H-Evolution-002

Molecular Biology

Preface

Interest in how nature

replicates began when working with Dr Ken O’Kief of TRW. TRW was tech advisor to AF for the Minuteman

missile program, when I worked for Autonetics division of Rockwell, who built

Guidance and Control systems for that series.

Our work on Post Boost Rocket Engine System had ended and I was out of a

job. I suggested we should determine

how to convert analog controls to digital, and was asked to pursue the

concept. With great difficulty I

developed a digital signal processor that could serve all stages by being programmable. Our companies arranged for Ken and I to work

together on pending concepts. When we

broke for lunch Ken said this is not a signal processor but a programmable

computer, setting the stage for his

question when we returned: “could you

design a computer that could replicate itself?” My thoughts focused on how to automate making the “digital

computer” we’d been discussing. After a

few minutes thought I said, “no, there is no way to automate supply of

parts.” The with a slight smile Ken

said “I’m looking at one.” It took a

moment to realized what he had just said.

We humans are computers that

replicate!!. I had been taking a

night class in Biology and at lunch told Ken of a booklet describing the DNA

molecule and text book “Molecular Biology” by Watson, which prompted his question.

I kept pondering how nature solves the supply problem? When observing contaminate moving in a pool,

I said, that’s it. Life began in the

oceans, a sea of molecular soup, kept in constant motion. The DNA code that evolved was immersed in

it’s part supply, combining parts by magnetic attraction per patterns that

survived.

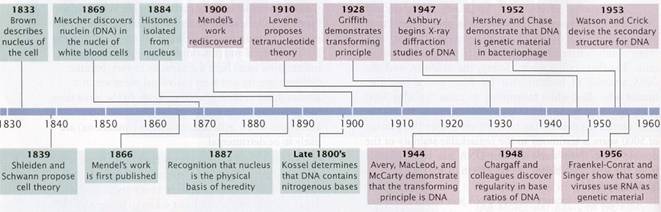

Many contributed to our understanding of genetics

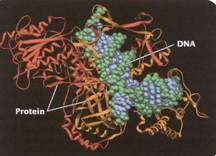

Protein Structure: When a cell makes a polypeptide, the chain

usually folds spontaneously to form the functional shape for that protein (a

biological polymer constructed from amino acid monomers.). It is a protein's

three-dimensional shape that enables the molecule to carry out its specific

function in a cell. In almost every case, a protein's function depends on its

ability to recognize and bind to some other molecule. For example, the

receptors on the brain cell below are actually proteins that recognize certain

chemical signals from other cells. If the protein receptor's shape were to be

altered, then it would not be able to perform this recognition function. With

proteins, function follows form -- that is, what a protein does is a

consequence of its shape.

Proteins come in a variety of kinds and

packages, they are the supply source when building cells from DNA & RNA

patterns.

A

protein's shape is sensitive to the surrounding environment. An unfavorable

change in temperature, pH, or some other quality of the aqueous environment can

cause a protein to unravel and lose its normal shape. This is called

denaturation of the protein.

Given an

environment suitable for that protein (so that it doesn't denature), the

primary structure of a protein causes it to fold into its functional shape.

Each kind of protein has a unique primary structure and therefore a unique

shape that enables it to do a certain job in a cell. Each polypeptide chain has a sequence specified by an inherited

gene.

Nucleic

Acids

Nucleic acids

are information storage molecules that provide the directions for building

proteins. The name nucleic comes from their location in the nuclei of

eukaryotic cells. There are actually two types of nucleic acids: DNA (those

most famous of chemical initials, which stand for deoxyribonucleic acid) and

RNA (for ribonucleic acid). The genetic material that humans and other

organisms inherit from their parents consists of giant molecules of DNA. Within

the DNA are genes, specific stretches of DNA that program the amino acid

sequences (primary structure) of proteins. Those programmed instructions,

however, are written in a kind of chemical code that must be translated

from "nucleic acid language" to "protein language."

A cell's RNA molecules help translate.

Nucleic acids are

polymers of monomers called nucleotides (Figure 3.24). Each nucleotide is

itself a complex organic molecule with three parts. At the center of each

nucleotide is a five-carbon sugar, deoxyribose in DNA and ribose in RNA. Attached

to the sugar is a negatively charged phosphate group containing a phosphorus

atom bonded to oxygen atoms (PO4-). Also attached to the sugar is a

nitrogen-containing base (nitrogenous base) made of one or two rings. (It is

called a base because it behaves like a base, or alkali, in aqueous solutions.)

The sugar and phosphate are the same in all nucleotides; only the base varies.

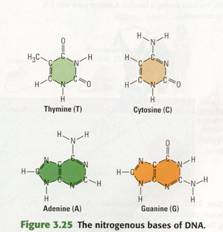

Each DNA nucleotide has one of the following four bases: adenine (abbreviated

A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), or thymine (T). Thus, all genetic information is

written in a four-letter alphabet-A, G, C, T -the bases that distinguish the

four nucleotides that make up DNA

(Figure 3.25).

Nucleotide monomers are linked into long

chains called polynucleotides, or DNA strands (Figure 3.26a). Nucleotides are

joined together by covalent .bonds between the sugar of one nucleotide and the

phosphate of the next. This results in a sugar-phosphate backbone, a repeating

pattern of sugar-phosphate-sugar-phosphate, with the bases hanging off the backbone

like appendages. Polynucleotides vary in length from long to very long, so the

number of possible polynucleotide sequences is very great. One long DNA strand

contains many genes, each a specific series of hundreds or thousands of

nucleotides. And each of these genes stores information in its unique sequence

of nucleotide bases. In fact, it is this information that cells translate into

an amino acid sequence to make a specific protein.

How can the cells of parents copy their

genes to pass along to offspring? Inheritance is based on DNA actually being

double-stranded, with the two DNA strands wrapped around each other to form a

double helix. In the central core of the helix, the bases along one DNA strand

hydrogen-bond to bases along the other strand. This base pairing is specific:

The base A can pair only with T, and G can pair only with C. Thus, if you know

the sequence of bases along one DNA strand, you also know the sequence along

the complementary strand in the double helix. This unique base pairing is the

basis of DNA’s ability to act as the molecule of inheritance.

What about RNA? As its name-ribonucleic

acid-implies, its sugar is ribose rather than deoxyribose. By comparing the RNA

nucleotide in, Figure 3.27 with the DNA nucleotide in Figure 3.24 you can see

that the RNA ribose sugar has an extra -OH group compared with the DNA

deoxyribose sugar (deoxy means "without an oxygen"). Another

difference between RNA and DNA is that instead of the base thymine, RNA has a

similar but distinct base called uracil (U). Except for the presence of ribose

and uracil, an RNA polynucleotide chain is identical to a DNA polynucleotide

chain. However, RNA is usually found only in a single-stranded form, while

DNA usually exists as a double helix.

Figure

10-2

Figure 10.2 The structure of a DNA

polynucleotide. A molecule of DNA contains two polynucleotides, each a chain of

nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of a nitrogenous base, a sugar (blue),

and a phosphate group (gold). The nucleotides are linked, the sugar of one

connected to the phosphate of the next, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone,

with the bases protruding from the sugars. The chemical structure at the right

shows the details of a DNA nucleotide. The sugar has five carbon atoms (shown

in red for emphasis) and is called deoxyribose. The phosphate group has given

up an H+ ion, acting as an acid. Hence, the full name for DNA is

deoxyribonucleic acid.

The Structure and Replication of DNA

DNA was known as a chemical in cells by

the end of the nineteenth century, but Mendel and other early geneticists did

all their work without any know-ledge of DNA’s role in heredity. By the late

1930s, experimental studies had convinced most biologists that a specific kind

of molecule, rather than some complex chemical mixture, was the basis of

inheritance. Attention focused on

chromosomes, which were already known to carry genes. By the 1940s, scientists

knew that chromosomes consisted of two types of chemicals: DNA and protein. And

by the early 1950s, a series of discoveries had convinced the scientific world

that DNA was the hereditary material.

What came next was one of the most

celebrated quests in the history of science -- the effort to figure out the

structure of DNA. A good deal was already known about DNA. Scientists had

identified all its atoms and knew how they were covalently bonded to one

another. What was not understood was the specific arrangement that gave DNA its

unique properties – the capacity to store genetic information, copy it, and

pass it - from generation to generation. A race was on to discover how the

structure of this molecule could account for its role in heredity. We will

describe that momentous discovery shortly. First, look at the underlying

chemical structure of DNA and its chemical cousin RNA.

DNA

and RNA: Polymers of Nucleotides I

Both DNA and RNA are nucleic acids, which

consist of long chains (polymers) of chemical units (monomers) called

nucleotides. (Figures 3.25-3.27.) A very simple diagram of a nucleotide

polymer, or polynucleotide, is shown on the left in Figure 10.2. This sample

polynucleotide chain shows only one possible arrangement of the four different

types of nucleotides ( abbreviated A, C, T and G) that make up DNA.

Polynucleotides tend to be very long and can have any sequence of nucleotides,

so a great number of polynucleotide chains are possible.

The nucleotides are joined to one another

by covalent bonds between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the

next. This results in a sugar-phosphate backbone, a repeating pattern of

sugar-phosphate-sugar-phosphate. The nitrogenous bases are arranged like

appendages along this backbone. Zooming in on our polynucleotide in Figure

10.2, we see that each nucleotide consists of three components: a nitrogenous

base, a sugar (blue), and a phosphate group (gold). Examining a single

nucleotide even more closely (Figure 10.2), we see the chemical structure of

its three components. The phosphate group, with a phosphorus atom (P) at its

center, is the source of the acid in nucleic acid. (The phosphate has given up

a hydrogen ion, H+ , leaving a negative charge on one of its oxygen atoms.) The

sugar has five carbon atoms: four in its ring and one extending above the ring.

The ring also includes an oxygen atom. The sugar is called deoxyribose because,

compared to the sugar ribose, it is missing an oxygen atom. The full name for

DNA is deoxyribonucleic acid, with the nucleic part coming from DNA’s location

in the nuclei of eukaryotic cells. (some, mDNA, is located in the

mitochondria.) The nitrogenous base ( thymine, in our example) has a ring of

nitrogen and carbon atoms with various functional groups attached. In contrast

to the acidic phosphate group, nitrogenous bases are basic; hence their name.

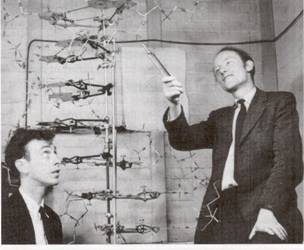

Figure 10.3 Co discoverers

Watson & Crick

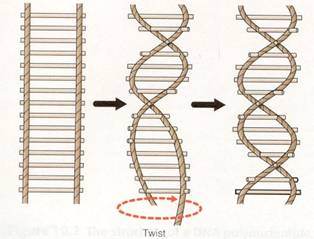

Figure 10.4 A rope-ladder

model of a double helix. The ropes at the sides represent the sugar-phosphate

backbones. Each wooden rung stands for a pair of bases connected by hydrogen

bonds.

The four nucleotides found in DNA differ

only in their nitrogenous bases (Figure 3.25). At this point, the structural

details are not as important as the fact that the bases are of two types. Thymine

(T) and cytosine (C) are single-ring structures. Adenme (A)

and guanme (G) are larger, double-ring structures. (The one-letter

abbreviations can be used for either the bases alone or for the nucleotides

containing them.) Recall that RNA has the nitrogenous base uracil (U)

instead of thymine ( uracil is very similar to thymine). RNA also contains a

slightly different sugar than DNA (ribose instead of deoxyribose). Other than

that, RNA and DNA polynucleotides have the same chemical structure.

Watson

and Crick's Discovery of the Double Helix

The celebrated partnership that resulted

in the determination of the physical structure of DNA began soon after a

23-year-old American named James D. Watson journeyed to Cambridge University,

where Englishman Francis Crick was studying protein structure with a technique

called X-ray crystallography . While visiting the laboratory of Maurice Wilkins

at King's College in London, Watson saw an X-ray crystallographic photograph of

DNA, produced by Wilkins's colleague Rosalind Franklin. The photograph clearly

revealed the basic shape of DNA to be a helix (spiral). On the basis of

Watson's later recollection of the photo, he and Crick deduced that the

diameter of the helix was uniform. The thickness of the helix suggested that it

was made up of two polynucleotide strands-in other words, a double helix.

Using wire models, Watson and Crick began

trying to construct a double helix that would conform both to Franklin's data

and to what was then known about the chemistry of DNA. After failing to make a

satisfactory model that placed the sugar-phosphate backbones inside the double

helix, Watson tried putting the backbones on the outside and forcing the

nitrogenous bases to swivel to the interior of the molecule. It occurred to him

that the four kinds of bases might pair in a specific way. This idea of

specific base pairing was a flash of inspiration that enabled Watson and Crick

to solve the DNA puzzle.

At first, Watson imagined that the bases

paired like with like - for example A with A, C with C. But that kind of

pairing did not fit with the fact

Figure

10.5

Figure 10.5 Three representations of DNA. (a) In this model, the

sugar-phosphate backbones are blue ribbons, and the bases are complementary

shapes in shades of green and orange. (b) In this more chemically detailed

structure, you can see the individual hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). You can

also see that the strands run in opposite directions; notice that the sugars on

the two strands are upside down with respect to each other. (c) In this

computer graphic of a DNA double helix, each atom is shown as a sphere,

creating a space-filling model, that the DNA molecule was a uniform diameter.

In AA pair (made of double-ringed bases) would be almost twice as wide as a CC

pair (made of single-ringed bases), causing bulges in the molecule. It soon

became apparent that a double-ringed base on one strand must always be paired

with a single-ringed base on the opposite strand. Moreover, Watson and Crick

realized that the individual structures of the bases dictated the pairings even

more specifically. Each base has chemical side groups that can best form

hydrogen bonds with one appropriate partner ( to review the hydrogen bond, see

Figure 2.11). Adenine can best form hydrogen bonds with thymine, and guanine

with cytosine. In the biologist's shorthand, A pairs with T, and G pairs with

C. A is also said to be "complementary" to T, and G to C.

You can picture the model of the DNA

double helix proposed by Watson and Crick as a rope ladder having rigid, wooden

rungs, with the ladder twisted into a spiral (Figure 10.4). Figure 10.5 shows

three more detailed representations of the double helix. The ribbon like

diagram in Figure 10.5a symbolizes the models of the bases with shapes that

emphasize their complementarity. Figure 10.5b is a more chemically precise

version showing only four base pairs, with the helix untwisted and the

individual hydrogen bonds specified by dashed lines; you can see that the

double helix has an antiparallel arrangement-that is, the two sugar-phosphate

backbones are oriented in opposite directions. Figure 10.5c is a computer

graphic showing every atom of part of a double helix.

Although the base-pairing rules dictate

the side-by-side combinations nitrogenous bases that form the rungs of the

double helix, they place no restrictions on the sequence of nucleotides along

the length of a DNA strand. In fact, the sequence of bases can vary in

countless ways.

In April 1953, Watson and Crick shook the

scientific world with a succinct, two-page announcement of their molecular

model for DNA in the journal Nature. Few milestones in the history of biology

have had as broad an impact as their double helix, with its AT and CG base

pairing. In 1962, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the Nobel Prize for their

work. {Franklin may have received the prize as well, had she not died from

cancer in 1958.)

In their 1953 paper, Watson and Crick

wrote that the structure they proposed "immediately suggests a possible

copying mechanism for the genetic material." In other words, the structure

of DNA also points toward a molecular explanation for life's unique properties

of reproduction and inheritance, as we see next.

DNA

Replication

When a cell or a whole organism

reproduces, a complete set of genetic instructions must pass from one

generation to the next. For this to occur, there must be a means of copying the

instructions. Watson and Crick's model for DNA structure immediately suggested

to them that DNA replicates by a template mechanism-each DNA strand can

serve as a mold, or template, to guide reproduction of the other strand.

The logic behind the Watson-Crick proposal for how DNA is copied is quite

simple. If you know the sequence of bases in one strand of the double helix,

you can very easily determine the sequence of bases in the other strand by

applying the base-pairing rules: A pairs with T (and T with A), and G pairs

with C (and C with G). For example, if one polynucleotide has the sequence

ATCG, then the complementary polynucleotide in that DNA molecule must have the

sequence TAGC.

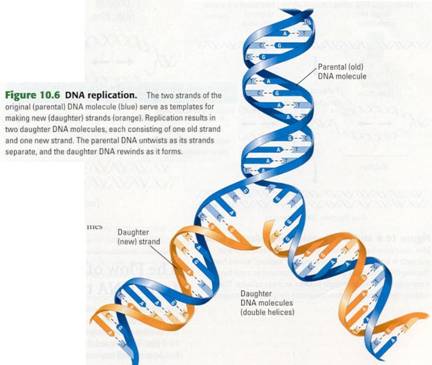

Figure 10.6 shows how the template model

can account for the direct copying of a piece of DNA. The two strands of

parental DNA separate, and each becomes a template for the assembly of a

complementary strand from a supply of free nucleotides. The nucleotides are

lined up one at a time along the template strand in accordance with the

base-pairing rules. Enzymes link the nucleotides to form the new DNA strands.

The completed new molecules, identical to the parental molecule, are known as

daughter DNA molecules (no gender should be inferred from this name).

Although the general mechanism of DNA replication

is conceptually simple, the actual process is complex and requires the

cooperation of more than a dozen enzymes and other proteins. The enzymes that

actually make the covalent bonds between the nucleotides of a new DNA strand

are called DNA polymerases. As an incoming nucleotide base-pairs with

its complement on the template strand, a DNA polymerase adds it to the end of

the growing daughter strand (polymer ). The process is both fast and

amazingly accurate; typically, DNA replication proceeds at a rate of 50

nucleotides per second, with only about one in a billion incorrectly

paired. (This is like parallel signal processing) In addition to their

roles in DNA replication, DNA polymerases and some of the associated proteins

are also involved in repairing damaged DNA. DNA can be harmed by toxic

chemicals in the environment or by high-energy radiation, such as X-rays and

ultraviolet light

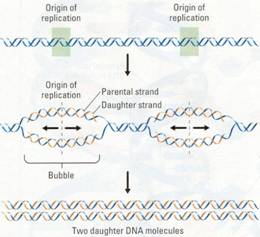

DNA replication begins at specific sites

on a double helix, called origins of replication. It then proceeds in both

directions, creating what are called replication "bubbles" (Figure

10.8). The parental DNA strands open up as daughter strands elongate on both

sides of each bubble. The DNA molecule of a eukaryotic chromosome has many

origins where replication can start simultaneously, shortening the total time

needed for the process. Eventually, all the bubbles merge, yielding two

completed double-stranded daughter DNA molecules.

DNA replication ensures that all the

somatic cells in a multicellular organism carry the same genetic information.

It is also the means by which genetic instructions are copied for the next

generation of the organism.

How

an Organism's DNA Genotype Produces Its Phenotype

Knowing the structure of DNA, we can now

define genotype (genetic makeup) and phenotype (the

expressed traits of an organism) more precisely. An organism's genotype is the sequence of nucleotide bases in its

DNA. The molecular basis of the phenotype lies in proteins with a variety of

functions. For example, structural proteins help make up the body of an

organism, and enzymes catalyze its metabolic activities. What is the connection

between the genotype and the protein molecules that more directly determine the

phenotype? Recall that DNA specifies the synthesis of proteins. A gene does

not build a protein directly, but rather dispatches instructions in the form of

RNA, which in turn programs protein synthesis. This central concept in

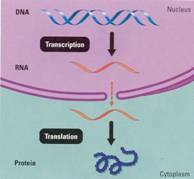

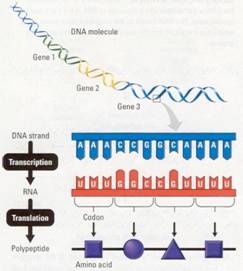

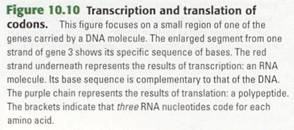

biology is summarized in Figure 10.9. The chain of command is from DNA in the

nucleus of the cell to RNA to protein synthesis in the cytoplasm (the parts

supply) . The two main stages are transcription, the transfer of genetic

information from DNA into an RNA molecule, and translation, the transfer

of the information in the RNA into a protein.

The relationship between genes and

proteins was first proposed in 1909, when English physician Archibald Garrod

suggested that genes dictate phenotypes through enzymes, the proteins that

catalyze chemical processes. Garrod's idea came from his observations of

inherited diseases. He hypothesized that an inherited disease reflects a

person's inability to make a particular enzyme, and he referred to such

diseases as "inborn errors of metabolism." He gave as one example the

hereditary condition called alkaptonuria, in which the urine appears dark red

because it contains a chemical called alkapton. Garrod reasoned that normal

individuals have an enzyme that breaks down alkapton, whereas alkaptonuric

individuals lack the enzyme. Garrod's hypothesis was ahead of its time, but

research conducted decades later proved him right. In the intervening years,

biochemists accumulated evidence that cells make and break down biologically

important molecules via metabolic pathways, as in the synthesis of an amino

acid or the breakdown of a sugar. Each step in a metabolic pathway is catalyzed

by a specific enzyme. If a person lacks one of the enzymes, the pathway cannot

be completed.

The major breakthrough in demonstrating

the relationship between genes and enzymes came in the 1940s from the work of

American geneticists George Beadle and Edward Tatum with the orange bread mold

Neurospora crassa. Beadle and Tatum studied strains of the mold that were

unable to grow on the usual simple growth medium. Each of these strains turned out to lack an enzyme in a metabolic

pathway that produced some molecule the mold needed such as an amino acid.

Beadle and Tatum also showed that each mutant was defective in a single gene.

Accordingly, they formulated the one gene-one enzyme hypothesis, which states

that the function of an individual gene is to dictate the production of a

specific enzyme.

The one gene-one enzyme hypothesis has

been amply confirmed, but with some important modifications. First it was

extended beyond enzymes to include all types of proteins. For example,

alpha-keratin, the structural protein of your hair, is the product of a gene.

So biologists soon began to think in terms of one gene-one protein. Then it was

discovered that many proteins have two or more different polypeptide chains,

and each polypeptide is specified by

its own gene. Thus, Beadle and Tatum's hypothesis has come to be restated as

one gene-one polypeptide.

From

Nucleotide Sequence to Amino Acid Sequence: An Overview

Stating that genetic information in DNA is

transcribed into RNA and then translated into polypeptides does not explain how

these processes occur. Transcription and translation are linguistic terms, and

it is useful to think of nucleic acids and polypeptides as having languages,

too. To understand how genetic information passes from genotype to phenotype, we

need to see how the chemical language of DNA is translated into the different

chemical language of polypeptides.

What exactly is the language of nucleic

acids? Both DNA and RNA are polymers made of monomers in specific sequences

that carry information, much as specific sequences of letters carry information

in English. In DNA, the monomers are the four types of nucleotides, which

differ in their nitrogenous bases (A, T, C, and G). The same is true for RNA,

although it has the base U instead of T.

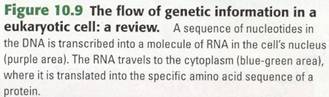

DNAs language is written as a linear

sequence of nucleotide bases, a sequence such as the one you see on the

enlarged DNA strand in Figure 10.10.

Specific sequences of bases, each with a beginning and an end, make up

the genes on a DNA strand. A typical gene consists of thousands of nucleotides,

and a DNA molecule may contain thousands of genes.

When DNA is transcribed, the result is an

RNA molecule. The process is called transcription because the nucleic acid

language of DNA has simply been rewritten (transcribed) as a sequence of bases

of RNA; the language is still that of nucleic acids. The nucleotide bases of

the RNA molecule are complementary to those on the DNA strand. As you will soon

see, this is because the RNA was synthesized using the DNA as a template.

Translation is the conversion of the

nucleic acid language into the polypeptide language. Like nucleic acids,

polypeptides are polymers, but the monomers that make them up -- the letters

of the polypeptide alphabet are the 20 amino acids common to all organisms.

Again, the language is written in a linear sequence, and the sequence of

nucleotides of the RNA molecule dictates the sequence of amino acids of the

polypeptide. But remember, RNA is only a messenger; the genetic information

that dictates the amino acid sequence is based in DNA.

What are the rules for translating the RNA

message into a polypeptide? In other words, what is the correspondence between

the nucleotides of an RNA molecule and the amino acids of a polypeptide? Keep

in mind that there are only four different kinds of nucleotides in DNA (A, G,

C, T) and RNA (A, G, C, U). In translation, these four must somehow specify 20

amino acids. If each nucleotide base coded for one amino acid, only 4 of the 20

amino acids could be accounted for. What if the language consisted of

two-letter code words? If we read the bases of a gene two at a time, AG, for

example, could specify one amino acid, while AT could designate a different

amino acid. However, when the four bases are taken two by two, there are only

16 (that is, 41 possible arrangements-still not enough to specify all 20 amino

acids.

Triplets of bases are

the smallest "words" of uniform length that can specify all the amino

acids. There can be 64 ( that is, 43) possible code words of this

type-more than enough to specify the 20 amino acids. Indeed, there are enough

triplets to allow more than one coding for each amino acid. For example, the

base triplets AAT and AAC could both code for the same amino acid - and, in

fact, they do.

Experiments have verified that the flow of

information from gene to protein is based on a triplet code. The genetic

instructions for the amino acid sequence of a polypeptide chain are written in

DNA and RNA as a series of three-base words called codons. Three-base

codons in the DNA are transcribed into complementary three-base codons in the

RNA, and then the RNA codons are translated into amino acids that form a

polypeptide. Next we turn to the codons themselves.

The

Genetic Code

In 1799, a large stone tablet was found in

Rosetta, Egypt, carrying the same lengthy inscription in three ancient scripts:

Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and Egyptian written in a simplified script. The

Rosetta stone provided the key that enabled scholars to crack the previously

indecipherable hieroglyphic code.

In cracking the genetic code, the set of

rules relating nucleotide sequence to amino acid sequence, scientists wrote

their own Rosetta stone. It was based on a series of elegant experiments , that

revealed the amino acid translations of each of the nucleotide - triplet code

words. The first codon was deciphered in 1961 by American biochemist Marshall

Nirenberg. He synthesized an artificial RNA molecule by linking together

identical RNA nucleotides having uracil as their base. No matter where this

message started or stopped, it could contain only one type of triplet codon:

uuu. Nirenberg added this "poly U" to a test tube mixture containing

ribosomes and the other ingredients required for polypeptide synthesis. This

mixture translated the poly U into a polypeptide containing a single kind of

amino acid, phenylalanine. In this way, Nirenberg learned that the RNA codon

UUU specifies the amino acid phenylalanine (Phe). By variations on this method,

the amino acids specified by all the codons were determined.

Figure 10.11 The dictionary of the genetic code, listed by RNA

codons. The three bases of an RNA codon are designated here as the first,

second, and third bases. Practice using this dictionary by finding the codon

UGG. This is the only codon for the amino acid tryptophan (Trp), but most amino

acids are specified by two or more codons. For example, both UUU and UUG stand

for the amino acid phenylalanine (Phe). Notice that the codon AUG not only

stands for the amino acid methionine (Met) but also functions as a signal to

"start" translating the RNA at that place. Three of the 64 codons

function as "stop" signals. Anyone of these termination codons marks

the end of a genetic message.

As Figure 10.11 shows, 61 of the 64

triplets code for amino acids. The triplet AUG has a dual function: It not only

codes for the amino acid methionine (Met) but can also provide a signal for the

start of a polypeptide chain. Three of the other codons do not designate amino

acids. They are the stop codons that instruct the ribosomes to end the

polypeptide.

In Figure 10.11 that there is redundancy

in the code but no ambiguity. For example, although codons UUU and UUC both

specify phenylananine (redundancy), neither of them ever represent any other

amino acid (no redundancy). The codons

in the figure are the triplets found in RNA. They have a straightforward,

complementary relationship to the codons in DNA. The nucleotides making up the

codons occur in a linear order along the DNA and RNA, with no gaps or

"punctuation" separating the codons.

Almost all of the genetic code is

shared by all organisms, from the simplest bacteria to the most complex

plants and animals. The universality of the genetic vocabulary suggests that it

arose very early in evolution and was passed on over the eons to all the

organisms living on Earth today. Such universality is extremely important to

modern DNA technologies. Because the code is the same in different species,

genes can be transcribed and translated after transfer from one species to

another, even when the organisms are as different as a bacterium and a human,

or a firefly and a tobacco plant (Figure 10.11.). This allows scientists to mix

and match genes from various species-a procedure with many useful applications.

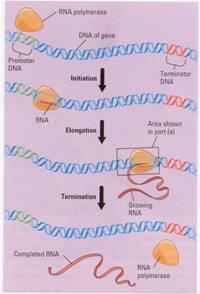

Transcription:

From DNA to RNA

Let's look more closely at transcription,

the transfer of genetic information from DNA to RNA. An RNA molecule is

transcribed from a DNA template by a process that resembles the synthesis of a

DNA strand during DNA replication. Figure 10.13a is a close-up view of this

process. As with replication, the two DNA strands must first separate at the

place where the process will start. In transcription, however, only one of the

DNA strands serves as a template for the newly forming molecule. The

nucleotides that make up the new RNA molecule take their places one at a time

along the DNA template strand by forming hydrogen bonds with the nucleotide

bases there. Notice that the RNA nucleotides follow the same base-pairing rules

that govern DNA replication, except that U, rather than T, pairs with A. The

RNA nucleotides are linked by the transcription enzyme RNA polymerase.

Figure 10.13b is an overview of the

transcription of an entire gene. Special sequences of DNA nucleotides tell the

RNA polymerase where to start and where to stop the transcribing process.

Initiation of

Transcription The "start transcribing" signal

is a nucleotide sequence called a promoter, which is located in the DNA at the

beginning of the gene. A promoter is a specific place where RNA polymerase

attaches. The first phase of transcription, called initiation, is the

attachment of RNA polymerase to the promoter and the start of RNA synthesis.

For any gene, the promoter dictates which of the two DNA strands is to be

transcribed (the particular strand varying from gene to gene).

RNA Elongation

During the second phase of transcription, elongation, the RNA grows longer. As

RNA synthesis continues, the RNA strand peels away from its DNA template,

allowing the two separated DNA strands to come back together in the region

already transcribed.

Termination of

Transcription In the third phase, termination, the RNA

polymerase reaches a special sequence of bases in the DNA template called a

terminator. This sequence signals the end of the gene. At this point, the

polymerase molecule detaches from the RNA molecule and the gene.

In addition to producing RNA that encodes

amino acid sequences, transcription makes two other kinds of RNA that are

involved in building polypeptides. We discuss these kinds of RNA a little

later.

The

Processing of Eukaryotic RNA

In prokaryotic cells, which lack nuclei,

the RNA transcribed from a gene immediately functions as the messenger molecule

that is translated, called messenger RNA (mRNA). But this is not the case in

eukaryotic cells. The eukaryotic cell not only localizes transcription in the

nucleus but also modifies, or processes, the RNA transcripts there before

they move to the cytoplasm for translation by the ribosomes.

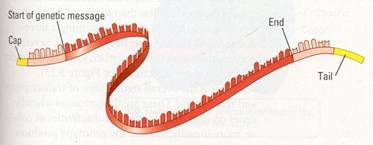

One kind of RNA processing is the addition

of extra nucleotides to the ends of the RNA transcript. These additions, called

the cap and tail, protect the RNA from attack by cellular enzymes and help

ribosomes recognize the RNA as mRNA.

(a)

A close-up view of transcription (b)

Transcription of a gene

Figure 10.13 Transcription. (a) As ANA nucleotides base-pair one

by one with DNA bases on one DNA strand (called the template strand), the

enzyme ANA polymerase links the ANA nucleotides into an ANA chain. The orange

shape in the background is the ANA polymerase. (b) The transcription of an

entire gene occurs in r three phases: initiation, elongation, and termination

of the ANA. The section of DNA t where the ANA polymerase starts is called the

promoter; the place where it stops is , called the terminator.

Figure

10-14 Figure 10-15

Figure 10.14 The production of messenger RNA in a eukaryotic

cell. Both exons and introns are transcribed from the DNA. Additional

nucleotides, making up the cap and tail, are attached It the ends of the RNA

transcript. The exons are spliced together. The Iroduct, a molecule of

messenger RNA (mRNA), then travels to the :ytoplasm of the cell. There the

coding sequence will be translated.

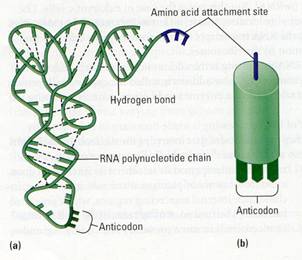

Figure 10.15 The structure of tRNA. (a) The RNA

polynucleotide is a "rope" whose appendages are the nitrogenous

bases. Dashed lines are hydrogen bonds, which connect some of the bases. The

site where an amino acid will attach is a three nucleotide segment at one end

(purple). Note the three-base anti codon at the bottom of the molecule (dark

green). The overall shape of a tRNA molecule is like the letter L. (b) This is

the representation of tRNA that we use in later diagrams.

Another type of RNA processing is made

necessary in eukaryotes by noncoding stretches of nucleotides that interrupt --

nucleotides that actually code for amino acids. It is as if unintelligible

sequences of letters were randomly interspersed in an otherwise intelligible

document. most genes of plants animals, It turns out, include such internal

noncoding regions, which are called introns. (The functions of introns,

if any, and how introns evolved remain a mystery.) The coding regions -- the

parts of a gene that are expressed - are called exons. As Figure 10.14

illustrates, both exons and introns are transcribed from DNA into RNA. However,

before the RNA leaves the nucleus, the introns are removed, and the exons are

joined to produce an mRNA molecule with a continuous coding sequence. This

process is called RNA splicing. RNA splicing is believed to playa significant

role in humans in allowing our approximately 35,000 genes to produce many

thousands more polypeptides. This is accomplished by varying the exons that are

included in the final mRNA. With capping, tailing, and splicing completed, the

"final draft" of eukaryotic mRNA is ready for translation.

Translation:

The Players

As we have already discussed, translation

is a conversion between different languages-from the nucleic acid language to

the protein language-and it involves more elaborate machinery than

transcription.

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

The first important ingredient required for translation is the mRNA produced by

transcription. Once it is present, the machinery I used to translate mRNA

requires enzymes and sources of chemical energy, such as ATP. In addition,

translation requires two heavy-duty components: ribosomes and a kind of RNA

called transfer RNA.

Transfer RNA (tRNA)

Translation of any language into another language requires an interpreter, person or device that can recognize the

words of one language and convert them into the other. Translation of the

genetic message carried in mRNA into the amino acid language of proteins also

requires an interpreter. To convert the three-letter words ( codons ) of

nucleic acids to the one-letter, amino acid words of proteins, a cell uses a

molecular interpreter, a type of RNA called transfer RNA. abbreviated tRNA

(Figure 10.15).

Figure

10-16 Figure

10-17

Figure 10.16 The ribosome. (a) A simplified diagram of a

ribosome, showing its two subunits and sites where mRNA and tRNA molecules

bind. (b) When functioning in polypeptide synthesis, a ribosome holds one

molecule of mRNA and two molecules of tRNA. The growing polypeptide is attached

to one of the tRNAs.

Figure 10.17 A molecule of mRNA. The pink ends are

nucleotides that are not part of the message; that is, they are not translated.

These nucleotides, along with the cap and tail (yellow),

help the mRNA attach to the ribosome.

A cell that is ready to have some of its

genetic information translated into polypeptides has in its cytoplasm a supply

of amino acids, either obtained from food or made from other chemicals. The

amino acids themselves cannot recognize the codons arranged in sequence along

messenger RNA. It is up to the cell's molecular interpreters, tRNA molecules,

to match amino acids to the appropriate codons to form the new polypeptide. To

perform this task, tRNA molecules must carry out two distinct functions: ( 1)

to pick up the appropriate amino acids, and (2) to recognize the appropriate

codons in the mRNA. The unique structure of tRNA molecules enables them to

perform both tasks-

As shown in Figure 10.15a, a tRNA molecule

is made of a single strand of RNA - one polynucleotide chain-consisting of

about 80 nucleotides. The chain twists and folds upon itself, forming several

double-stranded regions in which short stretches of RNA base-pair with other

stretches. At one end of the folded molecule is a special triplet of bases

called an anticodon. The anticodon triplet is complementary to a codon triplet

on mRNA. During translation, the anticodon on tRNA recognizes a particular

codon on mRNA by using base-pairing rules. At the other end of the tRNA

molecule is a site where an amino acid can attach. Although all tRNA molecules

are similar, there is a slightly different version of tRNA for each amino acid.

Ribosomes Ribosomes are the organelles that coordinate

the functioning of the mRNA and tRNA and actually make polypeptides. As you can

see in Figure 10.16a, a ribosome consists of two subunits. Each subunit is made

up of proteins and a considerable amount of yet another kind of RNA, ribosomal

RNA (rRNA). A fully assembled ribosome has a binding site for mRNA on its small

subunit and binding sites for tRNA on its large subunit. Figure 10.16b shows

how two tRNA molecules get together with an mRNA molecule on a ribosome. One of

the tRNA binding sites, the P site, holds the tRNA carrying the growing

polypeptide chain, while another, the A site, holds a tRNA carrying the next

amino acid to be added to the chain. The anticodon on each tRNA base pairs with

a codon on mRNA. The subunits of the ribosome act like a vise, holding the tRNA

and mRNA molecules close together. The ribosome can then connect the amino acid

from the A site tRNA to the growing polypeptide.

‘

‘

Figure

10.18 Figure 10.19

Figure 10.18 The initiation of translation. (1) An mRNA molecule

binds to a small ribosomal subunit. A special initiator tRNA then binds to the

start codon, where translation is to begin on the mRNA. The initiator tRNA

carries the amino acid methionine (Met); its anticodon, UAC, binds to the start

codon, AUG. (2) A large ribosomal

subunit binds to the small one, creating a functional ribosome. The initiator

tRNA fits into the P site on the ribosome.

Figure

10.20

Translation:

The Process

Translation can be divided into the same

three phases as: transcription initiation, elongation, and termination.

Initiation

This first phase brings together the mRNA, the first amino acid with its

attached tRNA, and the two subunits of a ribosome. An mRNA molecule, even after

splicing, is longer than the genetic message it carries (Figure 10.17)

.Nucleotide sequences at either end of the molecule are not part of the

message, but along with the cap and tail in eukaryotes, they help the mRNA bind

to the ribosome. The initiation process determines exactly where translation will begin so that the mRNA codons will

be translated into the correct sequence of amino acids. Initiation occurs in

two steps, as shown in Figure 10.18.

Elongation

Once initiation is complete, amino acids are added one by one to the first ammo

acid. Each addition occurs ill a three-step elongation process (Figure 10.19).

Step (1) Codon

recognition. The anticodon of an

incoming tRNA molecule, carrying its ammo acid, pairs with the mRNA codon in

the A site of the ribosome.

Step (2) Peptide bond formation. The polypeptide leaves the

tRNA in the P site and attaches to the amino acid on the tRNA in the A site.

The ribosome catalyzes bond formation. Now the chain has one more amino acid.

Step (3) Translocation. The P site tRNA now leaves the

ribosome, and the ribosome translocates (moves) the remaining tRNA, carrying

the growing polypeptide, to the P site. The mRNA and tRNA move as a unit. This

movement brings into the A site the next mRNA codon to be translated, and the

process can start again with step (1).

Termination

Elongation continues until a stop codon reaches the ribosome's A site. Stop.

codons-UAA, UAG, and UGA-do not code for amino acids but instead tell

translation to stop. The completed polypeptide, typically several hundred ammo

acids long, is freed, and the ribosome splits into its subunits.

Review:

DNA > RNA > Protein

Figure 10.20 reviews the flow of genetic

information in the cell, from DNA to RNA to protein. In eukaryotic cells,

transcription-the stage from DNA to RNA-occurs in the nucleus, and the RNA 8

Peptide bond formation is processed before it enters the cytoplasm. Translation

is rapid; a single ribosome can make an average-size polypeptide in less an a

minute. As it is made a polypeptide coils and folds, assuming a three-dimensional

shape, its tertiary structure. Several polypeptides may come together, forming

a protein with quaternary structure.

What is the overall significance of

transcription and transcription? These are the processes whereby genes control

the structures and activities of cells location or, more broadly, the way the

genotype produces the phenotype. The

chain command originates with information in the gene, a specific linear

sequence of nucleotides in the DNA. The

gene serves as a template, dictating the transcription of a complementary

sequence of nucleotides in mRNA. In turn, mRNA specifies the linear sequence in

which amino acids appear in a polypeptide. Finally, the proteins that form from

the polypeptides determine the appearance and capabilities of the cell and

organism.

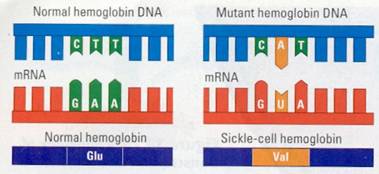

Mutations

Since discovering how genes are translated

into proteins, scientists have been able to describe many heritable differences

in molecular terms. For instance, when a child is born with sickle-cell

disease, the condition can be traced back through a difference in a protein to

one tiny change in a gene. In one of the polypeptides in the hemoglobin

protein, the sickle-cell child has a single different amino acid. This

difference is caused by a single nucleotide difference in the coding strand of

DNA (Figure 10.21 ). In the double helix, a base pair is changed.

The sickle-cell allele is not a unique

case. We now know that the various alleles of many genes result from changes in

single base pairs in DNA. Any change in the nucleotide sequence of DNA is

called a mutation. Mutations can involve large regions of a chromosome or just

a single nucleotide pair, as in the sickle-cell allele.

Types of Mutations

Mutations within a gene can be divided into two general categories: base

substitutions and base insertions or deletions (Figure 10.22 ) .A base

substitution is the replacement of one base, or nucleotide, by another.

Depending on how a base substitution is translated, it can result in no change

in the protein, in an insignificant change, or in a change that might be

crucial to the life of the organism. Because of the redundancy of the genetic

code, some substitution mutations have no effect. For example, if a mutation

causes an mRNA codon to change from GAA to GAG, no change in the protein product

would result, because GAA and GAG both code for the same amino acid (Glu). Such

a change is called a silent mutation.

Other changes of a single nucleotide do

change the amino acid coding, Such mutations are called missense mutations. For

example, if a mutation causes an mRNA codon to change from GGC to AGC, the

resulting protein will have a serine (Ser) instead of a glycine (Gly) at this

position (see Figure 10.22a). Some missense mutations have little or no effect

on the resulting protein, but others, as we saw in the sickle-cell case, cause

changes in the protein that prevent it from performing normally.

Occasionally, a base substitution leads to

an improved protein or one with new capabilities that enhance the success of

the mutant organism and its descendants. Much more often, though, mutations are

harmful. Some base substitutions, called nonsense mutations, change an amino

acid codon into a stop codon. For example, if an AGA (Arg) codon is mutated to

a UGA ( stop) codon, the result will be a prematurely terminated protein, which

may not function properly.

Figure 10.21 The molecular basis of sickle-cell disease. The

sickle-cell allele differs from its normal counter-part, a gene for hemoglobin,

by only one nucleotide, This difference changes the mRNA codon from one that

codes for the amino acid glutamic acid (Glu) to one that codes for valine

(Val).

Figure 10.22 Two types of mutations and their effects. Mutations

are changes in DNA, but they are represented here as reflected in mRNA and its

polypeptide product, (a)1n the base substitution shown here, an A replaces a G

in the fourth codon of the mRNA, The result in the polypeptide is a serine

(Ser) instead of a glycine (Gly), This amino acid substitution mayor may not

affect the protein's function, (b) When a nucleotide is deleted (or inserted),

the reading frame is altered, so that all the codons from that point on are

misread, The resulting polypeptide is likely to be completely nonfunctional,

Mutations involving the insertion or

deletion of one or more nucleotides in a gene often have disastrous effects.

Because mRNA is read as a series of nucleotide triplets during translation,

adding or subtracting nucleotides may alter the reading frame (triplet

grouping) of the genetic message. All the nucleotides that are

"downstream" of the insertion or deletion will be regrouped into

different codons. For example, consider an mRNA molecule containing the

sequence AAG-UUU-GGC-GCA; this codes for Lys-Phe-Gly-Ala. If a U is deleted in

the second codon, the resulting sequence will be AAG- UUG-GCG-CAU, which codes

for Lys-Leu-Ala-His (see Figure 10.22b). The altered polypeptide is likely to

be nonfunctional. Inserting one or two mRNA nucleotides would have a similarly

large effect.

Mutagens What

causes mutations? Mutagenesis, the creation of mutations, can occur in a number

of ways. Mutations resulting from errors during DNA replication or

recombination are known as spontaneous mutations, as are other mutations of

unknown cause. Other sources of mutation are physical and chemical agents

called mutagens. The most common physical mutagen is high-energy radiation,

such as X-rays and ultraviolet (UV) light. Chemical mutagens are of various

types. One type, for example, consists of chemicals that are similar to normal

DNA bases but that base-pair incorrectly when incorporated into DNA. Many

mutagens can act as carcinogens, agents that cause cancer. What can you do to

avoid exposure to mutagens? Several lifestyle practices can help, including

wearing protective clothing and sun screen to minimize direct exposure to the

sun’s rays and not smoking. But such precautions are not fool proof; for

example, you cannot entirely avoid UV radiation.

Although mutations are often harmful, they

are also extremely useful, both in nature and in the laboratory. Mutations are

the source of the rich diversity of genes in the living world, a diversity that

makes evolution by natural selection possible (Figure 10.23). Mutations are

also essential tools for geneticists. Whether naturally occurring or created in

the laboratory, mutations are responsible for the different alleles needed for

genetic research.