the removal of what was considered "bad

blood" from sick patients. Some leeches have razorlike jaws that cut

through the skin, and they secrete saliva containing a strong anesthetic and an

anticoagulant into the wound. The anesthetic makes the bite virtually painless,

and the anticoagulant keeps the blood from clotting. Leech anticoagulant is now

being produced commercially by genetic engineering and may find wide use in

human medicine. Tests show that it prevents blood clots that can cause heart

attacks. Leeches are also still occasionally used to remove blood from bruised

tissues and to help relieve swelling in fingers or toes that have been sewn

back on after accidents (Figure 17.20c). Blood tends to accumulate and cause

swelling in a reattached finger or toe until small veins have a chance to grow

back int9 it. Leeches are applied to remove the excess blood.

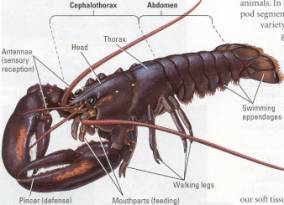

Arthropods

Arthropods

(phylum Arthropoda) are named for their Jointed appendages. {such as crabs and

lobsters), arachnids (such as spiders and scorpions), and insects are all

examples of arthropods. Zoologists estimate that the total arthropod population

of Earth numbers about a billion billion (1018) individuals.

Researchers have identified about a million arthropod species, mostly insects.

In fact, two out of every three species of life that have been described are

arthropods. And arthropods are

represented in nearlyall habitats of the biosphere. On the criteria of species

diversity, distribution, and sheer numbers, arthropods must be regarded as the

most successful of all animal phyla.

Figure 17.18 Mollusks. (a) Shell collectors are delighted by the

variety of gastropods. (b) This scallop, a bivalve, has many eyes peering out

between the two halves of the hinged shell. (c) An octopus is a cephalopod

without a shell. All cephalopods have large brains and sophisticated sense

organs, which contribute to the success of these animals as mobile predators. This

octopus lives on the seafloor, where it scurries about in search of crabs and

other food. Its brain is larger and more complex, proportionate to body size,

than that of any other invertebrate. Octopuses are very intelligent and have

shown remarkable learning abilities in laboratory experiments.

General

Characteristics of Arthropods

Arthopods are segmented animals. In contrast to the matching

segments of annelids, however, arthropod segments and their appendages have

become specialized for a great variety of functions. This evolutionary

flexibility contributed to the great diversification of arthropods.

Specialization of segments, or fused groups of segments, also provides for an

efficient division of labor among body regions. For example, the appendages of

different segments are variously modified (for walking, feeding, sensory

reception, copulation, and defense (Figure 17.21).

Figure 17.19 Segmented anatomy of an earthworm. Annelids are

segmented both externally and internally. Many of the internal structures are

repeated, segment by segment. The coelom (body cavity) is partitioned by walls

(only two segment walls are fully shown here). The nervous system (yellow)

includes a nerve cord with a cluster of nerve cells in each segment. Excretory

organs (green), which dispose of fluid wastes, are also repeated in each

segment. The digestive tract, however, is not segmented; it passes through the

segment walls from the mouth to the anus. Segmental blood vessels connect

continuous vessels that run along the top (dorsallocation) and bottom (ventral

location) of the worm. The segmental vessels include five pairs of accessory

hearts. The main heart is simply an enlarged region of the dorsal blood vessel

near the head end of the worm.

Figure 17.21 Arthropod characteristics of a lobster. The whole

body, including the appendages, is covered by an exoskeleton. The two distinct

regions of the body are the cephalothorax (consisting of the head and thorax)

and the abdomen. The head bears a pair of eyes, each situated on a movable

stalk. The body is segmented, but this characteristic is only obvious in the

abdomen. The animal has a tool kit of specialized appendages, including

pincers, walking legs, swimming appendages, and two pairs of sensory antennae.

Even the multiple mouthparts are modified legs, which is why they work form

side to side rather than up and down (as our jaws do).

The body of an

arthropod is completely covered by an exoskeleton (external skeleton). This

coat is constructed from layers of protein and a polysaccharide called chitin.

The exoskeleton can be a thick, hard armor over some parts, of the body yet

paper-thin and flexible in other locations, such as the joints. The exoskeleton

protects the animal and provides points of attachment for the muscles that move

the appendages. There are, of course, advantages to wearing hard parts on the

outside. Our own skeleton is interior to most of our soft tissues, an

arrangement that doesn't provide much protection from injury. But our skeleton

does offer the advantage of being able to grow along with the rest of our body.

In contrast, a growing arthropod must occasionally shed its old exoskeleton and

secrete a larger one. This process, called molting, leaves the animal

temporarily vulnerable to predators and other dangers.

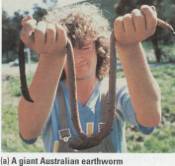

Figure 17.20 Annelids. (a) Giant Australian earthworms are bigger

than most snakes. Perhaps you've slipped on slimy worms, but imagine actually

tripping over one. (b) Polychaetes have segmental appendages that function in

movement and as gills. On the left is a sandworm. The beautiful polychaete on

the right is an example of a fan worm, which lives in a tube it constructs by

mixing mucus with bits of sand and broken shells. Fan worms use their feathery

head-dresses as gills and to extract food particles from the seawater. This

species is called a Christmas tree worm. (c) A nurse applied this medicinal

leech (Hirudo medicinalisl to a patient's sore thumb to drain blood from a

hematoma (abnormal accumulation of blood around an internal injury).

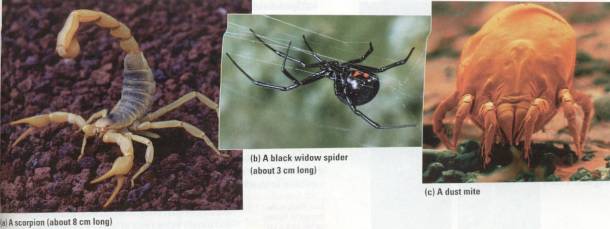

Arthropod

Diversity The four main groups of arthropods are the arachnids, the

crustaceans, the millipedes and centipedes, and the insects. Most arachnids

live on land. Scorpions, spiders, ticks, and mites are examples (Figure 17.22).

Arachnids usually have four pairs of walking legs and a specialized pair of

feeding appendages. In spiders, these feeding appendages are fanglike and

equipped with poison glands. As a spider uses these appendages to immobilize

and chew its prey, it spills digestive juices onto the torn tissues and sucks

up its liquid meal.

Crustaceans are

nearly all aquatic. Crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimps, and barnacles are all

crustaceans (Figure 17.23). They all exhibit the crustacean hallmark of

multiple pairs of specialized appendages (see Figure 17.21). One group of

crustaceans, the isopods, is represented on land by pill bugs, which you have

probably found on the undersides of moist leaves and other organic debris.

Figure 17.22 Arachnids. (a) Scorpions are nocturnal hunters. Their

ancestors were among the first terrestrial carnivores, preying on herbivorous

arthropods that fed on the early land plants. Scorpions have a pair of

appendages modified as large pincers that function in defense and food capture.

The tip of the tail bears a poisonous stinger. Scorpions eat mainly insects and

spiders. They will sting people only when prodded or stepped on. (If you camp

in the desert and leave your shoes on the ground when you go to bed, make sure

there are no scorpions in those shoes before putting them on in the morning.)

(b) Spiders are usually most active during the daytime, hunting insects or

trapping them in webs. Spiders spin their webs of liquid silk, which solidifies

as it comes out of specialized glands. Each spider engineers a style of web

that is characteristic of its species, getting the web right on the very first

try. Besides building their webs of silk, spiders use the fibers in many other

ways: as droplines for rapid escape; as cloth that covers eggs; and even as

"gift wrapping" for food that certain male spiders offer to seduce

females. (c) This magnified house dust mite is a ubiquitous scavenger in our

homes. Each square inch of carpet and every one of those dust balls under a bed

s are like cities to thousands of dust mites. Unlike some mites that carry

pathogenic bacteria, dust mites are harmless except to people who are allergic

to the mites' feces.

(a) A shrimp

(b) Barnacles Figure

17.24 A millipede

Figure 17.23 Crustaceans. (a) A grass shrimp. (b) Easily confused

with bivalve mollusks, barnacles are actually sessile crustaceans with

exoskeletons hardened into shells by calcium carbonate (lime). The jointed

appendages projecting from the shell capture small plankton.

Millipedes and

centipedes have similar segments over most of the body and superficially

resemble annelids, but their jointed legs give them away as arthropods.

Millipedes are landlubbers that eat decaying plant matter (Figure 17.24) .They

have two pairs of short legs per body segment. Centipedes are terrestrial

carnivores, with a pair of poison claws used in defense and to paralyze prey,

such as cockroaches and flies. Each of their body segments bears a single pair

of long legs.

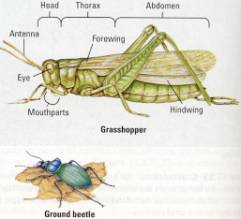

In species

diversity, insects outnumber all other forms of life combined. They live

in almost every terrestrial habitat and in fresh water, and flying insects fill

the air. Insects are rare, though not absent, in the seas, where crustaceans

are the dominant arthropods. There is a whole big branch of biology, called

entomology. that specializes in the study of insects.

The oldest insect

fossils date back to about 400 million years ago, during the Paleozoic era (see

Table 14.1). Later, the evolution of flight sparked an explosion in insect

variety (Figure 17.25). Like the grasshopper in Figure 17.25, most insects have

a three-part body: head, thorax, and abdomen. The head usually bears a pair of

sensory antennae and a pair of eyes. Several pairs of mouthparts are adapted

for particular kinds of eating-for example, for biting and chewing-plant

material in grasshoppers; for lapping up fluids in houseflies; and for piercing

skin and sucking blood in ! mosquitoes and other biting flies. Most adult

insects have three pairs of legs and one or two pairs of wings, all borne on

the thorax.

Flight is

obviously one key to the great success of insects. An animal that can fly can

escape many predators, find food and mates, and disperse to new habitats much

faster than an animal that must crawl about on the ground. Because their wings

are extensions of the exoskeleton and not true appendages, insects can fly

without sacrificing any walking legs. By contrast, the flying vertebrates-birds

and bats-have one of their two pairs of wa1king legs modified for wings, which

explains why these vertebrates are generally not very swift on the ground.

Figure 17.25 A small

sample of insect diversity

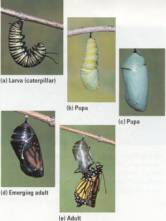

Figure 17.26 Metamorphosis

of a monarch butterfly. (a) The larva (caterpillar) spends its time eating and

growing, molting as it grows. (b) After several molts, the larva encases itself

in a cocoon and becomes a pupa. (c) Within the pupa, the larval organs break

down and adult organs develop from cells that were dormant in the larva. (d)

Finally, the adult emerges from the cocoon. (e) The butterfly flies off and

reproduces, nourished mainly from the calories it stored when it was a

caterpillar.

Many insects

undergo metamorphosis in their development. In the case of grasshoppers and some

other insect groups, the young resemble adults but are smaller and have

different body proportions. The animal goes through a series of molts, each

time looking more like an adult, until it reaches full size. In other cases,

insects have distinctive larval stages specialized for eating and growing that

are known by such names as maggots, grubs, or caterpillars. The larval stage

looks entirely different from the adult stage, which is specialized for

dispersal and reproduction. Metamorphosis from the larva to the adult occurs

during a pupal stage (Figure 17.26).

Animals so

numerous, diverse, and widespread as insects are bound to affect the lives of

all other terrestrial organisms, including humans. On one hand, we depend on

bees, flies, and many other insects to pollinate our crops and orchards. On the

other hand, insects are carriers of the micro-organisms that cause many

diseases, including malaria and African sleeping sickness. Insects also compete

with humans for food. In parts of Africa, for instance, insects claim about 75%

of the crops. Trying to minimize their losses, farmers in the United States

spend billions of dollars each year on pesticides, spraying crops with massive

doses of some of the deadliest poisons ever invented. Try as they may, not even

humans have challenged the preeminence of insects and their arthropod kin. As

Cornell University's Thomas Eisner puts it: "Bugs are not going to inherit

the Earth. They own it now. So we might as well make peace with the landlord:

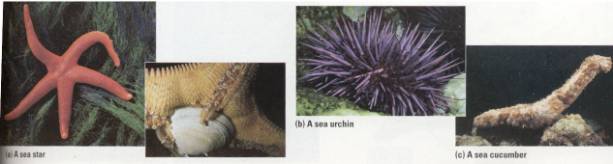

Echinoderms

The echinoderms

.(phylum Echinodermata) are named for their spiny surfaces. Sea urchins, the

porcupines of the invertebrates, are certainly echinoderms that live up to the

phylum name. Among the other echmoderms are sea stars, sand dollars, and sea

cucumbers (Figure 17.27). Echinoderms

are all marine. Most are sessile or slow moving. Echinoderms lack body

segments, and most have radial symmetry as adults. Both the external and the

internal parts of a sea star, for instance, radiate from the center like spokes

of a wheel. In contrast to the adult, the larval stage of echinoderms is

bilaterally symmetrical. This supports other evidence that echinoderms are not

closely related to cnidarians or other radial animals that never show bilateral

symmetry. Most echinoderms have an endoskeleton (interior skeleton) constructed

from hard plates just beneath the skin. Bumps and spines of this endoskeleton

account for the animal's rough or prickly surface. Unique to echinoderms is the

water vascular system, a network of water-filled canals that circulate water

throughout the echinoderm's body, facilitating gas exchange and waste disposal.

The water vascular system also branches into extensions called tube feet. A sea

star or sea urchin pulls itself slowly over the seafloor using its suction-

cup-like tube feet. Sea stars also use their tube feet to grip prey during

feeding (see Figure 17.27a).

Looking at sea

stars and other adult echinoderms, you may think they .have little in common

with humans and other vertebrates. But if you return to Figure 17.6, you'll see

that echinoderms share an evolutionary branch with chordates, the phylum that

includes vertebrates. Analysis of embryonic development reveals this

relationship. The mechanism of coelom formation and many other details of embryology

differentiate the echinoderms and chordates from the evolutionary branch that

includes mollusks, annelids, and arthropods. With this phylogenetic context,

we're now ready to make the transition from invertebrates to vertebrates.

Figure 17.27 Echinoderms. (a) The mouth of a sea star, not visible

here, is located in the center of the undersurface. The inset shows how the

tube feet function in feeding. When a sea star encounters an oyster or clam,

its favorite foods, it grips the mollusk's shell with its tube feet and

positions its mouth next to the narrow opening between the two halves of the

prey's shell. The sea star then pushes its stomach out through its mouth and

through the crack in the mollusk's shell. The predator then digests the soft

tissue of its prey. (b) In contrast to sea stars, sea urchins are spherical and

have no arms. If you look closely, you can see the long tube feet projecting

among the spines. Unlike sea stars, which are mostly carnivorous, sea urchins

mainly graze on seaweed and other algae. (c) On casual inspection, sea

cucumbers do not look much like other echinoderms. Sea cucumbers lack spines,

and the hard endoskeleton is much reduced. However, closer inspection reveals

many echinoderm traits, including five rows of tube feet.

The

vertebrate Genealogy

Most of us are curious about our

genealogy. On the personal level, we wonder about our family ancestry. As

biology students, we are interested in tracing human ancestry within the

broader scope of the entire animal kingdom. In this quest, we ask three

questions: What were our ancestors like? How are we related to other animals?

and What are our closest relatives?

Figure 17.28 Backbone, extra long. Vertebrates are named for their

backbone, which consists of a series of vertebrae. The vertebrate hallmark is

apparent in this snake skeleton. You can also see the skull, the bony case

protecting the brain. The backbone and skull are parts of an endoskeleton, a

skeleton inside the animal rather than covering it.

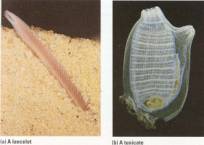

Figure 17.29 Invertebrate chordates. (a) lancelets owe their name

to their bladelike shape. Marine animals only a few centimeters long, lancelets

wiggle backward into sand, leaving only their head exposed. The animal filters

tiny food particles from the seawater. (b) This adult tunicate, or sea squirt,

is a sessile filter feeder that bears little resemblance to other chordates.

However, a tunicate goes through a larval stage that is unmistakably chordate.

Figure 17.30 Cordate

characteristics

In this section, we trace the evolution of

the vertebrates, the group that includes humans and their closest relatives.

Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and the various classes of fishes are all

classified as vertebrates. Among the unique vertebrate features are the cranium

and backbone, a series of vertebrae for which the group is named (Figure

17.28). Our first step in tracing the vertebrate genealogy is to determine

where vertebrates fit in the animal kingdom.

Characteristics

of Chordates

Vertebrates make

up one subphylum of the phylum Chordata. Our phylum also includes two subphyla

of invertebrates, animals lacking a backbone: lancelets and tunicates (Figure

17.29). These invertebrate chordates and vertebrates all share four key

features that appear in the embryo and sometimes in the adult. These four

chordate hallmarks are ( 1) a dorsal, hollow nerve cord ( the chordate brain

and spinal cord); (2) a notochord, which is a flexible, longitudinal rod

located between the digestive tract and the nerve cord; ( 3) pharyngeal slits,

which are gill structures in the pharynx, the region of the digestive tube just

behind the mouth; and ( 4) a post -anal tail, which is a tail to the rear of

the anus (Figure 17.30). Though these chordate characteristics are often

difficult to recognize in the adult animal, they are always present in chordate

embryos. For example, the notochord, for which our phylum is named, persists in

adult humans only in the form of the cartilage disks that function as cushions

between the vertebrae. (Back injuries described as "ruptured disks"

or "slipped disks" refer to these structures. )

Body segmentation

is another chordate characteristic, though not a unique one. The chordate

version of segmentation probably evolved independently of the segmentation we

observe in annelids and arthropods. Chordate segmentation is apparent in the

backbone of vertebrates (see Figure 17.28) and in the segmental muscles of all

chordates (see the chevron-shaped- »» -muscles in the lancelet of Figure

17.29a). Segmental musculature is not so obvious in adult humans unless one is

motivated enough to sculpture those washboard "abs of steel."

Vertebrates

retain the basic chordate characteristics, but have additional features that

are unique, including, of course, the backbone (see Figure 17.28). Figure 17.31

is an overview of chordate and vertebrate evolution that will provide a context

for our survey of the vertebrate classes.

Fishes

The first

vertebrates probably evolved during the early Cambrian period about 540 million

years ago. These early vertebrates, the agnathans, lacked jaws. Agnathans are

represented today by vertebrates called lampreys (see Figure 17.31). Some

lampreys are parasites that use their jawless mouths as suckers to attach to

the sides of large fishes and draw blood. In contrast, most vertebrates have

jaws, which are hinged skeletons that work the mouth. We know from the fossil

record that the first jawed vertebrates

were fishes that replaced most agnathans by about 400 million

years ago. In addition to jaws, these fishes had two pairs of fins, which made

them maneuverable swimmers. Some of those fishes were more than 10 m long.

Sporting jaws and fins, some of the early fishes were active predators that

could chase prey and bite off chunks of flesh. Even today, most fishes are

carnivores. The two major groups of living fishes are the class Chondrichthyes

( cartilaginous fishes-the sharks and rays) and the class Osteichthyes (the

bony fishes, including such familiar groups as tuna, trout, and goldfish).

Cartilaginous

fishes have a flexible skeleton made of cartilage. Most sharks are adept

predators-fast swimmers with streamlined bodies, acute senses, and powerful

jaws (Figure 17.]2a). A shark does not have keen eyesight, but its sense of

smell is very sharp. In addition, special electrosensors on the head can detect

minute electrical fields produced by muscle contractions in nearby animals.

Sharks also have a lateral line system. a row of sensory organs running along

each side of the body. Sensitive to changes in water pressure, the lateral line

system enables a shark to detect minor vibrations caused by animals swimming in

its neighborhood. There are fewer than 1,000 living species of cartilaginous

fishes, nearly all of them marine.

Bony fishes

(Figure 17.]2b) have a skeleton reinforced by hard calcium salts. They also

have a lateral line system, a keen sense of smell, and excellent eyesight. On

each side of the head, a protective flap called the operculwn (plural,

opercula) covers a chamber housing the gills. Movement of the operculum allows

the fish to breathe without swimming. (By contrast, sharks lack opercula and

must swim to pass water over their gills. ) Bony fishes also have a specialized

organ that helps keep them buoyant-the swim bladder. a gasfilled sac. Thus,

many bony fishes can conserve energy by remaining almost motionless, in

contrast to sharks, which sink to the bottom if they stop swimming. Some bony

fishes have a connection between the swim bladder and the digestive tract that

enables them to gulp air and extract oxygen from it when the dissolved oxygen

level in the water gets too low. In fact, swim bladders evolved from simple

lungs that augmented gills in absorbing oxygen from the water of stagnant

swamps, where the first bony fishes lived.

Figure 17.32 Two classes of fishes. (a) A member of the class

Chondrichthyes, the cartilaginous (b) A member of the class Osteichthyes, the

bony fishes.

The largest class

of vertebrates { about 30,000 species ), bony fishes are common in the seas and

in freshwater habitats. Most bony fishes, including trout, bass, perch, and

tuna, are ray-finned fishes. Their fins are supported by thin, flexible

skeletal rays (see Figure 17 .32b). A second evolutionary branch of bony fishes

includes the lungfishes and lobe-finned fishes. Lung-fishes live today in the

Southern Hemisphere. They inhabit stagnant ponds and swamps, surfacing to gulp

air into their lungs. The lobe-fins are named for their muscular fins supported

by stout bones. Lobe-fins are extinct except for one species, a deep-sea

dweller that may use its fins to waddle along the seafloor. Ancient freshwater

lobe-finned fishes with lungs played a key role in the evolution of amphibians,

the first terrestrial vertebrates.

Amphibians

In Greek, the,

word amphibios means "living a double life. Most members of the class

Amphibia exhibit a mixture of aquatic and terrestrial adaptations. Most species

are tied to water because their eggs, lacking shells, dry out quickly in the

air; The frog in Figure 17.33 spends much of its time on land, but it lays its

eggs in water. An egg develops into a larva called a tadpole, a legless,

aquatic algae-eater with gills, a lateral line system resembling that of

fishes, and a long finned tail. In changing into a frog, the tadpole undergoes

a radical metamorphosis. When a young frog crawls onto shore and begins life as

a terrestrial insect -eater, it has four legs, air-breathing lungs instead of

gills, a pair of external eardrums, and no lateral line system. Because of

metamorphosis, many amphibians truly live a double life. But even as adults,

amphibians are most abundant in damp habitats, such as swamps and rain forests.

This is partly because amphibians depend on their moist skin to supplement lung

function in exchanging gases with the environment. Thus, even those frogs that

are adapted to relatively dry habitats spend much of their time in humid

burrows or under piles of moist leaves. The amphibians of today, including

frogs and salamanders, account for only about 8% of all living vertebrates, or about

4,000 species.

Figure 17.33 The uduallifeu of an amphibian. Though not all

amphibians have aquatic larval stages. this class of vertebrates is named for

the familiar tadpole-to-frog metamorphosis of many species

Figure 17.34 The origin of tetrapods. Fossils of some lobe-finned

fishes have skeletal supports extending into their fins Early amphibians left

fossilized limb skeletons that probably functioned in movement on land

Amphibians were

the first vertebrates to colonize land. They descended from fishes that liad

lungs and fins with muscles and skeletal supports strong enough to enable some

movement, however clumsy, on land (Figure 17.34). The fossil record chronicles

the evolution of four-limbed amphibians from fishlike ancestors. Terrestrial vertebrates-amphibians,

reptiles, birds, and mammals-are collectively called tetrapods, which means

"four legs:' Had our amphibian ancestors had three pairs of legs on their

undersides instead of just two, we might be hexapods. This image seems silly,

but serves to reinforce the point that evolution, as descent with modification,

is constrained by history.

Reptiles

Class Reptilia

includes snakes, lizards, turtles, crocodiles, and alligators. The evolution of

reptiles from an amphibian ancestor paralleled many additional adaptations for

living on land. Scales containing a protein called keratin waterproof the skin

of a reptile, helping to prevent dehydration in dry air. Reptiles cannot

breathe through their dry skin and obtain most of their oxygen with their

lungs. Another breakthrough for living on land that evolved in reptiles is the

amniotic egg, a water-containing egg enclosed in a shell (Figure 17.35). The

amniotic egg functions as a "self -contained pond" that enables

reptiles to complete their life cycle on land. With adaptations such as

waterproof skin and amniotic eggs, reptiles broke their ancestral ties to

aquatic habitats. There are about 6,500 species of reptiles alive today.

Reptiles are

sometimes labeled "cold-blooded" animals because they do not use

their metabolism extensively to control body temperature. But reptiles do

regulate body temperature through behavioral adaptations. For example, many

lizards regulate their internal temperature by basking in the sun when the air

is cool and seeking shade when the air is too warm. Because they absorb

external heat rather than generating much of their own, reptiles are said to be

ectotherms, a term more accurate than cold-blooded. By heating directly with

solar energy rather than through the metabolic breakdown of food, a reptile can

survive on less than 10% of the calories required by a mammal of equivalent

size.

As successful as

reptiles are today, they were far more widespread, numerous, and diverse during

the Mesozoic era, which ,is sometimes called the "age of reptiles:'

Reptiles diversified extensively during that era, producing a dynasty that

lasted until the end of the Mesozoic, about 65 million years ago. Dinosaurs,

the most diverse group, included the largest animals ever to inhabit land. Some

were gentle giants that lumbered about while browsing vegetation. Others were

voracious carnivores that chased their larger prey on two legs (Figure 17.36).

Figure 17.35 Terrestrial equipment of reptiles. This bull snake

displays two reptilian adaptations to living on land: a waterproof skin with

keratinized scales; and amniotic eggs, with shells that protect a watery,

nutritious internal environment where the embryo can develop on land. Snakes

evolved from lizards that adapted to a burrowing lifestyle.

Figure 17.36 A Mesozoic feeding frenzy. Hunting in packs, Deinonychus (meaning "terrible claw")

probably used its sickle-shaped claws to slash at larger prey.

Figure 17.37 A bald eagle in flight. Bird wings are airfoils,

which have shapes that create lift by altering air currents. Air passing over a

wing must travel farther in the same amount of time than air passing under the

wing. This expands the air above the wing relative to the-air below the wing.

And this makes the air pressure pushing upward against the lower wing surface

greater than the pressure of the expanded air pushing downward on the wing. The

wings of birds and airplanes owe their "lift" to this pressure

differential.

The age of reptiles began to wane about 70

million years ago. During the Cretaceous, the last period of the Mesozoic era,

global climate became cooler and more variable. This was a period of mass

extinctions that claimed all the dinosaurs by about 65 million years ago,

except for one lineage. That lone surviving lineage is represented today by

birds.

Birds

Birds (class

Aves)evolved during the great reptilian radiation of the Mesozoic era. Amniotic eggs and scales on the legs

are just two of the reptilian features

we see in birds. But modern birds look quite different from modern reptiles

because of their feathers and other distinctive flight equipment. Almost all of

the 8,600 living bird species are airborne. The few flightless species,

including the ostrich, evolved from flying ancestors. Appreciating the avian

world is all about understanding flight.

Almost every

element of bird anatomy is modified in some way that enhances flight. The bones

have a honeycombed structure that makes them strong but light ( the wings of

airplanes have the same basic construction).

For example, a huge seagoing species called the frigate bird has a

wingspan of more than 2 m, but its whole skeleton weighs only about 113 g (4

ounces). Another adaptation that reduces the weight of birds is the absence of

some internal organs found in other vertebrates. Female birds, for instance,

have only one ovary instead of a pair. Also, modern birds are toothless, an

adaptation that trims the weight of the head (no uncontrolled nosedives). Birds

do not chew food in the mouth but grind it in the gizzard, a chamber of the

digestive tract near the stomach.

Flying requires a

great expenditure of energy and an active metabolism. In contrast to the

ectothermic reptiles, birds are endotherms. That means they use their own

metabolic heat to maintain a warm, constant body temperature. A bird's most

obvious flight equipment is its wings. Bird wings are air-foils that illustrate

the same principles of aerodynamics as the wings of an airplane (Figure 17.37).

A bird's flight motors are its powerful breast muscles, which are anchored to a

keel-like breastbone. It is mainly these flight muscles that we call

"white meat" on a turkey or chicken. Some birds, such as eagles and

hawks, have wings adapted for soaring on air currents and flap their wings only

occasionally. Other birds, including hummingbirds, excel at maneuvering but

must flap continuously to stay aloft. In either case, it is the shape and

arrangement of the feathers that form the wing into an air-foil. Feathers are

made of keratin, the same protein that forms our hair and fingernails as well

as the scales of reptiles. Feathers may have functioned first as insulation,

helping birds retain body heat, only later being co-opted as flight gear.

In tracing the

ancestry of birds back to the Mesozoic era, we must search for the oldest

fossils with feathered wings that could have the functioned in flight. Fossils

of an ancient bird named Archaeopteryx have been found in Bavarian limestone in

Germany and date back some 150 million years into the dinosaurs, birds, and

Jurassic period (see Figure 14.15). Archaeopteryx is not considered the

ancestor of modern birds, and paleontologists place it on a side branch of the

avian linage Nonetheless, Archaeopteryx probably was derived from ancestral

forms that also gave rise to modern birds. Its skeletal anatomy indicates that

it was a weak flyer, perhaps mainly a tree-dwelling glider. A combination of

gliding downward and jumping into the air from the ground may have been the

earliest mode of flying in the bird lineage.

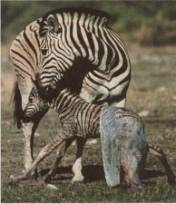

Figure 17.38 The three major groups of mammals. (a) Monotremes,

such as this echidna, are the only mammals that lay eggs (inset). (b) The young

of marsupials, such as this brushtail opossum, are born very early in their

development. They finish their growth while nursing from a nipple in their

mother's pouch. (c) In eutherians (placentals), such as these zebras, young

develop within the uterus of the mother. There they are nurtured by the flow of

blood though the dense network of vessels in the placenta. The reddish portion

of the afterbirth clinging to the newborn zebra in this photograph is the

placenta. (see prior)

Mammals

Mammals (class

Mammalia) evolved from reptiles about 225 million years ago, long before there

were any dinosaurs. During the peak of the age of reptiles, there were a number

of mouse-sized, nocturnal mammals that lived on a diet of insects. Mammals

became much more diverse after the downfall of the dinosaurs. Most mammals are

terrestrial. However, there are nearly 1,000 species of winged mammals, the

bats. And about 80 species of dolphins, porpoises, and whales are totally

aquatic. The blue whale, an endangered species that grows to lengths of nearly

30 m, is the largest animal that has ever existed.

Two features-hair

and mammary glands that produce milk that nourishes the young-are mammalian

hallmarks. The main function of hair is to insulate the body and help maintain

a warm, constant internal temperature; mammals, like birds, are endotherms.

There are three major groups of mammals: the monotremes, the marsupials, and

theeutherians. The duck-billed platypus is one of only threeexisting species of

monotremes, the egg-laying mammals. The platypus lives along rivers in eastern

Australia and on the nearby island of Tasmania. It eats mainly small shrimps

and aquatic insects. The female usually lays two eggs and incubates them in a

leaf nest. After hatching, the young nurse by licking up milk secreted onto the

mother's fur. The animals called echidnas are also monotremes (Figure 17.38a).

Most mammals are

born rather than hatched. During gestation in marsupials and eutherians, the

embryos are nurtured inside the mother by an organ called the placenta.

Consisting of both embryonic and maternal tissues, the placenta joins the

embryo to the mother within the uterus. The embryo is nurtured by maternal

blood that flows close to the embryonic blood system in the placenta. The

embryo is bathed in fluid contained by an amniotic sac, which is homologous to

the fluid compartment within the amniotic eggs of reptiles.

Marsupials are

the so-called pouched mammals, including kangaroos and koalas. These mammals

have a brief gestation and give birth to tiny, embryonic offspring that

complete development while attached to the mother's nipples. The nursing young

are usually housed in an external pouch, called the marsupium, on the mother's

abdomen (Figure 17.38b ). Nearly all marsupials live in Australia, New Zealand,

and Central and South America. Australia has been a marsupial sanctuary for

much of the past 60 million years. Australian marsupials have diversified

extensively, filling terrestrial habitats that on other continents are occupied

by eutherian mammals.

Eutherians are

also called placental mammals because their placentas provide more intimate and

long-lasting association between the mother and her developing young than do

marsupial placentas (Figure 17.38c ) .Eutherians make up almost 95% of the

4,500 species of living mammals. Dogs, cats, cows, rodents, rabbits, bats, and

whales are all examples of eutherian mammals. One of the eutherian groups is

the order Primates, includes monkeys, apes, and humans.

Figure 17.39 The arboreal athleticism of primates. This orangutan

displays primate adaptations for living in the trees: limber shoulder joints,

manual dexterity, and stereo vision due to eyes on the front of the face.

The

Human Ancestry

We have now traced the animal genealogy to

the mammalian group that includes Homo sapiens and its closest kin. We are

primates. To understand .what that means, we must trace our ancestry back to

the trees, where some of our most treasured traits originated as arboreal

adaptations.

The

Evolution of Primates

Primate evolution provides a context for

understanding human origins. The fossil record supports the hypothesis that

primates evolved from insect-eating mammals during the late Cretaceous period,

about 65 million years ago. Those early primates were small, arboreal {

tree-dwelling) mammals. Thus, the order

Primates was first distinguished by characteristics that were shaped, through

natural selection, by the demands of living in the trees. For example, primates have limber shoulder

joints, which make it possible to brachiate {swing from one branch to another).

The dexterous hands of primates can hang on to branches and manipulate food.

Nails have replaced claws in many primate species, and the fingers are very

sensitive. The eyes of primates are close together on the front of the face.

The overlapping fields of vision of the two eyes enhance depth perception, an

obvious advantage when brachiating. Excellent eye-hand coordination is also

important for arboreal maneuvering {Figure 17.39). Parental care is essential

for young animals in the trees. Mammals devote more energy to caring for their

young than most other vertebrates, and primates are among the most attentive

parents of all mammals. Most primates have single births and nurture their

offspring for a long time. Though humans do not live in trees, we retain in

modified form many of the traits that originated there.

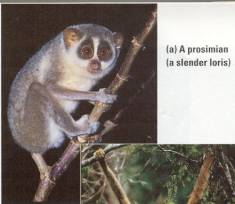

Taxonomists divide the primates into twp

main groups: prosimians and anthropoids. The oldest primate fossils are

prosimians. Modern prosimians include the lemurs of Madagascar and the lorises,

pottos, and tarsiers that live in tropical Africa and southern Asia (Figure

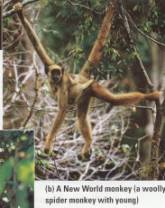

17.40a). Anthropoids include monkeys, apes, and humans. All monkeys in the New

World ( the Americas) are arboreal and are distinguished by prehensile tails

that function as an extra appendage for brachiating (Figure 17.40b). (If you

see a monkey in a zoo swinging by its tail, you know it's from the New World. )

Although some Old World monkeys are also arboreal, their tails are not

prehensile. And many Old World monkeys, including baboons, macaques, and

mandrills, are mainly ground-dwellers (Figure 17.40c).

Figure

17.40 Primate diversity (a) A

prosimian. (b) – (c) Monkeys (d) – (g) Apes

(h) human

Our closest

anthropoid relatives are the apes: gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, and

chimpanzees (Figure 17.40d-g). Modern apes live only in tropical regions of the

Old World. With the exception of some gibbons, apes are larger than monkeys,

with relatively long arms and short legs and no tail. Although all the apes are capable of brachiation,

only gibbons and orangutans are primarily arboreal. Gorillas and chimpanzees

are highly social. Apes have larger brains proportionate to body size than

monkeys, an their behavior is consequently more adaptable.

The Emergence of Humankind

Humanity

is one very young twig on the vertebrate branch, just one of many branches on

the tree of life. In the continuum of life spanning 3.5 billion years, humans

and apes have shared a common ancestry for all but the last 5-7 million years

(Figure 17.41 ). Put another way, if we compressed the history of life to a

year, humans and chimpanzees diverged from a common ancestor less than 18 hours

ago. The fossil record and molecular systematics concur in that vintage for the

human lineage. Paleoanthropology, the study of human evolution, focuses on this

very thin slice of biological history. Some Common Misconceptions Certain

misconceptions about human evolution that were generated during the early part

of the twentieth century still persist today in the minds of many, long after

these myths have been debunked by the fossil evidence.

Figure

17.41 Primary Phylogeny

Let's first

dispose of the myth that our ancestors were chimpanzees or any other modern

apes. Chimpanzees and humans represent two divergent branches of the anthropoid

tree that evolved from a common, less specialized ancestor. Chimps are not our

parent species, but more like our phylogenetic siblings or cousins.

Another

misconception envisions human evolution as a ladder with a series of steps

leading directly from an ancestral anthropoid to Homo sapiens. This is often

illustrated as a parade of fossil hominids (members of the human family)

becoming progressively more modern as they march across the page. If human

evolution is a parade, then it is a disorderly one, with many splinter groups

having traveled down dead ends. At times in hominid history, several different

human species coexisted (Figure 17.42). Human phylogeny is more like a

multibranched bush than a ladder, with our species being the tip of the only

twig that still lives.

One more myth we

must bury is the notion that various human characteristics, such as upright

posture and an enlarged brain, evolved in unison. A popular image is of early

humans as half-stooped, half-witted cave-dwellers. In fact, we know from the fossil record that different human features

evolved at different rates, with erect posture, or bipedalism, leading the way.

Our pedigree includes ancestors who walked upright but had ape-sized brains.

After dismissing some of the folklore on human evolution, however, we must

admit that many questions about our ancestry have not yet been

resolved.

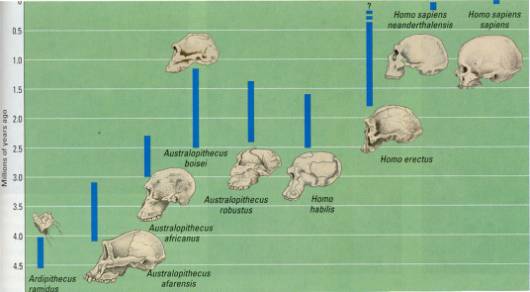

Figure 17.42 A timeline of human evolution. Notice that there have been times when two

or more hominid species coexisted. The skulls are all drawn to the same scale

enable you to compare the sizes of craniums and hence brain

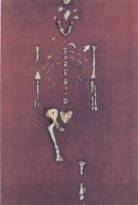

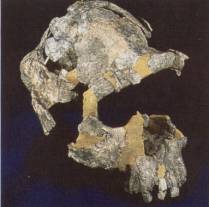

Figure 17.43 The antiquity of upright posture. (a) Lucy, a

3.18-million-year-old skeleton, represents the hominid species Australopithecus

afarensis. Fragments of the pelvis and skull put A. afarensis on two feet. (b)

Some 3.7 million years ago, several bipedal (upright-walking) hominids left

footprints in damp volcanic ash in what is now Tanzania in East Africa. The

prints fossilized and were discovered by British anthropologist Mary Leakey in

1978. The footprints are part of the strong evidence that bipedalism is a vefry

old human trait. (c) This A afarensis

skull, 3.9 million years old, articulated with a vertical back bone. The

upright posture of humans is a least that old.

Australopithecus

and the Antiquity of Bipedalism Before there was Homo, several hominid

species of the genus Australopithecus walked the African savanna (grasslands

with clumps of trees ). Paleoanthropologists have focused much of their

attention on A. afarensis, an early species of Australopithecus. Fossil

evidence now pushes bipedalism in A. afarensis back to at least 4 million years

ago (Figure 17.43) .Doubt remains whether an even older hominid, Ardipithecus

ramidus, which dates back at least 4.4 million years, was bipedal.

One of the most

complete fossil skeletons of A. afarensis dates to about 3.2 million years ago

in East Africa. Nicknamed Lucy by her discoverers, the individual was a female,

only about 3 feet tall, with a head about the size of a softball (see Figure

17.43a). Lucy and her kind lived in savanna areas and may have subsisted on

nuts and seeds, bird eggs, and whatever animals they could catch or scavenge

from kills made by more efficient predators such as large cats and dogs.

All

Australopithecus species were extinct by about 1.4 million years ago. Some of

the later species overlapped in time with early species of our own genus, Homo

( see Figure 17.42 ) .Much debate centers on the evolutionary relationships of

the Australopithecus species to each other and to Homo. Were the Australopithecus

species all evolutionary side branches? Or were some of them ancestors to later

humans? Either way, these early hominids show us that th~ fundamental human

trait ofbipedalism evolved millions of years before the other major human

trait-an enlarged brain. As evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould put it,

"Mankind stood up first and got smart later”.

Homo habilis

and the Evolution of Inventive Minds Enlargement of the human brain is

first evident in fossils from East Africa dating to the latter part of the era

of Australopithecus, about 2.5 million years ago. Anthropologists have

found skulls with brain capacities intermediate in size between those of the

latest Australopithecus species and those of Homo sapiens. Simple handmade

stone tools are sometimes found with the larger-brained fossils, which have

been dubbed Homo habilis ("handy man"). After walking upright for

about 2 million years, humans were finally beginning to use their manual

dexterity and big brains to invent tools that enhanced their hunting,

gathering, and scavenging on the African savanna.

Homo erectus and the

Global Dispersal of Humanity The first species to extend humanity's