WEHqN

Air University Press; Maxwell Air

Force Base, Alabama November 1995

This

Book is Dedicated to Charlie

Author Ed Whitcomb and

Charles “Charlie” Lunn

Charlie,

a Pan American Navigator

was

asked by Army Air Corps Gen Emmons

to

set up a school to teach Celestial Navigation

University

of Miami set up classrooms

and

Charlie began teaching, the Class of 40-A being the first.

Ed

Whitcomb, one of 47 in the class,

tells

of what happened to classmates,

who

were to play such a crucial roll in coming events.

WW

II broke out and these few were destined to

guide

the way by reading the stars,

thanks

to Charlie Lunn showing them how.

Contents

|

Chapter |

Name |

Page |

|

ix |

FORWARD |

2 |

|

xi |

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR |

3 |

|

xiii |

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS |

3 |

|

xv |

INTRODUCTION |

3 |

|

1 |

Navigators

of the First Global Air Force |

4 |

|

2 |

Prelude to

War |

12 |

|

3 |

Death on a

Bright Sunday Morning |

16 |

|

4 |

Attack on

Clark Field |

18 |

|

5 |

George

Berkowitz |

21 |

|

6 |

Harry

Schreiber |

23 |

|

7 |

William

Meenagh |

26 |

|

8 |

Reqroup |

29 |

|

9 |

Richard

Wellington Cease |

30 |

|

10 |

Paul E.

Dawson |

33 |

|

11 |

George

Markovich |

34 |

|

12 |

War Plan

Orange III |

39 |

|

13 |

Carl R.

Wildner |

42 |

|

14 |

Harry

McCool |

46 |

|

15 |

Merrill

Kern Gordon Jr |

49 |

|

16 |

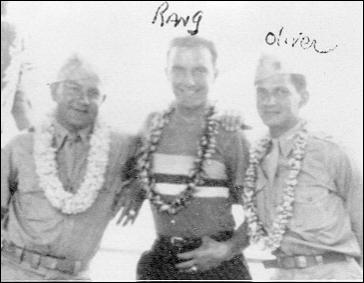

Francis B.

Rang |

52 |

|

17 |

Corregidor |

54 |

|

18 |

William

Scott Warner |

57 |

|

19 |

Jay M.

Horowitz |

60 |

|

20 |

The

Superfortress |

66 |

|

21 |

Boselli and

the Sacred Cow |

71 |

|

22 |

New Hope |

76 |

|

23 |

Bataan to

Santo Tomas |

79 |

|

24 |

Deliverance |

83 |

|

25 |

A Visit

with Charlie |

87 |

|

|

Appendix |

|

|

A |

History |

90 |

|

B |

Class of

40-A |

92 |

|

|

Bibliography |

93 |

|

|

|

|

chapter ix

Foreword

In November 1940, 44 young military

cadets graduated from the first Army Air Corps Navigational Class at Miami

University in Coral Gables, Florida.

The cadets came from all parts of the United States-from the urban areas

of the East Coast, westward to the Appalachian Mountains, to the Midwest and prairie

states, to the Rocky Mountains, and the West Coast. These young men came from the inner cities, the farmlands, the

mountains, and coastal regions, and they were all volunteers. Most were college educated and in the prime

of life. World War II was raging in

Europe and it was becoming increasingly difficult for the United States to

remain neutral. A few farsighted men in

our small Army Air Corps saw the essential requirement for trained celestial

navigators in our military aircraft.

The

instructor for this navigational class was a 34-year-old high school dropout by

the name of Charles J. Lunn. Charlie

Lunn had first learned the art of celestial navigation aboard freighter ships

in the Caribbean and later as the navigator aboard Pan American Airline planes

flying to Europe and Asia.

This

book was written by one of those young navigators, Edgar D. Whitcomb, from

Hayden, Indiana. Ed Whitcomb tells

about these young comrades-in-arms and draws vivid word portraits of them as we

learn of their assignments to Air Corps units.

We learn how they survived and how some died in World War II. We learn about Ed's own pre-Pearl Harbor

assignment with the 19th Bombardment Group at Clark Field in the Philippines

and the unfortunate, and perhaps inexcusable, decision not to deploy our B-17

Flying Fortress bombers immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor resulting

in the loss of 40 percent of those aircraft as they sat parked at Clark Field

when the Japanese destroyed that vital military air base on the afternoon of 8

December 1941.

Charles J. Mott

Charles J. Mott Colonel, USAR, Retired

chapter xi

About

the Author

Edgar ("Ed") D. Whitcomb

enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1940 and was commissioned a second lieutenant

the following year with the rating of aerial navigator. He served two combat tours in the

Philippines during WWII. After his

active military service, he graduated from the Indiana University School of

Law. He practiced law in southern

Indiana over a period of 30 years including two years as an assistant United

States Attorney. A graduate of the Army

Command and General Staff Course and the Air Force Staff Course he served in

the Air Force Reserve for 31 years and retired with the rank of colonel. Whitcomb served the State of Indiana as a

senator, secretary of state, and governor.

Whitcomb's

experiences of evading capture, then later being taken prisoner by the

Japanese, escaping by an all-night swim from Corregidor, his recapture, and his

ultimate repatriation from China as a civilian under an assumed name.

Upon

retirement from the practice of law at the age of 68, Whitcomb took to sailing

the open seas. He purchased a 30-foot

sailboat in Greece and sailed solo across both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. When not sailing Whitcomb makes his home in

the village of Hayden in rural southern Indiana.

Chapter xiii

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the following

people who contributed so generously to make this book possible: Gen Eugene L.

Eubank, Elaine Bath, Ned Vifquain, Phillip Cease, Charles and Sylvia Lunn, Gen

Austin J. Montgomery, Joe H. Sherlin, Dr Ron Johnson, Mary 0. Cavett, Ruth

King, Carl and Shelley Mydans, Frank Kurtz, Elmer Smith, Laura Showalter,

Raymond Teborek, William Scott Warner, Carl R. Wildner, George Markovich,

Harold C. McAuliff, John W. Cox, Jr., Harry McCool, Robert A. Trenkle, Theodore

J. Boselli, Paul Dawson, Merrill and Bette Gordon, Harry Schreiber, Gen A. P.

Clark, Harold Fulghum, W. R. Stewart, Jr., Edward M. Jacquet, Dr James

Titus. Emily Adams. and the staff at

the AU Press.

Chapter xv

Introduction

In August 1940 a group of young men

from all parts of the United States converged upon Coral Gables, Florida, to

become cadets in a military navigation training program. Raised as children of the Great Depression of

the 1920s and 1930s, what they wanted more than anything else in life was to

fly airplanes. They had all volunteered

for the US Army Air Corps with hopes for becoming pilots, but the Air Corps had

other ideas. They would become

navigators on the world's finest bomber, the B- 17 Flying For-tress.

The

cadets did not think of themselves as warriors. None of them had ever seen a Flying Fortress. They were civilians who wanted to fly and

joining the Air Corps was a means to that end.

The thought of flying where man had never flown before or of bombing

cities all around the world was farthest from their minds as they struggled

with the intricacies of celestial navigation.

On

Celestial Wings tells of the

development of the first program to mass produce celestial navigators as

America geared up for entry into WWII.

It also tells of heartrending tragedies resulting from America's lack of

preparedness for war and the fight against overwhelming odds in experiences of

members of the US Army Air Corps Navigation School class of 40-A. It tells of their honors and victories and

their disappointments and bitter defeats in a war unlike any that will ever

occur again.

Chapter

1

Navigators

of the First Global Air Force

Army Air Corps Navigation Class 40-A

The University of Miami band blared

its music through the majestic Biltmore Hotel as 44 khaki-clad cadets marched

onto the stage of the big ballroom. It

was a historic occasion because we were the first graduating class of professional

aerial navigators for the United States' military services. We were to become known as the Class of

40-A. On stage with the 44 of us were

representatives of the University of Miami at Coral Gables, Florida, the United

States Army Air Corps, and Pan American Airways-the organizations that had put

together America's first navigation training program. It was among the first programs of World War II in which

business, military, and university personnel combined efforts in the interest

of national defense.

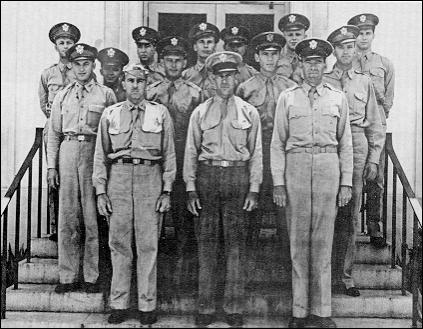

Cadets in formation in front of their

quarters, the San Sebastian Hotel

The date was 12 November 1940. World War II had been raging in Europe for

more than a year, and Adolph Hitler had sent his troops into Poland, Norway,

Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

Fighting, death, and destruction were far away from US shores. America was enjoying peace with a president

named Franklin Delano Roosevelt who had vowed that he would never send an

American boy to die on foreign soil.

Congress had passed laws enacting the draft, but the men on the platform

in Coral Gables were not concerned about that.

They were all volunteers who anticipated one thing: to fly!

We came in early August 1940 to what

became the fountainhead of navigational knowledge. {1} Few people traveled by

commercial airlines in those days. We

came by bus, boat, train, and automobile from the crowded streets of New York

City, the lonely rangelands of Montana, and the peaceful small towns of the

Midwest. Many of my classmates were

first and second generation Americans of Serbian, Jewish, Italian, Polish, and

English extraction. It was an

all-American group including, among others, the family names of Markovich,

Berkowitz, Boselli, Vifquain, and Meenagh.

The class members were young men in

their early twenties, bright-eyed and eager to succeed in navigation school so

they could fly. We had only a vague

idea of the complexities of celestial navigation. None of us had ever known an aerial navigator nor could have had

any idea of the perils the future held for us.

We could not have envisioned that we would be flying courses where no

man had ever flown, dropping bombs on civilian cities around the world and

seeing our classmates shot out of the sky.

My roommate, Theodore J. Boselli, a

former champion bantamweight boxer from Clemson University, would later

navigate the first presidential plane.

Walter E. Seamon, son of the mayor of West Jefferson, Ohio, would also

be assigned to the president's plane.

George Markovich, a brilliant graduate of the University of California

at Berkeley, would guide a plane called the Bataan for the great Gen Douglas

MacArthur in his flights around the Southwest Pacific. Russell M. Vifquain, the blonde-headed son

of an Iowa college professor, had led Iowa State University to be runner-up in

the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) golf competition. In the years ahead he would be with Gen

Curtis LeMay dropping tons of incendiary bombs into the crowded heart of Tokyo,

Japan. Jay Horowitz, a happy Jewish boy

from Sweetwater, Tennessee, would suffer more agony as a prisoner at the hands

of the Japanese than anyone could have imagined. These and many others were my classmates as we entered into the

academic phase of celestial navigation.

Aerial view of the Pan American

Airport Miami

Pan American Airways Hangers

But it was 1940, and we were in the

city of Coral Gables. The US was at

peace and our thoughts were not of war.

Our home during the 12-week course of training was the stately San

Sebastian Hotel at the comer of Le Jeune and University streets. In our first military formations we wore

T-shirts, civilian clothes, and a variety of uniforms from previous military

organizations. We were a second "Coxey's

Army" ready to be molded into military men and more importantly, celestial

navigators. [1] One element of cadet life was missing. There were no upper classes, no lower class,

and thus no hazing.

One of the first formations

Capt Norris B. Harbold, a 1928

product of the United States Military Academy at West Point, was in charge of

the detachment. He had a history of

efforts to promote celestial navigation training in the Air Corps. We conducted close-order drill formations on

the streets near the hotel where there was scant vehicular traffic. Coral Gables on the outskirts of Miami was a sleepy and almost desolate city

after the big land development boom and later depression of the 1930s. There were dozens of city blocks where

streets, sidewalks, curbs, and fire hydrants supported vacant lots overgrown

with weeds.

The

cadets marched in ragged military formations across the street to the

"Cardboard College"-a group of buildings intended to serve the

University of Miami until a new campus was established. The university's grandiose plans for new

buildings had stopped dead with the advent of the big depression. But the temporary facilities were adequate

for our 240 hours of ground training in navigation and meteorology.

The

development of the navigation training program had come about in a very unusual

way. Gen Delos Emmons, chief of General

Headquarters of the US Army Air Corps, had been aboard a giant Pan American

clipper on a fact-finding mission to Europe in 1939. All night the big silver clipper lumbered along on its flight

from New York to the island of Horta in the Azores. While other passengers dozed, General Emmons observed the plane's

navigator industriously plotting his course by celestial navigation. The general stood on the flight deck in awe

of the proficiency of the work. Then as

the stars faded away in the light of a new day, the navigator pointed to a dark

mound on the distant horizon dead ahead of the aircraft.

"That

is the island of Horta," announced Charles J. Lunn, the navigator.

"Amazing!"

exclaimed the general.

"It

would be more amazing if it were not there," replied Lunn matter of

factly. {2}

General

Emmons had more than a passing interest in this feat of expertise in celestial

navigation. )Ws victories in Europe suggested alarming possibilities for US

involvement in the European war. The

Air Corps urgently needed a lot of well-trained and highly skilled celestial

navigators. General Emmons knew that

there was no program in the Air Corps to do the job although the Air Corps had

tried on several occasions to establish celestial navigation schools. At that time, most military flights were

conducted within the continental limits of the United States. Therefore, there was little stimulus for

flying officers to do more than make a hobby of celestial navigation. A few officers including Norris B. Harbold,

Eugene L. Eubank, Albert F. Hegenberger, Glenn C. Jamison, Lawrence J. Carr,

and Curtis E. LeMay had taken particular interest in celestial navigation, but

by the spring of 1940, the Army Air Corps had only 80 experienced celestial

navigators. It would need thousands to

man the new bombers on order for the Air Corps. {3}

"How

many people could you teach to do this?" Emmons asked Lunn.

"Just

as many as could hear my voice," was Lunn's succinct reply.

The

conversation planted an idea in the general's mind. With whatever else he may have learned on his fact-finding

mission to Europe, he came back to Washington, D.C., with an idea for training

navigators.

Upon

his return he contacted Juan Tripp, president of Pan American Airways and Dr B.

F. Ashe, president of the University of Miami.

Their meetings culminated in an agreement whereby Pan American would

provide navigational training with Charles J. Lunn as the chief navigation

instructor. The University of Miami

would provide food, housing, and classrooms for instruction at the rate of

$12.50 per cadet per week. The cadets

were in place, and the program was under way even before the agreement was

signed. {4}

Charlie

Lunn seemed the most unlikely person to be teaching a university class. His academic credentials were woefully

deficient. He had no college degrees

whatsoever. He had never attended a

college or university. The fact was

Charles J. Lunn, chief navigation instructor at the University of Miami in

Coral Gables, Florida, in 1940, had failed his sophomore year at Key West High

School. He was a high school dropout.

Charlie and

his sister had stood at the head of their classes in grammar school and in high

school until Charlie's interests turned to girls and basketball. At 16 years of age, he was a good enough

athlete to draw $10 a game playing for the Key West Athletic Club team. However, as a result of his extracurricular

activities, his academic standing declined to the point that he decided to

leave school.

Nineteen

years later, he found himself standing before a class of college-trained and

educated students from all parts of the United States. Many of them had college degrees in

engineering, education, and a variety of other fields. It was Charlie's job to train them in the

complicated art of celestial navigation.

When Charlie left high school, his

father made it clear to him that he was to get himself reinstated in high

school or get a job to support himself Since he had grown weary of dull

classroom life, Charlie set out to find a job.

In

1921 there were few employment opportunities in Key West for a 16-year-old high

school dropout. Sponging (gathering

sponges from the sea) and fishing were about the only jobs available on the

island and such jobs were not attractive to young Lunn. The 7th US Navy Base, where many naval

vessels stopped for fuel and water, was one of the chief employers in Key

West. Charlie was unable to find a job

there because 18 was the minimum age for employment with the government.

Like other boys his age, he was

fascinated by the foreign ships that came into Key West Harbor. He had talked to sailors about their voyages

to far away ports and learned that it would be possible to get a job as an

oiler on an oceangoing ship.

So

at the age of 16, Charlie took his first job oiling the engine on a freighter

of the P & 0 Steamship Company plying between Key West, Tampa, and

Havana. It did not take the lad very

long to grow tired of his work in the steaming hot and smelly bowels of the ship. If there were any romance and adventure in

that life, they completely escaped him.

After a couple of trips, he applied for a job working on the top deck

where he would have more opportunity to learn about sailing.

As

a deck hand, Charlie was industrious and inquisitive. He asked questions and he studied books until, at the age of 18,

he became third mate on his ship.

From

childhood, Charlie had heard stories of shipwrecks all along the Florida

Keys. Spanish sea captains with

millions of dollars in treasure had lost their ships in those waters as they

made their way back toward Spain. He

also knew the nineteenth century tales of how some Key West natives had ridden

mules in the shallow waters along the reefs at night and had held lanterns high

on poles to confuse pilots into navigating vessels onto the coral reefs. Natives would then plunder the wrecks. As a result, many Key West merchants sold a

large variety of exotic merchandise from such wrecked ships. Wrecking ships, recovering the cargo and

selling it resulted in a thriving business in old Key West.

These

stories gave young Lunn a good sense of the value of accurate navigation. He became obsessed with the importance of

being able to navigate by the stars as a means of maintaining an accurate

course on the sea. He studied the

stars, and he studied navigation books until spherical trigonometry became

commonplace as he worked to master his favorite subject. His diligence in learning the ways of the

sea qualified him to be captain of his own ship at the age of 26.

In

the early 1930s, an important part of the P & 0 Steamship Company's

business was hauling trains from Key West to Havana. Cubans loaded the trains with sugar. P & 0 ships then transported the railroad cars laden with

sugar back to Key West. From there they

traveled on the railroad across the Florida Keys to US markets.

In

Havana, Charlie met two people who changed his life forever. The first was an attractive, green-eyed,

blond, English girl who worked as a secretary for the P & 0 office in

Havana. After a year-long romance with

the handsome young sea captain, she became Mrs Charles J. Lunn. The other person to change his life was

Patrick Nolan, a captain for the Pan American Airways Company.

When

Pan American pilots moored their flying boats in the Havana Harbor, they were

generally near the P & 0 steam ships.

It was a custom for aircrews to go aboard the ships to visit and enjoy

good, well-prepared American food. It

was on such visits that Captain Nolan became acquainted with Charlie Lunn and

his expertise as a celestial navigator.

“Why

don't you come up to Miami and make an application for a job as a navigator

with Pan American?" Nolan asked Lunn.

Lunn said that he would have to

think about it for a while. He did

think about it. In 1935 a disastrous

hurricane swept across the Florida Keys destroying the rail line that had

previously brought the trains to Key West.

The P & 0 lines moved their operation from Key West to Fort

Lauderdale. It was then that Charlie

made up his mind to apply for a job as a navigator with the Pan American

Airways Company in Miami.

At

that time, Pan American was extending its aerial routes to distant cities of

the world. Among the first people to

navigate Pan American's big flying boats to such distant places were Charles J.

Lunn and Fred Noonan. The latter name

is indelibly written in aviation history as the navigator who accompanied

Amelia Earhart on her ill-fated effort to fly around the world. Although Charles J. Lunn is less well known,

he had navigated the big Pan American clippers for five years before his

fateful meeting with Gen Delos Emmons.

Classes

began on Monday, 12 August 1940, with Charlie Lunn as the chief performer. He stood pleading with his fledgling cadets

to understand the complicated procedures that he was explaining. There were no teachers' manuals. He was teaching what he had learned at sea

and then modified so he could navigate flying machines. Great minds like Nathaniel Bowditch, John Hamilton

Moore, Pytheas of Massalia, and many others had unlocked the secrets to using

the stars for navigation. Lunn was the

link between them and the thousands of young men who would be flying military

missions around the world using celestial navigation.

With

his fine six-foot physique, Charlie was a handsome figure in his Pan American

Airways uniform. However in the

classroom at the university, he often appeared in front of his class clad in a

round-neck, short-sleeved, knit shirt that exposed the brawny, tattooed arms of

a son of the sea.

"Don't write that down,"

he would plead. "You've got to get

it up here in your head. Your notes and

papers won't do you any good when you're out over the ocean some night."

Navigating over the ocean at night seemed more like a dream than a reality to

the cadets. None of us had ever been

"out over the ocean" in a plane at night. Nevertheless, Charlie doggedly transferred his grasp of celestial

navigation to his struggling students.

Little by little we became skilled at celestial navigation.

We received 50 hours of in-flight

navigation training flying from the Pan American seaplane base at Dinner Key. [2]

The base was located on the coast five miles from the university. There Pan American converted five of its

twin-engine Sikorsky and Consolidated flying boats into flying classrooms for

day and night training missions. There

were 10 large tables in each plane with maps of the Caribbean Sea area. Each table contained an altimeter, a

compass, and an airspeed indicator. A

large hatch open to the sky was used for taking celestial observations.

The Commodore, one of the five flying

boats used in training navigators

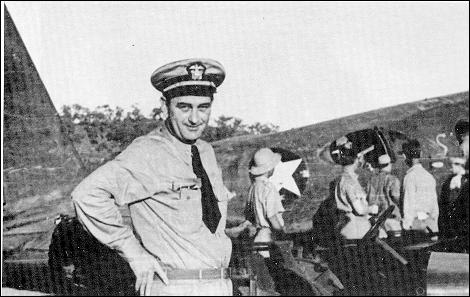

Charles Lunn

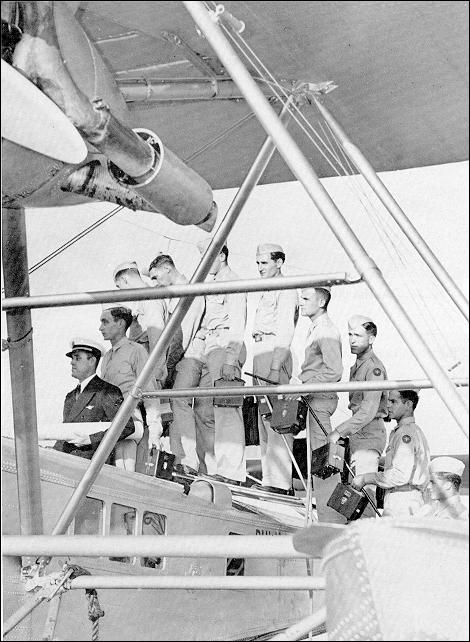

and cadets aboard a navigational in-flight trainer at Dinner Key, FL. Left to

right: Lunn, Trenkle, Arnoldus, Winter, Steig, Tempest, Thomas, Whitcomb,

Seamon, Dawson, and Markovich.

It

was said that the ancient flying boats would take off at 115 miles per hour,

cruise at 115 miles per hour, and land at 115 miles per hour. Cadet Harold McAuliff described the noise

the clipper made in landing as being like the sound of a truck dumping a load

of gravel on a tin roof. Antiquated as

they were, the planes provided a real-life environment for practicing celestial

navigation.

Before

a cadet set foot inside the big clipper training ships, he had to spend many

hours atop the San Sebastian Hotel at night.

There he got acquainted with the best friends he would ever have-the

stars and planets. Cadets learned the

names and the relative locations of the 50 brightest stars and the

planets. Betelgeuse, Arcturus, and

Canopus became as familiar as the names of the streets back in their hometowns.

In

the classrooms, there were "dry runs" across the Atlantic Ocean from

Miami to Lisbon, Portugal, and from Lisbon to New York. These were routes which Charlie Lunn had

flown many times. Charlie provided

columns of figures representing the altitudes of given stars in degrees,

minutes, and seconds. He also provided

columns of figures representing the hour, minute, and seconds of each

observation. These were to be added and

averaged manually before using the almanac and tables to establish celestial

fixes along the course. Neither

averaging devices nor computers were in use at the time. Navigation was an exercise in mental

gymnastics that seemed to have no ending.

Academic training quickly revealed

that the plane's airspeed indicator did not really measure how fast the plane

was traveling. The compass did not tell

the exact direction the plane was traveling, and the altimeter did not mark the

actual altitude of the aircraft. As an

aircraft moves through the air, navigators have to make corrections for such

things as temperature, atmospheric pressure, magnetic variation, deviation,

precession, and refraction. These were

things that Charlie Lunn had learned for himself when he left marine navigation

and took to the air.

Days and nights of work and study

filled the cadets' lives. As busy as

they were the cadets found time for recreation at the beautiful Venetian

Swimming Pool and the then uncrowded and uncluttered Miami beach. There were University of Miami football

games at the Orange Bowl and dances under the stars at the Coral Gables Country

Club. In addition there were many

attractive coeds on the campus to keep company with the cadets in their various

activities.

Then after 12 short weeks of Charlie

Lunn's intensified navigation training, there came the November graduation

exercises held at the stately Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables. Forty-four cadets sat on the stage at the

graduation exercises. We listened to

speeches by Dr Ashe, Pan American Capt Carl Dewey, and Gen Davenport

Johnson. The general, resplendent in

his dress blue uniform, spoke for the US Army Air Corps. Several hundred invited guests attended the

ceremonies, but few family members of the cadets were present. The country was still in the grips of the

depression. Few people could afford the

trip from remote parts of the country even for such an important affair.

Gen Davenport Johnson, in his

wisdom, spoke of the future and of our mission. “Time is of the essence," he said. "Our Air Force will be called upon to operate over much

larger ranges than is the case in European operations today. If the United States should become involved

in the present world turmoil and be forced to defend the Western Hemisphere, we

must be able to reach out from our coastal frontiers to discover, locate, and

destroy the enemy before he can get in striking distance of vital objectives

within the United States." {5}

On that happy and peaceful night in

Florida surrounded by the luxury and grandeur of the stately Biltmore Hotel and

the music of the university band, General Johnson, even with a prophet's mind,

could not have understood the significance of the event. In the months ahead, Charlie Lunn's 44

cadets would be navigating missions of inestimable significance. Passengers on their planes would include

such luminaries as Sir Winston Churchill, Madame and Generalissimo Chiang

Kai-shek, Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S Truman,

Dwight Eisenhower, and Lyndon Johnson, and Generals Douglas MacArthur, George

C. Marshall, and Curtis E. LeMay.

Within

one year, instead of defending our shores, many of us would be navigating

across the world to "locate and destroy the enemy." Classmates would

fly combat missions on every battlefront in World War II: in the frigid

Aleutian Islands, across the sand-blown deserts of North Africa, in distant

Rangoon, Saipan, and Gennany. They

would navigate on the first aerial attack on Japan and later with the B-29s bum

Japanese cities. They would 'seek out

and destroy" V-1 and V-2 launching pads and submarine pens on the

continent of Europe and help soften up the beaches of Normandy for the D day

invasion. They would be prisoners of

the Japanese and the Germans, and internees of the Turks. They would help in the project to dig the

tunnel for the great escape from Stalag Luft III in Germany. They would travel the brutal Bataan Death

March and lose classmates in the horrible Japanese prison camps.

At

the commencement exercises of the celestial navigators of the Class of 40-A,

General Johnson could have said, 'These navigators will follow the stars on a

path of tragedy and glory unique in the annals of American military

history."

Notes:

{1} The

Pan American-run school at Coral Gables was a short-run solution to the sudden

and massive growth of demand for trained navigators in the Army Air Corps (AAC)

(known after July 1941 as the Army Air Forces [AAFI). By late 1941, the AAF was meeting that demand with graduates from

three navigation schools of its own located at Kelly Field, San Antonio, Texas;

Mather Field, Sacramento, California; and Turner Field, Albany, Georgia. By the time the Japanese attacked Pearl

Harbor, the Pan American facility at Coral Gables was largely given over to

training fledgling navigators for the Royal Air Force. The best scholarly account of aerial

navigation down to World War II is Monte D. Wright, Most Probable Position: A History

of Aerial Navigation to 1941 (Lawrence, Kans.: University Press of Kansas,

1972). The relatively brief existence of the Pan American facility as a

training school for AAC navigators is noted on page 189.

{2} Army Air Forces, 'Flying Training Command

Historical Reviews," 1 January 1939-30 June 1946, held by Historical

Research Agency, Maxwell AFB, Alabama.

{3} Ibid.

Prior to World War II, the Army Air Corps had no school dedicated to

training aerial navigators and Monte Wright in Most Probable Position, 175, describes pre-World War II navigation

training in the AAC as .neither lengthy nor rigorous." In fact,

specialized officer aircrew members were unknown in the prewar AAC and

navigators, as a distinct group of rated aviators, simply did not exist. All flying officers were pilots, some of

whom might be called upon to perform navigator functions. Aerial navigation was considered just

another flying skill that some pilots were expected to master. The most ambitious AAC training program for

pilot-navigators was instituted in 1933 when the 2d Bomb Group at Langley

Field, Virginia, and the 7th Bomb Group at Rockwell Field, California, offered

standardized navigation courses to pilots drawn from units across the Air

Corps. The program was cancelled the

following year, a casualty of limited resources and the Air Corps' costly

involvement in government airmail operations.

From 1934 until the establishment of the Pan American school at Coral

Gables, navigation training reverted to individual units where it was conducted

on a limited and more or less haphazard basis to meet local requirements.

{4}

Charles J. Lunn, interview with

author, 1980; and Office of the Chief of the Air Corps to Dr B. F. Ashe,

letter, subject: Pan American Navigation School, 24 July 1940.

{5} Pan American Airways, Inc., New Horizons, New York, December 1940,

11.

Chapter

2

Prelude

to War

Upon graduation, I (Ed Whitcomb) was

assigned to March Field at Riverside, California, along with 17 of my

classmates. Eight class members were

assigned as instructors at newly established Army Air Corps navigation

schools. The other members were

assigned to Fort Douglas near Salt Lake City, Utah.

From

the moment we reached California, life took on new meaning. March Field opened up a world of exciting

adventures for young officers who enjoyed peacetime life in the glamorous

environment of southern California with nearby Hollywood and Palm Springs. The base was laid out beautifully with

Spanish-style buildings on streets lined with tall palm trees. Landscaping seemed immaculate.

March Field was undoubtedly the most

glamorous US military base. Army

officers commonly were seen in company with movie celebrities while attending

dances and other social functions at the Officers' Club. We were entertained by Bob Hope in his very

first performance for the military forces.

At another program, Tony Martin, a well-known singer, sang to the

accompaniment of Jerome Kern, the great composer.

Though

the navigators had a feeling that the US would soon become involved in combat,

military duties were in the tradition of the peacetime Army. Excerpts from letters I wrote home to my

mother illustrate the kind of life we led.

Prelude to war, girls from the

Florentine Gardens Los Angeles.

Left to right: Clark, Richards,

Whitcomb, Zubko, and Sheean

12 December 1940

Dear Mother,

We have been living a leisurely life

up to now. We report to the squadron at

8:00 o'clock each morning and attend classes on an average of about an hour and

a half a day.

19 December 1940

Have been working on a film with

Warner Bros. Pictures for past two days

as a technical advisor in a short that they are filming here "Wings of

Steel. . . ." Last night they invited me to a big party at the old Mission

Inn in Riverside.

2 February 1941

Movie actress Gail Patrick was there

last night with one of my friends.

Tyrone Power was over at the club yesterday afternoon while I was

there. Next Sunday there is going to be

a big blow-out at the club at which all of the Riverside Debs will be

presented.

B-17D Flying Fortress, first bomber in

action

11 February 1941

I think that I told you that I had

joined the Victoria Country Club. They

have the prettiest golf courses there that I have ever seen in my life. The grass is so green and the snow capped

mountains in the background make a beautiful picture. We have been playing just about every afternoon.

The high brass seemed oblivious to

the fact that Japanese and German airmen, our most likely adversaries in the

event of war, were flying daily combat missions against our potential

allies. The most serious efforts of US

bombardment crews at the time were conducting training missions which consisted

of dropping bombs at targets on Muroc Dry Lake (later Edwards Air Force

Base). For the most part, there were

cloudless skies where visibility was unlimited and there were no enemy fighters

or antiaircraft fire to distract the

flight crews. All pilots were checked

out as celestial navigators and expert bombardiers. To qualify as an expert bombardier, it was necessary to score as

follows:

|

Altitude of

flight |

Permissible

error |

|

5,000 feet |

75 feet |

|

10,000 feet |

150 feet |

|

15,000 feet |

225 feet |

Gunnery practice for aircrews

consisted of firing machine guns at a sleeve towed parallel to the line of

flight of the gunners by an obsolete B-18 aircraft. These mock combat activities continued from November 1940 until

April of 1941. Then conditions began to

change as indicated by more letters home.

7 May 1941

Dear Mother,

For the first time since I have been

here at March Field, I actually find myself so busy that I hardly have time to

write. With 8 new Flying Fortresses in

our squadron they have really kept us busy calibrating the instruments.

12 May 1941

Well this is the eve of one of the big

moments in this dull life of mine.

Cannot tell you; but I'm sure you will love it.

18 May 1941

This is Hawaii and it is great. We flew up to San Francisco last Tuesday

morning. At 10:20 p.m. Indiana time, we

passed over the southern tip of the Golden Gate Bridge and plunged into the

darkest, blackest night you have ever seen.

First, before we lost sight of the mass of lights of San Francisco and

Oakland, powerful searchlights from the anti-aircraft batteries along the coast

played on our planes bidding us a final farewell from the mainland.

We climbed through a rain squall

which hung just out of San Francisco Bay and finally broke out into the clear

at 10,000 feet to find our old friends, the stars, waiting to guide us across a

couple thousand miles of water to our destination.

Our flight, as you may already know,

was a mass armada of new Flying Fortresses which we were delivering to the Army

here-the greatest mass flight the Army has ever made.

Next Tuesday we will be sailing home

on the USS Washington. I understand it

is one of the finest ships on the seas these days. I also understand that the wives and daughters from the

Philippines are being returned to the States on the same boat.

28 May 1941

Aboard the USS Washington We heard

FDR's speech last night .... Looks as if we are well on the way toward war ....

This trip has put me closer to wartime conditions than I have ever been before

with the war maneuvers in Hawaii and all of the refugees on this boat. In Hawaii the Air Corps was on 24-hour alert

while we were there, and they were being called out at all hours of the night

and day to perform mock battles.

On

the trip back to the United States at a special meeting aboard the USS

Washington all aircrew members were invited to volunteer for duty ferrying

military aircraft from Canada to the Royal Air Force in England. All of the March Field crews volunteered,

but few were called for ferry duty.

By

the summer of 194 1, the Japanese had been at war with China for more than four

years in an effort to expand Japan's influence in the Far East. Newspapers and radio commentators reported

that Japanese troops had crossed the border of Indochina. In July the US cut off oil shipments to

Japan. The cutoff was serious because

the Japanese were buying more than 50 percent of their petroleum products from

the US. They needed gasoline and oil to

carry on their military operation.

War

clouds were gathering over the Western Pacific when Gen Henry ("Hap")

Amold, chief of the US Army Air Corps, ordered a study of the defenses of Oahu,

the Hawaiian Island occupied by Pearl Harbor and the all important Hickam

Field. The report delivered to the

general in August 1941 was entitled, "Plan for the Employment of

Bombardment Aviation in the Defense of Oahu." The report was uncanny. It predicted that the Japanese probably

would employ a maximum of six aircraft carriers against Oahu. Then, as if by some premonition, on page

five a statement was underlined for emphasis, "an early morning attack is

therefore, the best plan of action to the enemy." {1}

The

report also stated that a minimum of 36 B-17 bombers would be required to disable

and destroy the aircraft carriers. The

report recommended that 180 bombers be allocated to Hawaii immediately. We returned to our home station at March

Field. Then in September 1941, just

four months before the beginning of WWII, we were ordered to Albuquerque, New

Mexico. There we made preparations for

a special mission of the 19th Bombardment Group to go to the Philippine

Islands.

The

leader of the bombardment group was an outstanding aerial commander by the name

of Col Eugene L. Eubank. Lean and

erect, his first interest had to do with the welfare and military capabilities

of the men in his command. At March

Field he had been known to traipse from squadron to squadron checking on the

navigational proficiency of his flying officers. He was concerned that his pilots as well as navigators knew

celestial navigation.

His own background went deep into

the history of the Air Corps. A member

of the first class of flying cadets at Kelly Field, Texas, he remained as an

instructor because of his outstanding ability as a flyer. That was even before he was commissioned as

a second lieutenant. Later, he served

as chief test pilot for the Air Corps Experimental Division at Dayton,

Ohio. There he was friends with Orville

Wright and Charles A. Lindbergh. Like

them he was a true pioneer in aviation.

After that he commanded the Institute of Technology at Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas, before attending the Army's Command and General Staff School. Nobody was better qualified to lead the

first US air unit into combat in WWII than the man we affectionately referred

to as "Pappy" Eubank.

My next letter home was written

aboard a new B-17D Flying Fortress as it approached Hawaii en route to the

Philippine Islands.

18 October 1941

Dear Mother,

Oh, boy! Oh, boy! Oh, boy! There she is. Yep, old Hawaii just peeked over the horizon and you cannot

imagine how happy I am about the whole thing.

We have been in the air 12 hours now and in another hour we'll be

bouncing into Hickam Field.

25 October 1941

This

is Wake Island. We had a pleasant flight from Midway

yesterday... tonight we will set sail for Port Moresby, New Guinea, better than

a thousand miles below the equator.... By the time you get this, I should be in

my new home in P.I. Hope it is a nice place to live.

Less than one year after Gen

Davenport Johnson's speech at our graduation, 14 of us (Jay M. Horowitz, George

Berkowitz, John W. Cox, Harry J. Schreiber, Walter E. Seamon, Jr., William F.

Meenagh, Anthony E. Oliver, Harold C. McAuliff, George M. Markovich, Jack E.

Jones, Arthur E. Hoffman, Charles J. Stevens, William S. Warner, and I) were

far from America's "coastal frontiers." We were on Clark Field in the

Philippine Islands, 7,000 miles from United States shores.

Each

of us had navigated the broad Pacific Ocean from San Francisco via Hawaii,

Midway Island, Wake Island, Port Moresby, and Port Darwin. It was a glorious flight virtually without

incident. We had used all the procedures

and techniques that Charlie Lunn had taught us and developed some of our own. The trip was the greatest mass flight of

aircraft in history up to that time.

Our 26 shiny new B-17 Flying Fortresses fresh from the Boeing factory in

Seattle brought the strength of heavy bombers at Clark Field to 35.

Manila Hotel

1 November 1941

We have been here (Philippines)

several days and have found the place a nice place to live. From the hotel window here where I am

writing, I have a beautiful view across a golf course to the walled city of old

Manila.

We don't know when this war will begin

and no-one seems to care a lot.... You probably, know a lot more about what's

happening than we do.... Before you get this I'll be 24.

21 November 1941

We don't have any more idea what

might happen here than the next guy.

All I know is that they seem to be preparing for the worst with boatload

after boatload of planes, tanks, fuel, and men arriving all the time. Heard yesterday that three more squadrons of

bombers were due to arrive.

The

new environment in the Philippines was a world apart from anything we had ever

known. It was November 1941, and the

threat of war was in the air. Everyone

knew that but there was little or no talk about what it would be like if war

erupted. Sometimes I tried to visualize

what it would be like in the Flying Fortress high up in "the Wild Blue

Yonder." There would be enemy aircraft firing machine-gun bullets at the

plane and enemy antiaircraft shells coming at us. I suspected and hoped that our planes would fly so fast and so

high that no enemy planes or antiaircraft fire could reach us. I did not know that for a fact because there

was no experience upon which to base such a judgment. To my knowledge it was a matter that other crew members did not

discuss.

Never

before in the history of our country had we used heavy bombardment planes

against an enemy. There were many

things that we did not know. One thing

that we did know was that war with Japan was near. Yet when war would erupt was vague in our minds. It seemed remote to the point of being

unreal that such a thing would happen.

We

all knew of the exploits of Capt Eddie Rickenbacker and others in World War 1.

That was a long time ago and a different kind of war. This war would not be like the aerial warfare of World War I. Our

planes would have a crew made up of specialists including pilots, navigator,

bombardier, crew chief, radio operator, and gunners. Besides having the newest and finest of heavy bombers, we had the

supersecret Norden Bomb Sight. Rumor

said that it was so accurate that the bombardier could drop a bomb in a pickle

barrel from 20,000 feet. We also knew

that our pilots were the finest in the world because of the high standards of

qualification and training in the United States Army Air Corps.

We

gave little thought to the fact that Japanese pilots and aircrew members were

seasoned veterans in aerial warfare.

Our position was different. Not

one of us had ever been on a real, live bombing mission or engaged in any aerial

warfare against an enemy.

While we were getting acquainted

with our new environment, Maj Gen Lewis H. Brereton, General MacArthur's newly

assigned air commander, called all the aircrew members together for a meeting

at the base theater. There he told us

that the international condition had grown worse and that we might be involved

in war as early as April 1942.

There

were grandiose plans for beefing up the aerial strength of the Philippines

because the War Department was committed to an all-out effort to strengthen the

air defenses of the islands. With all

the good intentions, the air defense turned out to be a matter of much too

little, much too late. War was much

nearer than anyone had expected. We

would soon learn whether our mighty B- 17s would fly higher and faster than any

Japanese planes and whether our supersecret bomb sight would live up to its

reputation.

On

the night of 6 December 1941 more new B-17s were on their way from Salt Lake

City to join us in the Philippines.

Navigating

the planes were Louis G. Moslener, Jr., Richard Wellington Cease, Merrill K.

Gordon, George A. Walthers, Robert A. Trenkle, Paul E. Dawson, and Russell M.

Vifquain, Jr., but not one of them reached the Philippines. The following chapters relate their stories.

Notes

{1} Hearings before the Joint Committee on the

Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 79th Cong., 1946, 33/883

(unpublished).

Chapter

3

Death

on a Bright Sunday Morning

The Army Air Corps assigned Louis G.

Moslener, Jr., to Fort Douglas near Salt Lake City, Utah after graduation from

navigation school. Accompanying him on

that assignment were his classmates, Frediick T. Albanese, Robert T. Arnoldus,

Charles G. Benes, Carroll F. Cain, Richard W. Cease, Melvin Cobb, Paul E.

Dawson, Jr., Merrill K. Dawson, Jr., Edmund A. Koterwas, Edward L. Marsh, Leroy

L. Tempest, Barry P. Thompson, Robert A. Trenkle, Russell M. Vifquain, Jr.,

George A. Walthers, and James F. Wilson.

In Salt Lake City, Moslener took quarters off the military base in the

home of Mrs Margaret Powell. Joining

him there was Richard Cease, a fellow Pennsylvanian from Trucksville in the

eastern part of the state near Wilkes-Barre.

Moslener's hometown was Monaca, a small town north of Pittsburgh.

The genial Mrs Powell made her

residence a home away from home for "her boys." But the homelike

environment was not for long because secret order code name "Plum"

called for the movement of a large number of heavy bombers to the Philippine

Islands. All available navigators would

be needed to guide them across the sea.

On 5 December 1941 at the first

light of dawn a tiny, dark mound pushed up from the distant horizon across the

water. It was a welcome sight for Louis

G. Moslener, Jr., because he was navigating on his first long, overwater

flight. As a member of a crew of 11

airmen, he was on his way to the Philippine Islands. The long trip would take him to the romantic islands of

Hawaii. For almost 12 hours the big

B-17 Flying Fortress had been plowing through the black of night about 8,000 feet

above the Pacific Ocean.

I knew the trip well because I had

made it twice. Louis would have been

weary from the long night of seeking out stars, taking celestial fixes and

plotting them on his chart. Sometimes

the stars would have been elusive and would seem to dance in the field of vision

of his octant. At other times, they would

be blotted out by a cloud in the middle of taking an observation. Then there had been times when the

turbulence of the air caused the plane to be so unsteady that celestial

observations were difficult and even impossible. He had overcome the elements and felt good because that little

hump on the horizon told him that his navigation had been accurate. The flight was approaching Hawaii, the first

stop on their way to the Philippines.

Later a couple more mounds appeared on the distant edge of the ocean. He was able to identify them as the islands

of Maui and Oahu. His destination was

Hickam Field on the island of Oahu adjacent to the giant naval base of Pearl

Harbor.

As

the sun rose behind them, it became a bright sunny morning. It was an exhilarating feeling for Louis as

his B-17 descended toward the island of Oahu and his pilot, Ted S. Faulkner,

prepared for landing at Hickam Field.

Louis hurriedly folded his navigational charts and packed away his

equipment so he could drink up the scenery spread out before him. In a matter of seconds the plane would be on

the ground.

The

navigator's compartment, being in the Plexiglas nose of the aircraft, gave the

young navigator a panoramic view of the beautiful island and everything on

it. He saw the white rim of the waves

lapping lazily along the shore and hills green with tropical foliage. Then there were the long runways of Hickam

Field and the giant Navy base at Pearl Harbor clogged with warships. Hawaii was a beautiful and exciting place

that sunny morning.

Moslener

knew that there was a great urgency for getting B-17 bombers to the Philippine

Islands. There had been little advance

notice, but he was well prepared and ready.

He did not know that relations between the US and Japan had reached an

impasse or that Japanese warships were steaming toward Pearl Harbor even as his

plane was descending toward Hickam Field.

By

a strange quirk of fate, the Japanese admiral who masterminded the attack did

not favor going to war against the United States. Japanese extremists hated Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and considered

him pro-American. He had attended

Harvard University, served as a naval attach6 in Washington, D.C., and had

regularly attended American League baseball games at Griffith Stadium in

Washington, D.C. He had a healthy respect for American war potential.

In

compliance with Admiral Yamamoto's plan, six aircraft carriers were steaming

toward Hawaii at the time Moslener's plane was landing. The wheels of the plane touched the ground

and the first leg of the long flight had been successful. The crew was safe in the romantic Hawaiian

Islands. But there would be little time

to visit. After a rest and inspection

of the aircraft, the crew would be moving on to Midway, Wake Island, and the

Philippines.

Then came Sunday morning. If he were back home in Monaca,

Pennsylvania, Moslener would have been getting ready for Sunday school at the

Presbyterian Church with his mother and father. He had not been able to tell them that he was on the way to the

Philippines because of the secrecy of the mission.

A few days earlier he had written to

them telling them that he was "going on a long journey." Then he had

added, "but please don't worry." In his mind there was nothing to

worry about because he knew that many of us had made the trip to the

Philippines safely. However, his

parents did worry as all parents worry about their children in military

service.

People

in Monaca knew Moslener's father well.

He was a civil engineer and president of the local public school board. When people in the community asked about

young Louis, his father was happy to tell them that Louis was a 2d lieutenant

in the Air Corps and a navigator on a B- 17 bomber. Although Louis had earned his wings in the Air Corps, his friends

and neighbors could not think of him that way.

They remembered him only as the skinny, blond-headed young fellow who

had been active in church work, in the Young People's Forum, the DeMolay, and

in the high school band. It was hard

for them to relate the young boy they had known to a six-foot, 160-pound,

23-year-old officer in the Army Air Corps.

Hanger 15 at Hickam Field following

the 7 December 1941 attack

Early Sunday morning on 7 December

Moslener and his crew met at hangar 15 at Hickam Field. They were there to take their plane on a

short check flight before the next leg of their long journey. Without any warning there was a terrific

bomb explosion near the comer of the hangar next to the railroad track. The crew members except Moslener scattered

seeking protection. Moslener lay dead

on the hangar floor.

Just

48 hours before the bomb fell his mother and father had opened the letter from

Louis saying Louis was "going on a long journey." The next message

his parents received was a letter from his commanding officer, Maj Richard H.

Carmichael (later Major General), saying

Men died and are dying that peace may

be the lot of those they love. One of

the men who gave his life in the sudden attack here on the morning of December

7th was your son, Louis Gustav. He was

killed instantly by the first bomb dropped by the Japanese in this war. {1}

World War II had begun for the

United States. Louis G. Moslener was

the first but not the last of our classmates to make the supreme sacrifice for

his country.

Notes

{1} The Dallas

Post, Dallas, Pennsylvania, Friday, 3 April 1942.

Chapter

4

Attack

on Clark Field

Several hours passed after the

attack on Pearl Harbor before US personnel stationed in Clark Field learned of

the Japanese attack. Along with other

crew members, I (Ed Whitcomb) showered, dressed, and headed out into the

sunshine of a bright new Monday morning.

I was on the way to breakfast at the mess hall a block away. It seemed that it would be just another day

of preparing to go to war until somebody said, 'There is a rumor that the

Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor."

Following

that there was some discussion ridiculing the idea. It made no sense whatsoever.

US bases in the Philippines were much closer to Japan than Hawaii. Why would the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor

and leave Philippine bases with their fleet of bombers ready to attack the

island of Formosa?

Then

we heard a radio from one of the nearby barracks. It was Don Bell, the well-known voice of the news from Manila,

reporting, "The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor!"

We

had no way of knowing of the extensive damage the Japanese had inflicted upon

Pearl Harbor; nor did we know that our friend and classmate, Louis Moslener,

had been a victim of that attack. I

went directly to the 19th Group Headquarters.

It was an old two-story frame building facing the airfield where I had spent most of my time since our arrival in the

islands. My job had been sorting maps

and taking inventory of our navigation equipment.

Our

commander, Col Eugene L. Eubank, had learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor

early in the morning. He had rushed to

Manila to seek permission for us to carry out a bombing mission on the Japanese

airfields on Formosa, 500 miles to the north.

It seemed strange that he needed to ask for permission. We could not understand why we could not

attack the enemy. We waited for the

colonel's return. In the meantime

everything was at a standstill in headquarters. My most important priority appeared to be to get to the mess

hall. It might be a long time before we

would have another chance for a decent meal.

I hurried along the long, tree-lined walk to the mess hall. Across the field our planes were poised and

ready to go. We could be in our B- 17s in two minutes when we got word to

go. We were ready.

Flyers

crowded the mess hall to enjoy generous portions of breakfast with tall glasses

of pineapple or orange juice or whatever a person cared to eat or drink. After a hurried meal, I anxiously made my

way back to the headquarters.

There

pilot Edwin Green asked me to make certain that our B- 17 cameras contained

film for an aerial reconnaissance mission.

A driver delivered me to the plane in seconds. Seeing that there was no film, I hurried to a supply tent within

easy walking distance and picked up the film after first signing the

appropriate receipt. However, when I

stepped outside the tent, I discovered that my plane had taken off! It seemed

to have vanished almost before my eyes!

I learned that during the short time I had been in the supply tent, a

field alert caused almost all flyable planes to leave the ground.

Back

at headquarters, I busied myself sorting maps until Colonel Eubank returned

from Manila and called a meeting. We

assembled on the street in front of the headquarters building at about 1030. There the colonel reported the bewildering

news that he had been unable to get authority to fly a bombing mission. He had gone to the headquarters of Maj Gen

Lewis H. Brereton, commander of the Far East Air Force (FEAF). [3]

General Brereton, the top Air Corps officer in the Philippines, had not been

able to see General MacArthur. Brereton

talked to Gen Richard K. Sutherland, MacArthur's chief of staff, who ordered

three B-17s to fly reconnaissance missions to Formosa but did not authorize a

bombing mission.

Still

nothing happened. We waited and

speculated. We had no way of knowing

that fog covered the airfields at Formosa that morning, nor did we know that

there were some 600 planes on the ground there. Had we been able to fly a reconnaissance mission to Formosa that

morning, it is certain that we would have received a warm and overwhelming

reception.

The long worrisome morning whiled

away and again I hurried to the mess hall for a quick meal. As I departed the hall, George Berkowitz, a

classmate and fellow navigator, was just coming in for lunch. He reported that nothing had changed at

headquarters.

Suspense filled the air, yet we felt

helpless. There was no question that

America was at war. We all wanted to

fly. We were ready.

There was no warning at headquarters

of Japanese planes approaching Clark Field.

Despite all our warning systems and all the reconnaissance missions we

had flown, the Japanese caught us by surprise.

The first notice we had at the 19th Bombardment Group Headquarters was when

someone screamed, "Here they come!"

At

that moment, the bombs were on their way.

I dove into a trench about 30 feet to the rear of the headquarters

building. Explosions rocked the ground

and sent shock waves through my body.

Other bodies crushed me to the dark bottom of the trench until my face

and body pushed into the pounding earth.

The explosions continued and the earth seemed to heave with each

blast. We learned later that there had

been two waves of 27 high-flying bombers each.

Bombs hit the officers' mess hall, many planes on the flight line, and

the hangar area. At the time I did not

know that Berkowitz had suffered disaster as he left the mess hall.

When

the bombers had done their damage and departed, we started to extricate our

bodies from the trench. Then the

staccato sound of machine-gun fire shattered the air. We quickly realized that Zero fighters were strafing the

field. Back and forth they flew, time

after time, raking the field and the hangar line with their deadly fire. Huge black clouds from burning planes and

the fuel supply dump blotted out the noonday sun as the planes continued their

destruction virtually unopposed.

With grime in my ears, eyes, nose,

and mouth, I struggled to get out of the trench when the strafing ended. The bombing and strafing attacks had been a

terrorizing ordeal. I was so shaken

that for a time I was uncertain of my own physical condition. The crackling sound of burning filled the

air along with intermittent explosions from the direction of the flight

line. I found Colonel Eubank beside the

headquarters building. He was witnessing the destruction of half of his bomber

fleet. {1}

Just

as I was ready to set out for the flight line to see the damage to our planes,

another flight of fighters streaked in across the field at treetop level. They were so low that the Japanese pilots

were plainly visible. Colonel Eubank

did not take cover. He stood helplessly

watching the enemy planes darting in and out, spraying the field with their

devastating fire and destroying the remainder of his B-17s on the field. When the last Zero finally departed the

area, Clark Field lay in ruins and the raid had killed more than 100 people.

We

had considered Clark Field to be at the very forefront if we were to be forced

to undertake an aerial offensive against the Japanese. Just two days before the Japanese raid, it

had been the proud home of 35 of the world's finest bombardment aircraft. Fortunately, at the time of the attack, 16

bombers had moved to Del Monte Field on the island of Mindanao more than 500

miles to the south. They were beyond

the range of the Japanese bombers based on Formosa and there was reason to

believe that the Japanese were unaware of existence of Del Monte Field. At any rate, the 16 planes at Del Monte were

safe from destruction on that disastrous first day of the war in the Pacific.

For

weeks after the beginning of the war, the dirt airstrip at Del Monte became the

most important base for air operations in the islands. Most of the aircrew members who reached Del

Monte Field were able to fly to Australia and avoid the prison camp life that

many of us suffered in the months ahead. {2}

Notes

{1} The first wave of Formosa-based Japanese

planes (54 bombers and 36 Zero fighters) attacked Clark Field at approximately

1220 on 8 December 1941. Although nine

hours had elapsed since MacArthur's headquarters had received news of the

disastrous events at Pearl Harbor, American forces at Clark were no better

prepared than those in Hawaii for a Japanese raid. During the 30-minute attack, virtually every building on the base

was destroyed or damaged, and hundreds of people were killed or wounded. Flights of Zeros made multiple strafing

passes as the bombers departed. Only

four P-40s managed to get airborne in a hopeless effort to engage the

high-flying Japanese bomber force.

Virtually every B-17 on the base-two squadrons' worth-was either

destroyed or badly shot up. The same

fate befell an entire squadron of P-40 fighters.

Exactly what transpired in the

discussions on the hectic morning of 8 December between General MacArthur, his

chief of staff, Maj Gen Richard K. Sutherland, and Major General Brereton, has

never been resolved. All three men

later gave conflicting accounts. What

does seem clear is that over a five- or six-hour period, Brereton made three

attempts to see MacArthur, presumably to gain permission to launch a preemptive

B-17 raid against Japanese air bases in Formosa. In each case, the imperious Sutherland denied Brereton access to

MacArthur. Sometime between ten and

eleven A.M. Brereton finally received the directive he sought. By 1120, orders to arm and fuel the B-17s

had been teletyped to Clark Field, but the American bombers were still on the

ground when the Japanese planes appeared overhead an hour later. Whether or not commanders at Clark Field

received adequate advance notice about the inbound Japanese force also remains

in dispute.

Altogether,

over the next four days, the Japanese conducted 14 major air raids against

various military and naval sites in the Manila and Clark areas. Always outnumbered, the FEAF steadily lost

more planes as aircrews mounted a desperate series of air defense efforts.

For a

detailed account of the debacle at Clark Field, see Wesley Frank Craven and

James Lea Cate, eds., The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 1, P@ and Early Operations, January 1939 to August 1942 (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1948-58), 203-10. A

judicious appraisal of the disaster is in D. Clayton James, The Years of MacArthur, 1941-1945, vol. 2

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975), 5-15.

Shorter and more recent summaries are in Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York: Free Press, 1985).

106-8. and Geoffrey Perret, Winged Victory: The Army Air Forces in World War II (New York: Random House, 1993), 78-81. General Brereton's recollections of this

event are in Lewis H. Brereton, The Brereton Diaries: The War in the Air in the Pacific, Middle East and Europe, 3 October 1941-8 May 1945 (New York:

William Morrow, 1946).

{2} Del Monte Field was an unimproved landing

strip on a narrow plateau adjoining the Del Monte Corporation's pineapple

plantation on the northern shore of the island of Mindanao. Since Del Monte Field lacked landing aids

and was surrounded by 4,000 mountains, landing a B-17 at Del Monte in darkness

or bad weather constituted a test of skill and nerve even for seasoned Fortress

pilots. In anticipation of eventually

basing his entire heavy bomber fleet on Mindanao, General Brereton had sent two

B- 17 squadrons (16 aircraft) and a small number of B-18s to Del Monte in early

December 1941. The anticipated eminent

arrival of the entire 7th Bomb Group at little Del Monte limited the number of

planes Brereton could deploy from Clark Field. Craven and Cate, 187-89.

Landing a B-17 at Del Monte under adverse conditions is characterized as

a 'white-knuckle" experience in Perret, 78-79.

Chapter

5

George

Berkowitz

George Berkowitz reads letter from

home

If there had been a designation of a

Mr Congeniality in the Class of 40-A, it surely would have gone to George

Bemard Berkowitz. He was a

happy-go-lucky navigator from Dallas and the University of Texas. George was unquestionably the most colorful

and popular member of the class. He was

a big, well-proportioned 175-pound fellow.

His 6'2' frame was topped off by a crop of sandy hair with a reddish

tinge. A few freckles were randomly

sprinkled across his face. He liked

well-tailored clothes and big cigars.

The

scowl on George's face belied the fact that the imps of devilment were dancing

in his head. He was totally

undependable in conversation. In the

middle of a serious discussion he might pull out a big cigar, light it, and

turn on his heels with a comment like, "Don't bother me now. Can't you see I have a lot of important

things on my mind?"

Those

of us who knew him knew that it was all in jest and in the nature of an act he

played continually. With him it was

always the unexpected. He might borrow

money from a friend then take him out to dinner. However, he was prompt to repay his debts on payday.

On

one occasion when his plane was high over the western Pacific, Saint Elmo's

fire enveloped his aircraft. That is a

condition when a fiery glow develops over the exterior of the plane while in

flight. It is temporary and not

dangerous. Being unfamiliar with it,

Berkowitz became alarmed. It alarmed

Berkowitz until his pilot, Col Bert Cosgrove, explained the phenomenon to him.

In

mock seriousness Berkowitz asked, "Can you tell me where I can catch the

first bus back to Dallas?" With all his eccentricity, George was serious

about his job as a navigator. Like

other members of our class, he had successfully brought his bomber across the

Pacific. Since then we had been in the

Philippines learning about life in the Orient and getting prepared for war.

George was having a hurried lunch in

the officers' mess hall where I (Ed Whitcomb) had eaten just 15 minutes

earlier. The officers about him engaged

in lighthearted banter concerning the report of a Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor. Why would they attack Pear

Harbor and ignore Clark Field which had a fleet of the finest bombers in the

world supported by squadrons of fighter planes? It had been almost seven hours since they had first heard the rumor,

yet nothing had happened at Clark Field.

There had been that false alarm of enemy planes approaching the

field. Our planes had taken to the

skies, but no one had sighted any hostile planes. Our airplanes returned to the base and were waiting for further

orders. The situation was

confusing. No one could understand why

we had not been ordered to fly a bombing mission.

Then

abruptly the mood changed. A mighty

bomb blast rocked the mess hall followed by the roar of more and more

earth-shaking blasts. The mess hall had

received a direct hit. Panic set

in. Flyers rushed for the door, some

heading directly across the field to the flight fine two blocks away. There was screaming and moaning of civilian

workers and officers who had been struck by bomb fragments.

Berkowitz

was running across the field to his plane when a large chunk of bomb fragment

chopped him down. In a state of

excruciating pain and semi-consciousness, he realized that others had been hit

by bomb fragments. Then a second wave

of the high-flying bombers laid a second pattern of bombs across the field. Buildings

and planes were ablaze. After the

bombers had passed, fighter planes raked the field at treetop level darting in

and out of the black columns of smoke from bun-ling planes and the fuel dump.

As

George lay on the ground, he became aware that his leg was mangled between the

knee and the hip. He grew weak from the

loss of blood and feared that he would die before help reached him. He screamed for help, but his voice was

drowned out by the noise of explosions and machine-gun fire.

At

long last stretcher bearers appeared.

They loaded him into a vehicle and transported him to the nearby Fort

Stotsenberg Hospital. There, in his

faint condition, he received the devastating word that his leg would be

amputated between the hip and the knee.

There was no opportunity to ask

questions. In his dismal state of mind he wondered what

had happened? Did he really have to

lose his leg? Where were his other crew

members and his friends? What had

happened to them? What would happen to

him? Where was he going? He had no way of knowing.

Later

George was moved by railroad car to the Philippine Women's University in Manila

56 miles away. Under other

circumstances, he would have welcomed that environment. At that time the university had converted

its facilities into a hospital for wounded soldiers. It was hoped that they could be moved out of the war zone, possibly

to Australia. The only women Berkowitz

saw at the Philippine Women's University were the busy Catholic sisters who

kindly administered to the needs of the injured patients.

George languished in the hospital

for three weeks, while the Japanese continued bombing and strafing the city

about him. Then one afternoon there

came a surprise for George. He looked

up to see the smiling face of his commander, Col Eugene Eubank. The colonel had learned about him and had

come to comfort him. It was then that

George learned what had happened to his friends on that first day of the war.

Finally 248 wounded soldiers were

moved through the streets of Manila to the dock area. Col Carlos Romalo of General MacArthur's staff had finally

secured an ancient interisland steamer called the Mactan which the Army converted into a hospital ship for evacuating

wounded soldiers from the war zone.

George and the other wounded embarked on the 46-year-old ship for the

2,000-mfle ocean voyage to Australia.

The crew had painted a big white cross on each side of the ship and the

Red Cross flag hung from the main halyards.

As the Mactan left the docks, those on the upper decks could see huge