FP-1942AU-AugNov.DOC

Chronology

of Events August-November 1942

07-29-42 Gen Kenney reports to MacArthur replacing Gen Brett

08-01-42 Marines land on Guadalcanal.

08-26-42 Japanese land at Milne Bay

08-__-42 28th, 30th& 93rd Sqd move to Mareeba

09-13-42 Battle for Henderson Field at Bloody Ridge, Guadalcanal, Japanese held off

09-14-42 Australians push up Kokoda trail, Japanese hold at Iowibaiwa ridge

09-16-42 Australians set trap at Imita ridge and destroy enemy force.

09-21-42 Australians push Japanese back using (2) 25 pounders to break Iowibaiwa ridge defense. The tide has turned,

10-08-42 Marines counter attack Japanese assault on Henderson Field.

10-15-42 Aircraft from badly damaged Henderson impair Japanese landing.

10-25-42 Japanese force make arduous march and attack on Henderson Field, loosing 2000 men vs 200 marines.

11-14-42 Japanese ships shell Henderson Field.

11-10-42 19th BG returns to the US, 43rd BG takes over.

02-01-43 Tokyo Express goes in reverse removing troops from Guadalcanal region.

Change of

Command July 24, 1942

Extracted from “Gen Kenney Reports by Gen G. Kenney

Lieutenant General George H. Brett had been General Wavell's deputy in the now disbanded American-British Dutch-Australian Command. When the Japs ran the Allies out of Java in March 1942, Wavell had gone to India and Brett had taken over the Allied command in Australia. On MacArthur's arrival in that country a couple of weeks later, Brett, as the senior airman in the theater, became General MacArthur's Allied Air Force Commander. He had not had much to work with and his luck had been mostly bad. MacArthur's Chief of Staff, Major General Richard Sutherland, and Brett had seldom seen eye to eye on anything. Brett's own staff was nothing to brag about and that had not helped either. I had worked under Brett when he commanded the Air Materiel Division at Dayton a couple of years before and liked him a lot. I hoped they would give him a good job when he got back. General McNarney said he hadn't heard what Brett was lined up for.

I talked with McNarney at some length about the general situation. Europe was going to get the real play, with a big show going into North Africa that November to chase Rommel and his Afrika Korps out of the area before they grabbed Egypt and the Suez Canal on one of their tank drives.

The Pacific war would have to wait until Germany was disposed of before any major effort would be made against Japan. There simply were not enough men, materials, or shipping to run big-scale operations in Europe and the Far East at the same time, so the decision had been made to concentrate on defeating Hitler and to take care of the other job later on.

McNarney held out no encouragement that troops, aircraft, or supplies in any appreciable numbers or quantities would be sent to the Pacific for a long time to come. No wonder he wished me luck.

The next day General Arnold took me into General Marshall's office, where I was officially told about my new assignment. My instructions were simply to report to General MacArthur. Their analysis of the problems that I would be up against not only confirmed what I had heard from McNarney but sounded even worse. The thing that worried me most, however, was the casual way that everyone seemed to look at the Pacific part of the war. The possibility that the Japs would soon land in Australia itself was freely admitted and I sensed that, even if that country were taken over by the Nipponese, the real effort would still be made against Germany.

I gathered that they thought there was already enough strength in the Pacific, and particularly in Australia, to maintain a sort of "strategic defensive," which was all that was expected for the time being. Arnold said he had sent a lot of air planes over there and a lot of supplies, but the reports indicated that most of the airplanes were out of commission and that there didn't seem to be much flying going on. He said that Brett kept yelling for more equipment all the time, although he should have enough already to keep going. I was told that there were about 600 aircraft out there and that should be enough to fight a pretty good war with. Anyhow, while they would do what they could to help me out, they just had to build up the European show first.

General Marshall said there were a lot of personality clashes that undoubtedly were causing a lot of trouble. I said I knew of some of them already and that I wanted authority to clean out the dead wood as I didn't believe that much could be done to get moving with the collection of top officers that Brett had been given to work with. They told me that I would have to work that problem out with General MacArthur. I said I wished that they would wash the linen before I got out there and save me the trouble, but I didn't get to first base with the suggestion.

Luckily I would have two good brigadier generals to work with me as Ennis Whitehead and Ken Walker had already been ordered to Australia. I had known both of them for over twenty years. They had brains, leadership, loyalty, and liked to work. If Brett had had them about three months earlier, his luck might have been a lot better.

I stayed around Washington for three more days, absorbing all the data I could find in regard to the Southwest Pacific Area. I knew Arnold didn't think much of the P-38 as a fighter plane, so it wasn't hard to get him to assign me fifty of them with fifty pilots from the Fourth Air Force. I intended to make sure that a Lieutenant Richard I. Bong was one of the pilots.

Hap Arnold told me that Major General Millard (Miff) Harmon, who had been his Chief of Staff, had been ordered to the South Pacific Theater, where, under Vice-Admiral Robert H. Ghormley, he was to command all Army troops, air and ground. He was taking with him, to command his Army Air Force units, Brigadier General "Nate" Twining and several colonels. We would all go out together in a Liberator bomber that had been converted into a sort of passenger carrier. Sort of because they had dispensed with such luxuries as sound proofing, cushioned seats, heating system, or windows to look out of. It might not be very comfortable, but I preferred it to spending a month on a boat. According to the present schedule, we would leave on July 21 from San Francisco for New Caledonia, via Hawaii-Canton Island-Fiji. Miff and his gang would get off in New Caledonia, and Bill Benn and I were to have the plane to ourselves during the remainder of the trip to Australia.

Among the multitude of people that I conferred with about the arrangements for sending airplanes, engines, propellers, and spare parts to Australia to keep my show going, was "Bill" Knudsen, the former president of General Motors, who had been called into government service to speed up production of war materials, particularly through mobilization of the automotive industry of the country. I had had a lot of dealings with him during the past two years, and besides admiring his methods of getting things done, I had gotten very fond of him. We liked each other.

His ability in his field was unquestioned. His simple honesty, his sincerity, his unselfish patriotism, and his unfailing sense of humor endeared him to everyone. The country owed a lot to William S. Knudsen, who had been made a lieutenant general a few months previously, with the additional title of Director of War Production for the War Department.

Bill had just come back to his office from a long conference which had consisted of a lot of talk but no decision. In that charmingly thick Danish accent of his, he told me about it and then suddenly said, "George, do you know what a conference is?" I said, "Go ahead. I'm listening." He grinned, hesitated a little, and gave me his definition. I still consider it a gem. It still fits most of them. "A conference is a gathering of guys that singly can do nothing and together decide that nothing can be done." My favorite of all Bill Knudsen's sayings, however, came one day in Washington when we were Listening to an efficiency expert give us a lecture on speeding up the process of letting contracts to industry .In the course of the talk, he kept using the phrase, "Status quo." After about ten repetitions of the two words, Knudsen nudged me and whispered, "George, do you hear that `status quo' stuff?" I nodded. Bill waited a few seconds and continued, "That's Latin for what a hell of a fix we're in."

The day before I was to take off for Australia, I went over to General DeWitt's headquarters to say goodbye. He was very complimentary about my show under him and said how sorry he was to have me leave but that he knew how I felt about going to a real combat theater. and wished he were going with me. He showed me a message that he had sent to General MacArthur the day I had returned from Washington I and told him where I was going. The message read: "Major General George C. Kenney Air Corps has received orders relieving him from duty Fourth Air Force this command and directing him report you for assignment stop Regret to lose him but congratulate you stop He is a practical experienced flyer with initiative comma highly qualified professionally comma good head comma good judgment and common sense stop High leadership qualities clear conception of organization and ability to apply it stop Cooperative loyal dependable with fine personality stop Best general officer in Air Force I know qualified for high command stop Has demonstrated this here stop Best wishes."

DeWitt then grinned and said, "Now read this," and handed me MacArthur's slightly "I'm from Missouri" answer: "Personal for General DeWitt stop Appreciate deeply your fine wire and am delighted at your high professional opinion of Kenney stop He will have every opportunity here for the complete application of highest qualities of generalship stop Wish you and the Fourth Army could join me here we need you badly."

We both chuckled over it, shook hands, and wished each other luck for the duration.

At 9:30, the evening of July 21, with Major General Miff Harmon and his staff, Bill Benn and I took off from Hamilton Field, about thirty miles north of San Francisco, and headed west for Hickam Field, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands.

Shortly after daybreak the next morning we circled Pearl Harbor and landed at Hickam Field. While Pearl Harbor still showed the scars of the Jap attack of last December 7, with the Oklahoma still lying capsized on the bottom and the Arizona a tangled mass of twisted wreckage sticking up out of the water, the whole island of Oahu was bustling with activity. Both Army and Navy had certainly become "shelter" conscious. Everybody seemed to be digging in. Fuel storage tanks were being installed underground. A complete underground headquarters was in operation by the Army Air Force and a huge air depot and engine overhaul plant was being constructed by tunneling into the side of a mountain.

Hickam Field and Wheeler Field, the two Army airdromes at the time of the big Jap attack, still showed the effects of the disaster. Hangars, barracks and warehouses, burned and wrecked during the bombing, had not yet been rebuilt. There was no doubt about it, Hawaii had been in the war and, from all the digging going on, they had not forgotten it either.

When I asked about the news of the war out where I was going, I learned that, the day we left San Francisco, the Japs had made a new landing on the north coast of New Guinea at a place called Band and had started driving the Australians back along the trail over the Owen Stanley Mountains toward Port Moresby. MacArthur's communiqué spoke of the landing being opposed by our aircraft, which had sunk some vessels but had not stopped the invasion. I figured that it probably meant more trouble for me. Anyhow I'd find out in a few days.

On the 24th, we flew to Canton Island and spent the night at the Pan American Hotel which had been taken over by the Navy, who had done a real job blasting a channel through the coral reef to get an anchorage for vessels and building an excellent flying field on the atoll itself. A squadron of Army Air Force P-39 fighters was stationed there for protection from Jap air attack, although the Nips had no airdromes within operating range. If an aircraft carrier should get close enough to threaten the place, this one P-39 squadron couldn't do anything about it except be the gesture of defense that it really was. As a matter of fact, if the Japs had really wanted Canton Island, they wouldn't have needed much of an expedition to take it. It was practically defenseless against any decently organized attack.

The next day we arrived at Nandi in the Fiji Islands about eleven o'clock in the morning. We taxied up in front of a hangar, stopped the engines, got out, and looked around to see if anyone lived in the place. We had been in radio communication, but there certainly was no welcoming party for General Miff Harmon, the new commander of the South Pacific Theater, which included Fiji. After about fifteen minutes, a young lieutenant hurriedly drove up in a jeep and asked for General Harmon. Miff identified himself and was handed a message from the colonel commanding the Nandi Base, saying that he would see him at mess at 12:30, as at the moment he was taking a sun bath. Miff handed me the note without saying a word. I read it and handed it back to him, also without a word. Miff put it in his pocket and said, "Let's go find where we are going to stay and where they serve that mess the colonel mentioned." I suspected that there would be a new commander there shortly.

Harmon's new command included an American Infantry Division, the 38th, which was relieving the New Zealand troops who were pulling out. We went over to their headquarters and got briefed on how they would defend the place if the Japs should try to take over Fiji. It sounded too much like the old textbook stuff to be very impressive. I didn't get the impression that they realized that World War Two differed radically from World War One. However, while we may get pushed around rather roughly at first, we generally learn fast. The bad thing about it is that, in war, it costs lives to learn that way.

To take care of the air situation, Harmon had a couple of P-39 fighter squadrons and two squadrons of B-26 medium bombers stationed at Nandi to defend the Fiji Islands, along with a few New Zealand reconnaissance planes which were helping out on antisubmarine patrol. It wasn't much more than a token force, at best.

So far, I had seen nothing to indicate that our air line of communication across the Pacific was very secure. Canton was wide-open and any one of the Fiji Islands could have been taken easily, including Viti Levu, the one that Nandi is on, and the only one defended at all. If either of these links in the chain were taken out, the air route would be gone and the ship distance to Australia increased by at least another thousand miles to keep out of range of Jap bombers that would then be based at our former Canton or Fiji airdromes.

We had excellent weather all the way from New Caledonia, which gave us a chance to appreciate the beautiful blue water of Australia's east coast and the startling green colors around the pink and white coral reefs offshore. The land itself made you feel at home. Here were well-kept farms and villages, beaches that looked as though they were used as summer resorts, and rivers with wharves and boats on them. After all the water, atolls, and jungle-covered islands I had seen for the past week I was glad to be arriving among people and civilization again.

We crossed the coastline, flew inland across the city of Brisbane, Australia's third largest city, sprawling on both sides of a river and looking to be about the size of Cincinnati, Ohio. with its multi-storied business district, apartment houses, and the outskirt fringe dotted with bungalow-type single houses, from the air it could have been any one of a dozen Midwest American cities.

Just before sundown, we landed at Amberley Field, about twenty miles west of Brisbane. As we got out of the airplane, a Royal Australian Air Force billeting officer at once took me in tow and in a few minutes I was on my way to town assigned to Flat 13 in Lennon's Hotel. Benn was also assigned there. It was explained that only the top brass and their aides lived there, as it was not only the best hotel in town but the only one that was air-conditioned.

The air-conditioned part didn't interest me very much as August is a winter month in Australia and, although it was only twenty-eight degrees below the equator or about the same distance south that Tampa, Florida, is north, the wind was chilly enough so that I was glad I had on an overcoat.

Flat 13, however, sounded all right. Although I don't claim to be superstitious, a lot of good things have happened to me with that number involved. Back in 1917 I passed my flying tests, which first entitled me to wear pilot's wings, on the thirteenth. I left New York to go overseas in World War I on that date; my orders sending me to the front were dated February 13, 1918 I shot down my first German plane on the thirteenth, and so on. That number on my door at Lennon's Hotel looked like a good start.

After dinner I spent a couple of hours talking to Major General Richard K. Sutherland, General MacArthur's Chief of Staff. I had known him since 1933 when we were classmates at the Army War College in Washington. While a brilliant, hard working officer, Sutherland had always rubbed people the wrong way. He was egotistic, like most people, but an unfortunate bit of arrogance combined with his egotism had made him almost universally disliked. However, he was smart, capable of a lot of work, and from my contacts with him I had found he knew so many of the answers that I could understand why General MacArthur had picked him for his chief of staff. I got along with him at the Army War College when we were on committees together and I decided that I'd get along with him here, too, although I might have to remind him once in a while that I was the one that had the answers on questions dealing with the Air Force. Sometimes, it seemed to me, Sutherland was inclined to overemphasize his smattering of knowledge of aviation.

It didn't take long for me to learn what a terrible state the Air Forces out here were in. Sutherland started out right at the beginning on December 8, 1941. He said that he advised General Lewis H. Brereton, the Air Commander in the Philippines at that time, to move his airplanes to Mindanao and that, as Brereton didn't do it, the loss of our planes on the ground to the Jap bombing and strafing attack was Brereton's fault. He claimed that, following the attack, our air officers and men were so confused and bomb-happy that the military police were busy for days rounding them up around Manila. He castigated all the senior air officers except Brigadier General H. H. George, Brereton's Fighter Commander in the Philippines, who was killed in May 1942 at Darwin, Australia, when he was hit by an airplane which swerved off the runway.

I had known "Hal" George ever since World War I. He was a good boy and, according to all the reports, he had been a thorn in the side of the Japs in the Philippines right up to the time he had gotten down to his last fighter plane. His loss by that unfortunate accident at Darwin was another piece of bad luck for George Brett.

The more I heard about those opening events of the war in the Philippines the more it seemed to me that the confusion that day had not been confined to the Air Force. These stories about everyone else being calm and collected were told and retold with so much emphasis that I began to suspect they were alibis.

Sutherland finally worked up to present-day conditions. Brett certainly was in wrong. Nothing that he did was right. Sutherland said they had almost had to drive Brett out of Melbourne when MacArthur's headquarters moved from there a couple of weeks previously to the present location in Brisbane. According to Sutherland, none of Brett's staff or senior commanders was any good, the pilots didn't know much about flying, the bombers couldn't hit anything and knew nothing about proper maintenance of their equipment or how to handle their supplies. He also thought there was some question about the kids having much stomach for fighting. He thought the Australians were about as undisciplined, untrained, over advertised, and generally useless as the Air Force. In fact, I heard just about everyone hauled over the coals except Douglas MacArthur and Richard K. Sutherland.

Come to think of it, he did say one thing good about the men of the Air Force. It seemed that up on Bataan, after all their air planes were gone and they had been given some infantry training, they made good ground troops....

This was going to be fun. Already it began to look like a real Number One double-shooting job.

The next morning I saw General Brett at Allied Air Force headquarters on the fifth floor of the AMP Building, a nine story Life-insurance building which had been taken over by Allied Headquarters and in which General MacArthur and his staff, together with the Air and the Navy commands, maintained their offices. We talked for a while and then I went up stairs to the eighth floor to report to General MacArthur. General Brett did not go with me. Sutherland said the "Old Man" was in, so I walked into his office and introduced myself. The general shook hands, said he was glad to see me, and told me to sit down.

For the next half hour, as he talked while pacing back and forth across the room, I really heard about the shortcomings of the Air Force. As he warmed up to his subject, the short comings became more and more serious, until finally there was nothing left but an inefficient rabble of boulevard shock troops whose contribution to the war effort was practically nil. He thought that, properly handled, they could do something but that so far they had accomplished so little that there was nothing to justify all the boasting the Air Force had been indulging in for years. He had no use for anyone in the whole organization from Brett down to and including the rank of colonel. There had been a lot of promotions made which were not only undeserved but which had been made by Washington on Brett's recommendations. If they had come to him, he would have disapproved the lot. In fact, he believed that his own staff could take over and run the Air Force out here better than it had been run so far.

Finally he expressed the opinion that the air personnel had gone beyond just being antagonistic to his headquarters, to the point of disloyalty. He would not stand for disloyalty. He demanded loyalty from me and everyone in the Air Force or he would get rid of them.

At this point he paused and I decided it was time for me to lay my cards on the table. I didn't know General MacArthur any too well as I had just met him a few times when he was Chief of Staff of the Army six years before, but if he was as big a man as I thought he was, he would listen to me and give me a chance to sell my stuff. If not, this was a good time to find out about it even if I took the next plane back to the United States. I got up and started talking.

I told him that as long as he had had enough confidence in me to ask for me to be sent out here to run his air show for him, I intended to do that very thing. I knew how to run an air force as well or better than anyone else and, while there were undoubtedly a lot of things wrong with his show, I intended to correct them and do a real job. I realized that so far the Air Force had not accomplished much but said that, from now on, they would produce results. As far as the business of loyalty was concerned, I added that, while I had been in hot water in the Army on numerous occasions, there had never been any question of my loyalty to the one I was working for. I would be loyal to him and I would demand of everyone under me that they be loyal, too. If at any time this could not be maintained, I would come and tell him so and at that time I would be packed up and ready for the orders sending me back home.

The general listened without a change of expression on his face. The eyes, however, had lost the angry look that they had had while he was talking. They had become shrewd, calculating, analyzing, appraising. He walked toward me and put his arm around my shoulder. "George," he said, "I think we are going to get along together all right."

I knew then that we would. I had been talking with a big man and I have never known a truly big man that I couldn't get along with.

We sat down and chatted for over an hour. I told him that General Marshall, Admiral King, and Harry Hopkins had gone to England to discuss with the British some operations to take the pressure off the Russians and that the next move would be to go into North Africa. He thought it a mistake and a poor gamble. If the Germans should move into Spain, Gibraltar would fall, closing the Mediterranean, and German aircraft operating from Spanish bases would wreck the whole show. Even if the Germans did not move into Spain, the results to be obtained by fighting our way east along the Mediterranean coast would not be worth the effort. It would be far better to land in France just as soon as the necessary force were built up and the proper degree of air superiority attained. Landing in Africa would not shorten the war anywhere near as quickly as landing on the European continent. Actually, by landing in Africa, our forces would be dissipated and the eventual landing in Europe thereby delayed.

As far as taking the pressure off Russia was concerned, he did not share the prevalent view that Germany was about to knock them out of the war. He said that, while the German was a better soldier than the Russian, Hitler was overextending himself without adequate rail and road communications and it had already been demonstrated that in winter the German offense could not move and even trying to hold their positions was bleeding them white. There weren't enough Germans to keep this process going forever, especially against the almost inexhaustible manpower reserves of Russia. Hitler was trying to conquer too much geography and in the long run the Germans would exhaust themselves.

The General told me that on the 7th of August, the South Pacific forces were to land at Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. The First Marine Division was to make the landing, supported by the available fleet units. He had been called upon to furnish naval and air support of the show and had already turned over a cruiser and a couple of destroyers from the naval forces under him which were commanded by Admiral Leary. He wanted to know what my recommendations were for the use of the Air Force. I told him that I didn't have any as I didn't know what there was to work with, but I intended to fly to New Guinea that night, look the show over there, and visit the airdromes in the Townsville area on the way back to Brisbane about the 2nd of August. I said we would do everything possible to help him carry out his commitments, but that I would prefer to tell him what that "possible" was when I got back. General MacArthur agreed and said, "As soon as you get back, come in and see me and we'll have another talk." We shook hands and I left.

MacArthur looked a little tired, drawn, and nervous. Physically he was in excellent shape for a man of sixty-three. He had a little less hair than when I last saw him six years ago, but it was all black. He still had the same trim figure and took the same long graceful strides when he walked. His eyes were keen and you sensed that that wise old brain of his was working all the time.

He wanted to get going but he hadn't anything to go with. He felt that Washington had let him down and he was afraid that they would continue to do so. He had two American infantry divisions, the 32nd and the 41st, but they still needed training. The Australian militia troops up in New Guinea were having a tough time and they were not considered first class combat troops, anyhow. The 7th Australian Division was back from the Middle East and they were about the only veteran trained fighting unit that the General could figure on for immediate action. His naval force, a mixed Australian and American show, was small and he had no amphibious equipment and little hope of getting any for a long time. All that could be spared was going to the South Pacific effort in the Solomons. The amount of transport shipping was barely sufficient to supply the existing garrisons in New Guinea. his Allied Air Force of Australian and American squadrons was not only small but what there was had not impressed him very favorably to date. No wonder he looked a little depressed.

I went back downstairs to see Brett. He took me around to meet all the Allied Air staff and tried to explain the organization to me. This directorate system of his, with about a dozen people issuing orders in the commander's name, was too complicated for me. I decided to see how it worked first, but I was afraid I was not smart enough to figure it out. Furthermore, it looked to me as though there were too many people in the headquarters. I thought I'd better see what could be done to cut down on the overhead and plow those people back into the combat squadrons.

In order to make it a truly Allied organization, the Americans and the Australians were thoroughly mixed everywhere, not only in the staffs but even in the airplane crews. An Australian pilot on a bomber, for example, might have an American co-pilot, an Australian bombardier, an American navigator, and a mixed collection of machine-gunners. It sounded screwy but maybe it was working. That was another thing I'd have to find out about.

The Swoose, the only surviving

B-17 at Clark Field, is now at the Smithsonian Institute. It was a mix of B17C & D parts – being

half swan and half goose it became the Swoose. The plane originally flown by H.

Godman was converted to the Swoose use of center design by H M S Smith and

became Gen Brett’s “Good Will” airplane flown by F. Kurtz below.

Cpl A. Fox, 1st

Lt M. MacAdams (co-pilot), 1st Lt H. Schriber (navigator), Capt F.

Kurtz (pilot), Sgt R. Boone, T/Sgt C. Reeves.

Air Vice-Marshal Bostock of the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) was Brett's Chief of Staff of the Allied Air Forces. He looked gruff and tough and was very anti-GHQ, like all the air crowd I'd talked to so far, but he impressed me as being honest and I believed that, if he would work with me at all, he would be loyal to me. A big, red-faced, jolly Group Captain Waiters of the RAAF was Director of Operations, and Air Commodore Hewitt, also RAAF, was Director of Intelligence. Both had several American officers as assistants.

Only an advanced echelon of the American part of Brett's air organization was in Brisbane. The rear echelon was still back on the south coast of Australia, 800 miles away, at Melbourne, under Major General Rush B. Lincoln. It was just as if the headquarters were trying to function at Chicago with its rear echelon in New Orleans, except that we would have had much better telephone service. All personnel orders were issued through Melbourne, the personnel and supply records were all down there, and, as far as I could learn, the boys were really bedded down to stay. That would be another thing for me to look into.

Brett told me of his troubles with Sutherland. They just didn't get along. Brett said he had so much trouble getting past Sutherland to see MacArthur that he hadn't seen the General for weeks and he just talked to Sutherland on the telephone when he had to.

Brett said it would take him several days to pack up and that he expected to leave about the 3rd of August. I told him I was going up to Port Moresby that night to look things over and he said to take his airplane, an old B-17 which had been named "The Swoose." The Swoose was supposed to be half swan and half goose; the plane had been patched and rebuilt from pieces of other wrecked B-17s.

I asked about Brigadier Generals Walker and Whitehead. Brett said he had sent both of them to Darwin to look things over there and become familiar with the situation in North west Australia and that he had intended to have them do similar tours in Townsville and New Guinea before bringing them back into his own headquarters. He said he though Whitehead had returned to Townsville, so I asked him to have "Whitey" meet me there and accompany me to New Guinea. Brett said he would send a wire to Major General Ralph Royce, the Northeast Area commander at Townsville, to that effect and have Royce go to New Guinea with me to show me around.

I took off for Townsville at eleven o'clock that night. Four hours later we landed, picked up Royce and Whitehead and an Australian civilian named Robinson, who, according to Royce, owned a piece of everything in the country and, as a leading industrialist, had a big drag with the government.

On the way to New Guinea over the 700-mile stretch of the Coral Sea between Townsville, Australia, and Port Moresby, New Guinea, Robinson spoke of knowing President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill and I gathered that he acted as a sort of unofficial ambassador for the Premier, Mr. Curtin. He had been quite helpful to Brett and was quite pro-American. He gave you the impression that he was a big shot and I believed that he was. He asked me to look him up in Melbourne and to call on him for help any time I needed it. I decided I'd remember him. I would probably need all the help I could get from any source before I got through with this job.

Soon after daybreak I got my first sight of New Guinea. The dark, forbidding mountain mass of the backbone of the country, the Owen Stanley range, rising sharply from a few miles back of the coastline to nearly twelve thousand feet and covered with rain-forest jungle was truly awe-inspiring. You didn't have to read about it to know that here was raw, primitive, wild, unexplored territory.

We picked up the now familiar line of coral reefs offshore, crossed the two-mile-wide calm lagoon, and flew over the beautiful little harbor of Port Moresby with the town and wharves on one side and perhaps a hundred native huts on stilts bordering the water's edge on the other. A few flat areas along river courses could be seen to the north and east of the harbor, where the bulldozers were at work raising huge clouds of dust but the general impression was that even the foothills of the Owen Stanleys that rimmed the harbor and separated the landing areas were rough and rugged. I figured that living in New Guinea would be like that, too.

About seven in the morning we landed at Seven Mile strip, just north of the town of Port Moresby. The airplane immediately took off for Horn Island on the northeast tip of Australia, in order to be out of danger from the daily morning Jap air attacks coming from Lae, Salamaua, and Band on the north coast, where the Nips had air bases. Seven Mile strip was used only as an advanced refueling point for the Australian-based bombers. It was defended by some Australian antiaircraft artillery and by the American 35th Fighter Group, equipped with P-39s.

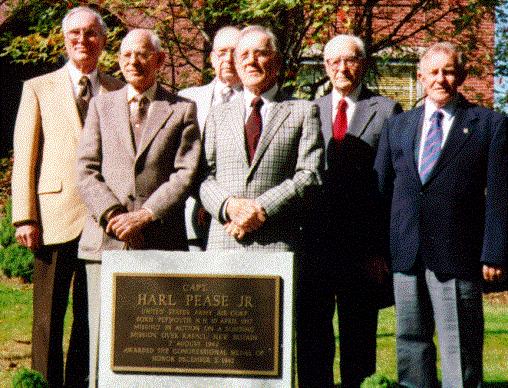

B/Gen Scanlon, second from right, gets a first-hand report from Lieut. R. W. Elliott on what happened .

Brigadier General "Mike" Scanlon, who was in command of the Air Forces in New Guinea, met us and accompanied us on an inspection of the camps and the construction of several other fields in the area. I had known Mike ever since 1918 and liked him immensely, but he was miscast in this job. He had been an air attaché in Rome and London for the best part of the last ten years, with a tour as intelligence officer in Washington. I don't know why they sent him up to New Guinea; he was not an operator and everyone from the kids on up knew it.

The set-up was really chaotic. Missions were assigned by the Director of Bombardment at Brisbane; Royce at Townsville passed the word to the 19th Bombardment Group at Mareeba, which was a couple of hundred miles north of Townsville; and the 19th Group sent the number of airplanes it had in commission to Port Moresby, where they were refueled, given their final "briefing" on weather conditions along the route to the target and whatever data had been picked up by air reconnaissance. The fighter group at Port Moresby sat around waiting for the Japs to come over and tried to get off the ground in time to intercept them, which they seldom did, as the warning service rarely gave the fighters over five minutes' notice that the Nip planes were on the way. Scanlon had the authority to use any aircraft in New Guinea in an emergency, if targets of opportunity such as Jap shipping came within range, and this authority had to be exercised occasionally when the bombardment planes arrived without knowing exactly what they were supposed to do.

The briefing was done entirely by Australian personnel. The system did not contemplate utilizing the squadron or group organization but dispatched whatever number of airplanes was able to get off the ground. No one seemed to be designated as formation leader and even the matter of assembly of individual planes was ignored. The aircraft might or might not get together on the way to the target. On the average, seven to nine bombers usually came up from Australia. Six would probably get off on the raid. The take-off generally took about one hour until they had all cleared the airdrome and usually within another hour two would be back on account of motor trouble. Others came back later on account of engine trouble or weather conditions, so that from one to three usually arrived at the target. If enemy airplanes were seen along the route, however, all bombs and auxiliary fuel were immediately jettisoned and the mission abandoned. The personnel was obsessed with the idea that a single bullet would detonate the bombs and blow up the whole works. The bombs, of course, were not that sensitive but no one had explained it to the kids, so they didn't know any better.

The weather service was not even sketchy. Weather fore casts were prepared by the Australian weather section at Port Moresby from charts of preceding years which purported to show what would happen this year. During July, the youngsters told me, three quarters of all bomber missions had been abandoned on account of weather. We could have done better than that by tossing a coin to see whether to go or not.

During the morning I attended a briefing down at Seven Mile Airdrome. The target was listed as Rabaul, the main Jap base in New Britain. Before the war Rabaul was a town of about 15,000. It had an excellent harbor and was defended by a heavy concentration of antiaircraft guns and two airdromes at Lakunai and Vunakanau. No particular point was assigned as target and I found out afterward that nobody expected airplanes to get that far anyhow, but, if they did, the town itself was a good target and there were always vessels in the harbor and the two airdromes were also considered worth while. The Australian weather man, in giving the weather conditions along the route and the forecast, mentioned "rine" clouds. I heard one of the youngsters in the back of the room turn to his co-pilot and say, "What are rine clouds?" The co-pilot answered, "I think he said `rime.' Probably the kind of clouds that have rime ice." The pilot remarked that he did not think that they had ice this close to the equator but then remembered that he had once picked up some ice at 20,000 feet over the Mojave Desert in California, and guessed that that was what the Australian weather man probably meant, after all. Several of the crews who overheard this conversation then became a little bit worried as they had no de-icing boots on their wings or fluid for the stinger rings to keep ice off of the propeller. I relieved their apprehensions by explaining to them that in the Australian accent "rain" became "rine.'

I then told Whitehead to see that in future an American staff officer was present at all briefings by the Australians and that as soon as I took over officially he was to form an American staff for operations in New Guinea and that this staff would be in charge of or at least supervise all briefings. Furthermore, that from then on we would have a definite primary, secondary, and tertiary target assigned for every mission.

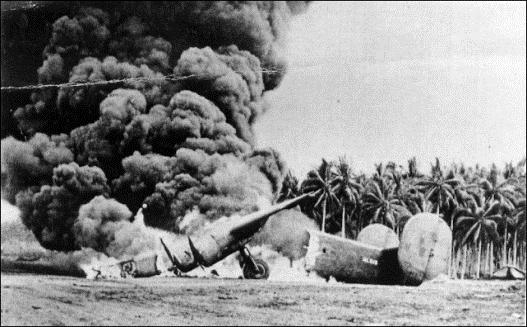

About noon the Japs raided Seven Mile with twelve bombers escorted by fifteen fighters which came in at twenty thousand feet and laid a string of bombs diagonally across one end of the runway and into the dispersal area where our fighters and a few A-24 dive bombers were parked. A couple of damaged P-39s didn't need any more work done on them, three A-24s were burned up, and a few drums of gasoline were set on fire, shooting up huge flames that probably encouraged the Jap pilots to go home and turn in their usual report of heavy damage to the place. A few other aircraft were holed but not seriously. Luckily the last of the five bombers that had come in from Mareeba at daybreak had left for a raid on Rabaul about ten minutes before the Japs arrived. One bomb hit on the end of the runway but that damage was repaired in about twenty minutes. I had a grandstand seat from a slit trench on the side of a small hill just off the edge of and overlooking Seven Mile, although I did not enjoy the spectacle as much as I might have under better conditions. The trench was full of muddy water and there were at least six too many people in with me.

There was no combat interception. The fighter-group commander seemed a bit proud of the fact that he had gotten ten P-39s off the ground before the Japs arrived overhead. With forty P-39s on the airdrome, I didn't think that was a very good percentage but I found that most of the rest were out of commission because they couldn't get engines, propellers, and spare parts up from Australia to replace stuff that had worn out or been shot up in action. Due to the lateness of the warning, which only gave four minutes' notice, the fighters, of course, could not climb to twenty thousand feet to engage the Jap bombers, which did their stuff and left for home without interference. Even the antiaircraft fire was ineffective. It looked, from where I was, short of the twenty-thousand-foot level and scattered all over the sky.

One thing was certain. No matter what I accomplished, it would be an improvement. It couldn't be much worse.

Throughout the whole area the camps were poorly laid out and the food situation was extremely bad. There was no mosquito-control discipline and the malaria and dysentery rates were so high that two months' duty in New Guinea was about all that the units could stand before they had to be relieved and sent back to Australia. Everyone spoke of losing fifteen to thirty pounds of weight during a two months' tour in Port Moresby. The piece de resistance for all meals, which was canned Australian M-and-V (meat-and-vegetable ) ration, was cooked, or rather heated, and served in the open as there was no mosquito screening anywhere. Swarms of flies competed with you for the food and, unless you kept one hand busy waving them off as you ate, you were liable to lose the contest. Even while walking around, the pests worked on you and it didn't take long to figure out what the kids meant when they referred to the constant movement of your hands in front of your face as "the New Guinea salute." Now, just throw in a continuous choking dust that seemed to hang in the hot, humid atmosphere and you began to realize that, in spite of the truly gorgeous mountain scenery and the heavenly blue of the ocean, it would be hard to sell the glamour of this part of the South Seas to the GIs. If you were thinking of dusky but fair sarong- or grass-skirt-clad girls, flitting among the palm trees, you were in for another shock. There were a few Papuan women in evidence around the native villages. They were dusky, in fact quite so, and they wore grass skirts, but from there on the dream faded. They forgot to give the poor girls any beauty to start with and the tattooing of tribal marks on their faces didn't help any. The prevalent mode of hair dressing called for the naturally fuzzy, kinky black hair to stand out from the head. This was accomplished by thoroughly applying pig grease, which got results apparent to the eye and, in the down-wind direction for a distance of at least a hundred yards, to the nose as well.

Both men and women worked around the camps building huts of bamboo framework thatched with palm leaves. The huts looked picturesque, kept out the rain, afforded shelter from the sun, and were nice things to stand in front of while you had your picture taken to send home to the folks, but after a short time they served as homes for a million varieties of spiders, scorpions, centipedes, lizards, and even birds. Luckily they were highly inflammable and accordingly, through accident or design, you didn't stay in the same house too long.

As New Guinea is close to the equator, darkness succeeded daylight with scarcely any twilight. You had just paused to ad mire the truly wonderful color display of the sunset, when blackness and the mosquitoes descended upon you. The mosquito problem was not being taken care of, with the result that the malaria rate was appalling. Most of the men had mosquito netting, but a large percentage of it was tom in places or full of holes and afforded little protection.

They really had mosquitoes up there. Big ones that dwarfed the famous New Jersey variety. I heard the usual yarn with a new locale when one of the kids tried to keep a straight face as he told me that one of them had landed over on the edge of the strip the other evening just after dark and the emergency crew had refueled it with twenty gallons of gasoline before they found out it wasn't a P-39.

The next morning I returned to Townsville with Royce and Robinson, the Australian "billionaire." I told Royce that he was going home as Arnold had a job for him running the First Air Force, which was a training show with headquarters at Mitchel Field in New York. He said he was glad to go and would like to have about ten days to straighten out his affairs and get packed up. I told Benn to make arrangements for space on a plane going back about August 10th. Royce said Walker was due in Townsville from a tour in Darwin, in a few days and asked whether or not I wanted him in Brisbane. I said that as soon as Royce left I wanted Walker to take charge in Townsville as head of a Bomber Command which I would organize as soon as I got back to my headquarters in Brisbaine. Whitehead would stay in Port Moresby, succeeding Scanlon. I asked Royce when Walker got in to show him the ropes and help him all he could before he left.

I decided to leave the Townsville show for Walker to straighten out. It turned out to be another scrambled outfit of Australians and Americans, with so many lines of responsibility, control, and coordination on the organizational chart Chat it resembled a can of worms as you looked at it. I made a note to tell Walker to take charge, tear up that chart, and have no one issue orders around there except himself. After he got things operating simply, quickly, and efficiently he could draw a new chart if he wanted to. The top Australian and Royce's Chief of Staff at Townsville was Air Commodore Lukis, a big likable individual who reminded me of Mike Scanlon. They even had the same kind of mustache. I didn't get much information out of him. In fact, the only one in Townsville who had the answers to very many of my questions was an Australian RAAF officer named Group Captain Goring. They called him "Bull," but he was active, intelligent, knew the theater, and had ideas about how to fight the Japs. He had flown and been all over the New Guinea country before the war and also knew New Britain, New Ireland, and the Admiralty Islands. I decided to keep my eye on him for future reference. I asked Goring about landing-field possibilities along the north coast of New Guinea between the eastern end of Milne Bay and Band where the Japs were. He told me that halfway between Milne Bay and Band, at a place called Wanigela Mission, there was a good natural landing field, approximately a mile long and half a mile wide, normally covered with the native grass called kunai which grew six to eight feet high. A few weeks previously an Australian Hudson reconnaissance plane had a forced landing there. The crew got the natives to cut a path through the grass and, after a second Hudson had flown up from Port Moresby and made repairs on the first airplane, both of them took off and returned home. This looked like something for me to investigate as a possibility for the future, the next time I went to New Guinea.

That afternoon I flew to Mareeba, where the 19th Bombardment Group equipped with B-17s was stationed, and talked with Colonel Carmichael, the group commander, and the youngsters. Carmichael had not had command very long but he seemed to have taken hold of the show and was trying. He had a real job on his hands and it was apparent that I would have to help him a lot. Walker would have to help, too. The 19th Group had been kicked out of the Philippines and out of Java and kicked around ever since. They had had innumerable group commanders who had come and gone without leaving anything behind them. The crews were thinking only of going home. Their morale was at a low ebb and they didn't care who knew it. The supply situation was appalling. Out of the thirty two B-17s at Mareeba, eighteen were out of commission for lack of engines and tail wheels. About half of them were old model B-17s, without the underneath ball turret to protect the airplane from attack from below, and in addition they were pretty well worn out. Anywhere else but this theater they would probably have been withdrawn from combat, but they were all we had so I'd have to use them if we wanted to keep the war going. Airplanes were continually being robbed to get parts to keep others running. At that moment the group could not have put over four airplanes in the air if called on for immediate action. Requisitions for supplies and spare parts were submitted by the group through Royce's headquarters at Townsville to an advanced air depot at Charters Towers, about sixty miles south of Townsville. Charters Towers, for some reason, sent the requisitions to Melbourne. Melbourne forwarded them to Tocumwal, the main Air Force depot about one hundred miles north of Melbourne. An average time of one month elapsed from the time the requisition started until it was returned, generally with the notation "Not available" or "Improperly filled out."

I said I didn't believe it, but the kids made me eat my words when they showed me a whole filing case of returned requisition forms. I took along a handful for future reference and as evidence that some of the people in the organization were playing on the wrong team.

I told Carmichael to cancel all flying and put his airplanes in commission for a maximum effort about a week later. I said I'd be back in a few days to talk things over with him again. I got a list of all the bits and pieces he needed to put his airplanes in shape, called Royce and told him not to schedule anything except the usual reconnaissance, and pushed off for Brisbane. It looked as though I'd have to start at Melbourne to get any thing moving. I decided to postpone bothering the Townsville Charters Towers supply organization until I came back in a couple of days to brief Carmichael and see what I could do to fire those kids up a bit. Carmichael told me that no one had received any decorations for months and then just one or two had been passed out. He was told to prepare recommendations for every deserving case in the group and that I would see that they got them promptly. I knew that little bits of pretty ribbon had helped in World War I; maybe they would help in this one, too. Anyhow, it wouldn't hurt to try. The next morning at the office I got General Lincoln on the phone and read him a list of things to ship to Carmichael at once. I told him not to worry about the paper work but to load the stuff in every air plane he had and fly it to Mareeba without consulting Towns Charters Towers, or anybody. Also that I would be in Mareeba in a day or two myself and would check up on deliveries and, if I found that he had delayed for any reason, I would demote a lot of people and send them home on the slowest freight boat I could find. I told him to call me back as soon as he had seen his supply people, report what action he had taken and what the schedule of departures from Melbourne and Tocumwal looked like. A colonel named Frye, who was running a small air depot in Brisbane, came in and I told him to report what requisitions from my list he had in stock and also to give me a forecast right away on how many B-17s then undergoing repair and overhaul at Amberley Field and Eagle Farms, two airdromes a few miles out of Brisbane, would be ready that day, the next day, and each day for the rest of the week.

Brett came in and asked me if I had any objection to his taking the Swoose, his private B-17, for the trip home as far as Hawaii, as it was hard to get air transportation that far by air. I said, "No." He also said that he would like to take Brigadier General Perrin back with him to Washington on temporary duty to help him compile his reports. I said okay, he could have him. I knew Perrin and didn't know what I could use him for. After Brett left, I'd wire Arnold to give Perrin a job in the United States.

I checked in with General MacArthur and talked with him for about two hours. I told him frankly what I thought was wrong with the Air Force set-up in both Australia and New Guinea and discussed the corrective action that I intended to take immediately. I asked him to give me authority to send home anyone that I thought was deadwood. He said, "Go ahead. You have my enthusiastic approval." I then discussed the air situation and told him that I wanted to carry out one primary mission, which was to take out the Jap air strength until we owned the air over New Guinea. That there was no use talking about playing across the street until we got the Nips off of our front lawn. In the meantime, our reconnaissance aircraft would be constantly looking for Jap shipping that should be hit at every feasible opportunity, but we were not going to get anywhere until we had won the air battle. I told him I had called off flying all bombers, B-17s, B-25s, and B-26s, until we could get enough of them in shape to put on a real show; that about August 6, just prior to the coming South Pacific operation to capture Guadalcanal and Tulagi, I would send the maximum number of B-17s against the main Japanese airdrome at Vunakanau, just southeast of Rabaul. The Jap aircraft there would raise the devil with the Navy landing operations if they were not taken out. At the same time, the B-25s and B-26s with fighter escort should be given a mission to clean up the Jap airdromes at Band, Salamaua, and Lae. The effort against the New Guinea airdromes should be continuous until the Jap airpower in New Guinea was destroyed and the runways so badly damaged that they even stopped filling up the holes. In the meantime, I would put everything else in support of the Australian drive along the Kokoda trail. General MacArthur approved this program and said to go ahead, that I had carte blanche to do anything that I wanted to. He said he didn't care how my gang was handled, how they looked, how they dressed, how they behaved, or what they did do, as long as they would fight, shoot down Japs, and put bombs on the targets. When I told him that I hoped to put between sixteen and eighteen B-17s on Vunakanau, he remarked that it would be the heaviest single attack in the Pacific war up to that time. It did seem like a lot of bombers, although the Japs were making it look rather small with their formations of twenty-five to forty bombers with about the same number of escorting fighters whenever they raided us at Darwin.

Back in my office, I asked Brett how many airplanes the Allied Air Forces had in the theater. He said he didn't know but called in the Director of Operations, Group Captain Walters, and Waiters said that he would try to get the information for me right away.

Brigadier General Cart Connell, Lincoln's assistant at Melboume, called me to give a report on how things were moving. They had a few spare engines for the B-17s but only two of their cargo planes would carry them, so only four engines could be flown to Mareeba the next day unless I could send down the one cargo airplane in Brisbane which could carry engines. I told him I would start it south right away. Propellers, tail wheels, and other spares, enough to fix up 12 B-17s, would also leave Tocumwal the next day. I told Connell to keep on shipping the rest of the list I had given them as the war would not stop after this operation. He wanted to know if he couldn't come up to see me about supply matters but I said not until the 19th Group had all the parts necessary to fix up every air plane in Mareeba.

I drove out to Amberley Field and talked with the mixed repair outfit, composed of Australian Air Force mechanics, American Air Force mechanics, and Australian civilians. I told them I wanted the place to operate twenty-four hours a day to finish up the five B-17s in work there. After a few pep talks and some arguments, I got a promise that four of them would be ready by the afternoon of the 5th.

In the evening I invited Benn and several of the lieutenant colonels and majors from Air Headquarters in Brisbane to eat, drink, and talk at Flat 13 at Lennon's. There were a couple of them, named Freddy Smith and Gene Beebe, who looked pretty good. They hadn't been in Australia very long and were anxious to work but didn't seem to be able to find out just what part they were to play in the war. So far they had spent most of their time shuffling papers from one directorate's office to another. There was a Lieutenant Colonel Bill Hipps who seemed to have a lot on the ball, too, but he was a Java veteran and a little tired. He did not say anything about going home but I figured I would use him for a few months and then send him back to the United States for a rest. I decided to clean out all the Philippine and Java veterans as far as possible. Most of them were so tired that they had almost lost interest. If we were to salvage them, they would need a long rest back home. I learned a lot from talking with those kids. Under the existing organization, so many people were putting out instructions, with or without the knowledge of the Commanding General, that no one could tell what the score was. The organization for getting supplies moving around the various gauges of the Australian railroad system and moving them up to the two fronts at Darwin and New Guinea was evidently so complicated that nothing moved. The whole service of supply was centered at Melbourne, which was 2500 miles away from the war in New Guinea. Even orders of the American part of the Allied Air Forces had to be issued from the rear echelon at Melbourne presided over by Major General Rush B. Lincoln. Most of the business was done by mail, although the telephone service was fairly good. The communication between Brisbane and Darwin was mostly by radio, as there was no telephone line between those two points. Communications to New Guinea were telephoned or mailed to Townsville and from there radioed or flown or sent on a boat across the Coral Sea to Port Moresby. The tendency seemed to be to keep every thing in the south on account of the probability that the Japanese would soon seize Darwin and land on the east coast of Australia somewhere between Brisbane and Horn Island. There was a lot of talk about the Brisbane line of defense, which was about twenty-five miles south of the city and upon which the Australians were supposed to rely for the last-ditch defense of Sydney and the country to the south. Everyone seemed to speak of the coming evacuation of New Guinea as a fairly good possibility. The organization was too complicated for me. I decided I would have to simplify it at least to the point where I could understand it myself.

Those youngsters following topside lead seemed to have an intense dislike of GHQ and all American ground organization. Sutherland was definitely unpopular with them. They said that he was dictating practically every action of the Air Force by his instructions to Brett. I told them to lay off the hate campaign. That MacArthur was okay, that he intended to let the Air Force run itself, carrying out general overall missions that he, of course, would approve. I also told them to quit wasting their time worrying about Sutherland, that I would take care of that situation myself, and that I would handle our dealings with the rest of the GHQ organization as well. These lads all wanted to work and I believed they could work. All they needed was somebody to lead them and we wouldn't have to get out of New Guinea or fight along the Brisbane line. However, someone had to go to work and it looked as though the finger were pointing at me.

Officially, Brett remained the Allied Air Force commander for the Southwest Pacific Area until he left for the United States. General MacArthur told me that for the present he was not going to release to the press the fact that I was even in the theater, as he didn't want the Japs to know that he was shaking up his command. However, Brett had already stopped issuing any orders and was helping all he could to get me acquainted with things before he left.

At noon each day, the commanders and top staff officers of the Air Force, the Navy, and the Australian Land Forces, together with a few representatives of GHQ, gathered in the Brisbane Air Force War Room, which was operated by the Air Force Directorate of Intelligence. There we were given the latest information from the combat zones, an analysis of enemy land, sea, and air strengths, locations of units and movements, with an estimate of probable hostile intentions. The briefing was done by reference to a huge map, about twenty feet square; of the whole Pacific theater from China to Hawaii on which colored markers and miniature airplanes and ships were correctly spotted to represent our own and enemy forces. The map was laid out on the floor in front of and a few feet below a raised platform on which we sat. The whole thing was very well done and served to keep us up to date on what was going on in our own and in adjoining theaters. Another valuable feature was that each day the heads and top staff officers of the three services saw each other and had a chance for brief discussion of the common problem: What were we all going to do about defeating the Japs?

General Sir Thomas Blarney, the Australian Land Force commander, took his seat regularly at the daily briefing. He was a short, ruddy-faced, heavy-set man with a good-natured friendly smile and a world of self-confidence. No matter what happened, I didn't believe Blarney would ever get panicky. He appealed to me as a rather solid citizen and a good rock to cling to in time of trouble. He was one of the few people I'd talked to outside of General MacArthur who really believed that we would hold New Guinea.

There was a Major General George Vasey who came in with Blamey that I liked the looks of. He was more like the Australian that we generally visualize, tall, thin, keen-eyed, almost hawk-faced. He was going to New Guinea soon to command the 7th Australian Division in combat and I thought we would hear a lot of him before this war was over. They told me his record with the 7th in the Middle East was excellent.

Vice-Admiral Herbert F. Leary, the Allied Naval commander, was another regular attendant. I'd never met him be fore but he was extremely cordial to me. There was some conflict between Leary and GHQ, but I had enough troubles of my own, so I didn't try to find out anything more. I gathered, however, that a successor to Leary would be on his way out here shortly.

The Australians seemed a little more than worried about being pushed aside by the Americans as soon as our forces and equipment would arrive in sufficient quantities to start offensive action. They are a young, proud, and strongly nationalistic people. So far, they had done most of the fighting in this theater and they wanted to be sure that their place in the sun was going to be recognized. I couldn't blame them and I promptly assured all the RAAF crowd that I was not going to be pro anything but Air Force and that I would fight to get airplanes, engines, and spare parts for both the Americans and the Aussies. I wanted aviators, regardless of nationality, who could fly, shoot down Japs, and sink Jap ships.

On the afternoon of the 3rd, Brett told me he was leaving the next day and then went upstairs to say good-bye to General MacArthur. He told me this would make the eighth time he had seen MacArthur since he had arrived in Australia last March.

Later he said the General had been extremely nice to him, had wished him all kinds of luck, and had presented him with the Silver Star Medal.

In the evening I went out to Brett's house where he was giving a farewell cocktail party. The house, called "Braelands," was one of the best in Brisbane. I understood that Robinson had secured it for Brett.

Misc photos from C Marvel, no names on photos.

At the party were all the top rank of both the American and Australian forces, lands sea, and air, and a few representatives of General Headquarters. I spent most of the time talking to Sir Thomas Blarney. I discussed the question of Wanigela Mission as a landing-field possibility and asked Blarney if he would let me fly some of his troops in there to occupy it while we built an airdrome. He did not offer any objection but said that he would give us Band in a few weeks. He stated that he intended to reinforce his force on the Kokoda trail, send a really aggressive commander up there, and order the Australians to advance, capture Band, and drive the Japs out of Papua. The Australians had just withdrawn to the Kokoda Pass in the Owen Stanley Mountains and expected to hold there until reinforcements arrived. Blarney seemed a little overconfident of the ability of his troops to make the trip over that extremely difficult, alternately mountainous and swampy trail through the rain forests from Port Moresby to Kokoda and still have enough drive left in them to chase the Japs out of the territory between there and Band itself. I didn't say so to General Blarney but I hoped that his confidence could be transmitted to his troops. From what I had been told in Port Moresby, those men up on the trail were worn out and it wasn't going to take much effort on the part of the Japs to crack the defenses of the Kokoda Pass.

On August 4th at daybreak, General George Brett left for Hawaii in The Swoose, Major Frank Kurtz piloting, taking Brigadier General Perrin with him, and I officially took over the job of Allied Air Force Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area.

Air reconnaissance at daybreak that morning showed a Jap concentration of approximately 150 aircraft, mostly bombers, on Vunakanau airdrome and over fifty fighter planes at Lakunai. The strength at Vunakanau was an increase of nearly 100 aircraft in the past two days. It might be an accident or it might be that the Japs suspected we were up to something in the Solomons.

I went up to Gen MacArthur's office, gave him the information, and told him that I still intended to attack Vunakanau with the maximum possible B-17 strength on the morning of the 7th as I believed there was a possibility that the Japs had read the Navy's mail and that this might be the reason for the recent heavy air reinforcement in the Rabaul area. I said I would like to strike earlier but the airplanes had to leave Australia on the 6th in order to refuel and take off from Port Moresby early on the morning of the 7th. In spite of the fact that the crews had been working day and night to get the planes in commission, if I backed up the schedule one day it would mean the difference between a decent-sized attack and one of four or five planes. The General agreed and again asked me how many B-17s I expected would take part in the raid. I told him I hoped that twenty would leave Mareeba and Townsville for Port Moresby on the 6th and I saw no reason why my original estimate of sixteen to eighteen over the target would not hold. He was very enthusiastic and wanted to know who was going to lead the show. I told him that I expected my group commanders to lead their groups in combat and that Colonel Carmichael was the group commander. He nodded approval and remarked that, if the operation went as I expected, it would be our heaviest bomber concentration flown so far in the Pacific war. He said not to forget to award as many decorations as I thought fit. He gave me authority to award all decorations except the Distinguished Service Cross, which he wanted to present himself as that was the highest decoration he was allowed to give. However, if a particularly deserving case came up and I wanted to decorate someone on the spot, he told me to just go ahead and he would confirm it.

During the afternoon, orders came down from GHQ covering our support of the South Pacific Guadalcanal operation. Instead of ordering the Allied Air Force to support the show by a maximum effort against the Jap airdromes in the Rabaul area and putting in the usual sentence about "maintaining reconnaissance," the order went into a page and a half of details prescribing the numbers and types of aircraft, designating units, giving times of take-off, sizes of bombs, and all the other things that the Air Force orders are supposed to take care of.

I immediately went up to see Sutherland and had a show down with him on the matter. I told him that I was running the Air Force because I was the most competent airman in the Pacific and that, if that statement was not true, I recommended that he find somebody that was more competent and put him in charge. I wanted those orders rescinded and from that time on I expected GHQ would simply give me the mission and leave it to me to cover the technical and tactical details in my own orders to my own subordinate units. When Sutherland seemed to be getting a little antagonistic, I said, "Let's go in the next room, see General MacArthur, and get this thing straight. I want to find out who is supposed to run this Air Force."

Sutherland immediately calmed down and rescinded the orders that I had objected to. His alibi was that so far he had never been able to get the Air Force to write any orders so that he, Sutherland, had been forced to do it himself. I asked him if he prescribed for the Navy what their cruising speed should be and what guns they would fire if they got into an engagement. He didn't say anything. No wonder things hadn't been running so smoothly.

I spent the rest of the afternoon working out a reorganization of the Air Force. I decided to separate the Americans and the Australians and form the Americans into a numbered Air Force of their own which I would command, in addition to commanding the Allied show. The Australians would be organized into a command of their own and I'd put Bostock at the head of it. My Allied Air Force headquarters would remain a mixed organization. I would not only command it, but be my own chief of staff until I could get someone from the United States to take over. To keep the Australians in the picture I would leave Group Captain Waiters in as Director of Operations and Air Commodore Hewitt as Director of Intelligence for the Allied Air Force headquarters. As American assistants, Lieutenant Colonel Beebe would work with Waiters and a Major Benjamin Cain would be Hewitt's assistant director. Besides letting the Australians have something to say about the show, I really hadn't an American capable of doing either of these jobs unless I took Walker or Whitehead out of the combat end. I couldn't afford to do that.

It was quite noticeable in New Guinea and up at Mareeba that the combat units were short-handed. Back in Brisbane it was equally noticeable that officers were falling all over them selves. I decided to have a real housecleaning right away. Those who were not pulling their weight could go home and the rest would move north to take their turns eating canned food and living in grass huts on the edge of the jungle. Furthermore, there were a lot of those kids up in New Guinea who ought to come back to Australia for a couple of weeks rest. Many of them told me that they had been in combat continuously for four or five months.

The next morning I flew to Mareeba, assembled Carmichael and his squadron commanders, and gave them instructions for the raid on Rabaul. The primary target was to be Vunakanau, the secondary target Lakunai, with the shipping in Rabaul Harbor on third priority. It looked as though twenty bombers would take off the next morning for Port Moresby. The group was quite elated over the fact that they were to finally put on a big show. I cautioned Carmichael and the squadron commanders about holding formation, as they would undoubtedly run into plenty of Jap fighters. They were a bit concerned about their formation work as they were not used to flying "in such large numbers together." I couldn't help but shudder at this evidence of a lack of formation training when twenty airplanes appealed to the kids as a large formation. I told them that from now on we would utilize every opportunity to practice formation flying as well as quicker take-offs and assemblies in the air. I said that the exhibition I had seen at Port Moresby of six B-17s taking an hour to get off the ground and never assembling into formation before arrival at the target was something that I did not want to see again. I gave them a long talk on the subject of what would happen to a bomb if it were hit by a machine-gun bullet. Hundreds of tests had shown that the bomb would not blow up as the crews believed, so there was no excuse for unloading the bombs just because an enemy airplane headed in their direction. From that time on, we wanted the bombs put on the target. They seemed glad to get the information which relieved them of one of their biggest worries.

***

The Charters Towers air depot was not paying its way. It bad a lot of hard-working earnest kids, officers and enlisted men, who were doing the best they could under poor living and eating conditions, but their hands were tied by the colonel in command whose passion for paper work effectually stopped the issuing of supplies and the functioning of the place as an air depot should. He had firmly embedded in his mind the idea that he could not issue supplies if he was taking inventory or if the requisition forms were not made out correctly. Requisitions coming in from New Guinea and even from the 3rd Group on the other side of the field were repeatedly being returned because notations were made on the wrong line or the depot was too busy sorting out articles that had just been shipped in. He told me that he thought "it was about time these combat units learned how to do their paper work properly." I decided that it would be a waste of time to fool with him so I told him to pack up to go home on the next plane back to the United States. The excuse would be "overwork and fatigue' through tropical service. I told Bill Benn to get his name and make arrangements by telephone with my office at Brisbane to ship him home. A good-looking major on the depot staff told me he knew what I wanted done. I put him in command and told him that beginning immediately I wanted all requisitions, verbal or written, filled at once regardless of the state of inventory or whether or not the forms were filled out properly and that whenever possible he was to fly the equipment or parts to points where they were needed in order to speed up maintenance and get airplanes back into commission.

The ingenuity of the kids at Charters Towers was an inspiration. In spite of canned Australian rations and hot, dirty, dry season living conditions in tents in bush country, they were trying. The junior officers were helping all they could. The seniors had been the stumbling block. There were very few spare instruments, so the kids salvaged them from wrecks and repaired them. There was no aluminum-sheet stock for repair of shot-up or damaged airplanes, so they beat flat the engine cowlings of wrecked fighter planes to make ribs for a B-17 or patch up holes in the wing of a B-25 where a Jap 20-mm shell had exploded. In the case of small bullet holes, they said they couldn't afford to waste their good "sheet stock" of flattened pieces of aluminum from the wrecks, so they were patching the little holes with scraps cut from tin cans. The salvage pile was their supply source for stock, instruments, spark plugs anything that could be used by any stretch of the imagination.

One youngster had built, out of scraps of junk, a set for testing electrical instruments. I asked him if he could assemble the stuff, which he had spread all over a table, into a box the size of a small suitcase and give me a drawing of it so I could send it back to the Air Force Materiel Division at Dayton and have it standardized as a field testing apparatus. He grinned all over and said he could and would. I told him after he finished that job to make about six more of them as it was the best thing of its kind I had ever seen and I wanted to put them around the other places where repair work was going on.

***

This youngster was M/Sgt Rua C. Hayes, 28th Sqd

BOMBSIGHT TEST PANELS

From a wrecked LB-30 the generator ammeter panel was salvaged, a few more instruments, a lot of different types of switches and a whole lot of wiring with the proper cannon plugs. These gave us a Bombsight Test Panel, which told us all we needed to know about the Bombsight and AFCE as a whole, or of any integral part, either in the shop or in the airplane.

This small test panel worked out so many troubles, was so handy with the Bombsight mechanics that it is aboard a ship being taken to the states to be presented to Wright Field with the suggestion that many similar test panels be made and shipped to various bombardment groups.

GENERATOR TEST SET

By taking an electric motor from an old unused hydraulic pump set, it was possible to make the work of testing electric equipment very easy.

A flexible mount was made for the generator and two pulleys were secured from wrecked car fans. With a V-type belt the motor was made to operate the generator at 2200 rpm.